VIDEO OF THE LAST CHANCE TORNADO!

Supplemental Info on this chase!

Note: I wrote a couple of versions of The Last Chance Chase shortly after this chase in July of 1993. The account that follows was written for the TESSA Weather Bulletin. Below it are some “notes and thoughts” regarding the event written more than 14 years later. And, at the bottom of this page, I have pasted the account which appeared in the Stormtrack newsletter in the winter of 1993.

THE LAST CHANCE CHASE

by William T. Reid

An ample number of tornados were reported this past spring and early summer, but associated weather conditions in tornado alley made catching, and then even seeing, a tornado a very difficult task for most chasers. Persistence, patience, and good old-fashion luck allowed my chase partner and myself to buck the odds this tornado season, though. Consider the probability of the following: perhaps the most spectacular tornado-video footage of 1993 was taken by a Californian—in Eastern Colorado—in late July! The following is an account of a chase of a lifetime.

I spent much of the first two weeks of July 1993 in silent and envious frustration. It seemed that on nearly every afternoon a severe thunderstorm watch or tornado watch box was plastered over Eastern Colorado–and here I was in mostly-fair-weather land: the San Fernando Valley. I had driven twice to the Great Plains to storm-chase in May, and the most I had to show for that was some wall and funnel cloud activity. I was in numerous boxes and warning areas in May from Wyoming to Texas, but much of the storminess was excessively rainy, fast-moving, and along lines: definitely not conducive for catching tornados. Probably the highlight of the two trips was on May 29 in Ness City, Kansas. I became the happiest man in town as I watched my beloved Los Angeles Kings defeat the Toronto Maple Leafs in Game 7 of the Conference Finals!

A chase trip tentatively planned for the weekend of July 10-11 was stymied by last-minute work requirements, so I made plans for the following weekend, should the severe weather pattern over the High Plains continue. (A “weekend” trip for me typically lasts six days.) The favorable weather pattern did continue (I could tell because night and morning low clouds reigned throughout coastal Southern California–more like May weather than July), so Charles Bustamante and I headed for Eastern Colorado on Friday, July 16th. On each day from the 17th to the 20th we found ourselves amidst severe weather in Eastern Colorado, with brief excursions into Nebraska and Kansas. We saw small tornados and funnel clouds near Bennett and Punkin Center, plus towering supercells and fantastic lightning displays.

We awakened Wednesday morning, July 21, in Colorado Springs, quite satisfied with what we had seen so far. The Weather Channel indicated that Eastern Colorado was primed once again for severe weather that afternoon, and we were debating whether to stay and chase one more day or not (work was not in urgent need of us!) We definitely did not want to end up well into Kansas or Nebraska late that evening, which would have made the dreaded drive home that much longer.

Charlie and I stopped by the National Weather Service Office in Colorado Springs and met Jim Maxwell, who was very friendly and helpful. He checked the severe parameters for that afternoon and determined that northeast Colorado was much more vulnerable than southeast Colorado. Jim said that there was a quasi-dry line situation setting up east of Denver, with good moisture convergence in the area from Sterling to Akron.

After lunch we headed north to Denver, with the option in the backs of our minds of jumping onto Interstate 70 and heading home should nothing significant develop. Denver was hot and dry at 1 p.m.–91 degrees, 14% relative humidity, with light winds. At 1:30 p.m. Denver NOAA WeatherRadio issued a statement concerning a small thundershower which we could see to the east, near Deer Trail. I thought that those clouds hardly warranted a statement, but chasing is in our blood and we headed east! This would definitely be our final chase, our last chance for something special in 1993.

Near Byers, Colorado, we sat under a showery and electric cloud for about a half hour and observed a possible landspout (with barely a funnel) on the southern edge of the small storm. The thunderstorm gradually strengthened as it slowly moved east. It was only a few miles north of U.S. 36, and by remaining on or near U.S. 36, we were in excellent position to monitor for any tornadic activity, which typically occurs near the southwestern edge of storm cells.

This storm had a lot going for it. It was very isolated, so there was no competition with nearby cells for moisture and energy, and it was drifting into increasingly moist and unstable air over extreme Eastern Colorado. Moist, low-level, upslope, southeasterly winds fed the cell, and southwesterly upper-level winds and an approaching upper-level disturbance encouraged vertical development and rotation. Air Global Weather Central at Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska (in a backup capacity for the National Severe Storms Forecast Center in Kansas City) issued a tornado watch for most of the plains of Eastern Colorado at 4:37 p.m. MDT.

At 6 p.m. the storm was just north of Last Chance, Colorado. It had moved only 30 miles east in three hours! One could have chased this storm on foot, though he would have been a good target for lightning and dusty outflow winds.

Several attempts at decent wall cloud formation fizzled, but at 6:00 p.m. MDT, several dust whirls spiraled upward beneath the main updraft. At the same time, a clear slot associated with the rear-flank downdraft appeared. No funnel clouds had been seen yet–the dust whirls may have been gust-nados. Large hail was reported north of us, at Woodrow. Near Last Chance a couple of storm chasers and Sky-Warn spotters gathered, and a tornado warning was issued for southwest Washington County until 6:30 p.m.

Finally, a good-looking funnel cloud formed a few miles northeast of Last Chance, beneath a rotating updraft. It never appeared to touch the ground, but there were several other small and weak “dust-nados” underneath the grayish/white updraft. The chase party converged again along a dirt road a couple of miles north of Lindon at 7:20 p.m. We had three storms to watch now–the primary storm, slipping into darkness to the northeast; a nice bell-shaped-based updraft to the northwest, and a developing cell to our southwest.

Charlie and I left the others and headed a few miles north and east, somewhat undecided about where to go, but trying to keep the base of the original storm in sight. The other storm to the northwest was weakening, and the one northeast of us looked less organized. What surprised me at this point was that the low clouds above were streaming to the southwest–towards the newest updraft! We observed that the base of this storm, perhaps 15 miles away and back near Last Chance, was issuing some very suspicious shapes.

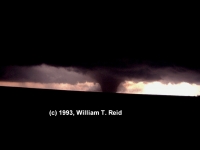

It was off to the races: south to U.S. 36, west a couple of miles to Road U (two miles east of Lindon), and south again five more miles. While we videotaped and zig-zagged ever closer to the storm, the obvious shape of a tornado gradually appeared. Anticipation, anxiety, and exhiliration reached new heights for Charlie and me–this was our first real tornado: it wasn’t a wimpy landspout or funnel-less dust whirl. For a few seconds two tornados were observed, side-by-side. We turned west off of Road U onto Road 7. A few miles, dead ahead, was a–dare I say–black monster, a huge tornadic wedge, maybe more than one-half mile wide–churning the farmland. We could not believe what we were seeing! We could not believe what Mother Nature was offering us!

Charlie and I were awestruck as we cautiously drove another mile west. We passed a farmhand who was working with some equipment by the road. I honked, as it appeared he had no idea of the impending calamity swirling a few miles away. At Road T a combination of fear and common sense came over us (this is close enough!), and we stopped to set up the tripods. It was 8:00 p.m.–still about 15 minutes before sunset. We both felt that we would not be able to linger long at this site. Though the tornado was not moving forward very quickly, we thought that we were in its path. We were contemplating escape routes: Road T, unfortunately, only went north–into an increasingly black and noisy thunderstorm, surely filled with hail. The car was left running and pointed east down Road 7.

Charlie’s camera clicked away and I monitored the camcorder as the tornado slowly approached. We had an excellent view: there was nothing to obscure this grand vision! Sunlit skies framed the black and ominous wedge as it decreased a little in size and moved slowly to the left from our perspective. After about six minutes the tornado was twice as close as when we had stopped, but we felt much less threatened, as it was now southwest of us and moving east-southeast. (We became more concerned with the nearby hollow-sounding crashes of thunder just to our north.)

An amazing sequence of events was about to transpire. The wide condensation funnel began to dissipate near the surface, so that the entire rotation (front and back) could be seen. Just when I thought that the tornado was going to end, a very thin condensation “needle” formed inside of the larger circulation. The needle rapidly expanded–and our large, black wedge had become a rather narrow, gray column. Less than a minute later the column’s bottom portion began to disappear, but another narrow tube quickly reformed. The tornado now had a more classic, slender-looking funnel shape. During the next couple of minutes the gray tornado again assumed a more-columnar shape; to our south-southwest it stood nearly stationary in “Tower-of-Pisa”-like formation.

About ten minutes after we had stopped to set up, the tornado rapidly roped-out for good, leaving behind a cloud of dust and two happy people. How fortunate could two storm-chasers be? We had just captured some of the most incredible tornado video ever! We were provided with a large, slow-moving tornado from a relatively tranquil, obstruction-free viewing site with great backlighting! Murphy’s Laws were not in force: all cameras worked, the car continued to run, and lightning lurked but did not strike us.

A farmer, Philip Scott, and his wife, Lois, drove up to us only a minute or so after the tornado vanished. Their home was the farm house one-quarter mile west. Mrs. Scott said that she had seen us along the road from the house and wondered if we were stuck or something. Then she looked west and fled for the basement! Her husband had watched the storm from another part of his farm. The Scott’s home was spared because of the “right-moving” tendency of tornadic storms. (We learned later that the tornado was four miles west of us when we set up, and two miles away when to our southwest. It touched down near Roads N and 7, and dissipated near Roads S and 4. It injured some animals and damaged some farm equipment on its six-mile trek.)

The supercell spawned another tornado around 8:30 p.m., which wrecked a farmstead. Charlie and I were content to watch the storm from the Scott’s place, and we did not see that tornado. I was concerned for our safety and the body of the car, as lightning increased and golfball-sized hail sprinkled our vicinity. The farmland beneath the rotating supercell’s incredibly low base, only a couple of miles to the southeast, was awash in a murky-white haze. Who knew how large the hail was underneath that behemoth? What senseless soul would dare test the fury of this airborne maelstrom? Well, we could see who–a Denver TV-NEWS crew!

I called Channel 4 in Denver, and we met their newsvan at Byers at 10 p.m. Our tornado video was seen on the Denver news that night. Charlie and I began the drive home. It was not until we reached Los Angeles the next evening, exhausted but still exhilirated, that we learned that our last chance chase–our Last Chance tornado–had been shown over and over again on The Weather Channel.

Some notes and thoughts on this event:

This was truly the storm chase of a lifetime for myself and my chase partner, Charlie. This was a “career chase”, meaning that it is doubtful that I would again experience something so special, so extraordinary, and so spectacular.

The first large “Last Chance” tornado was the wedge tornado which formed several miles southeast of Last Chance and roped out about seven miles south of Lindon. Despite its size and strength, it was rated F0, since it did not strike any structures and was virtually impossible to rate. Only rangeland and farmland were affected. The second tornado was witnessed by several chasers as dusk fell, and it was large and slow-moving. It wrecked a farmhouse and was rated F3.

More than 14 years later, I think about those ten minutes at Road T and Road 7 and I shake my head and smile in disbelief. Charlie and I had someone smiling down on us that day. I wasn’t looking to become a “name” chaser when I began chasing on the Plains in 1991, but my video of this event made my name known to every chaser. The funny part is that there was so much dumb luck involved which allowed us to wind up where we did when we did. If I had been able to chase earlier in the month, I would not have been in Colorado on July 21. Charlie could not escape work requirements around the weekend of July 10/11, so we chased a week later, beginning on July 17. Charlie and I almost started driving home midday on the 21st. If there had been no storm development before 3 or 4 p.m., we might have decided to begin the drive back to Los Angeles from Denver.

And, knowing what I know now about chasing, it is doubtful that I would have wound up at Roads 7 and T at 8 p.m. on July 21. I was not experienced around supercells in my third chase season. I knew some basic stuff —- where large hail was likely, where wall clouds and tornadoes might form beneath the updraft base, etc. I wasn’t very good at noticing, understanding, AND reacting to the clues that the atmosphere offered to chasers. I was learning on the job, a severe-weather novice from California. Keep in mind that in 1993 there was no Internet to help one learn about severe weather and tornadoes. I had read some Stormtrack chase accounts and articles and had watched a handful of chase videos. There were no training videos on chasing and severe storms, but Tim Marshall’s 1991 chase video helped me know my way around a supercell. I didn’t have any friends who had chase experience. I had only seen one or two supercells in my life prior to the Last Chance chase.

In 1993, chasers would make a forecast, drive to their target area, listen to NOAA wx-radio, and use their eyeballs and brains to figure out where they should be. Data updates via pay phones, the Weather Channel, or local television were sometimes available. However, on most of the Great Plains, on most chase days, it was just you and your eyes and your instincts to get you to the right spot. It was much, much easier to make poor decisions back then. It was frustratingly easy to botch a chase and to miss a great storm due to one ill-advised move, or thought, or delay. Compared to the real-time data available to the chaser today, chasing in 1993 was like chasing in the Dark Ages.

Part of the allure of chasing on the High Plains is that visibility is usually excellent, and the experienced chaser often doesn’t require a bunch of electronic goodies to figure out where he ought to be. On July 21, 1993, Charlie and I had an easy time of it along U.S. 36. The supercell was slow moving and was paralleling the highway. The action area was just to our north, and it was easy to be in great position should a tornado develop. For this event, it was the second supercell, which formed around 7:30 p.m., a little southwest of the original long-lived supercell, which became the big tornado producer. If I were chasing this event today, with the real-time data and radar, would I have managed to get good footage of the large tornadoes with the second supercell? Perhaps not. The critical decision-making time on this chase was between 7 p.m. and 7:30 p.m. If I had known how to chase and knew what I know now….I hate to think about what might have happened.

One move, or non-move, which saved Charlie and me from being way out of position, was by NOT staying close to the updraft base of the first supercell north of U.S. 36. We kind of allowed it to drift away to the northeast of us, even though it had classic structure, a clear slot, and some dusty spin-ups beneath the updraft base. There might have even been a decent-sized tornado with it as we watched north of Lindon with several other chasers. The video shows dust or condensation between the ground and the storm base, several miles to the ENE, around 7:20 p.m., and I wonder aloud whether a tornado is indeed in progress. Why weren’t we in position, east or southeast of the updraft base? Good question, and, in fact, chaser Jack Corso asked me this question years ago after he had watched my video! The answer—-“I don’t know”. I didn’t know what I was doing. Charlie and I were out of our league, for sure. The storm north of U.S. 36 didn’t seem to be getting better organized, however, and there were only dirt roads available to stay with it, unless we dropped a few miles back down south to U.S. 36 in order to blast east. The other chasers seemed undecided on what to do next, as there were three updrafts to consider, and we were in the middle. If I had live real-time radar and today’s chase experience on July 21, 1993, I very well may have been trying to stay close to the original updraft base as it moved ENE of Lindon. If I were positioning myself east or southeast of the updraft base, then it is likely that I would have been too far away to catch the first large Last Chance tornado. However, if I had noticed in time that the original supercell was going downhill while a new one was starting to crank to its southwest, then, given the chase experience I have today, I might have been able to recover in time.

As it happened, Charlie and I decided to try to stay “somewhat” close to the “Lindon” supercell after 7:25 p.m. or so by going north on Road S a few miles and then east to Road W. At this point in the chase, we were excited about the supercell we had chased this day, but we thought that things were winding down. It was difficult to see what the Lindon supercell was doing, in part due to a lot of low clouds. I noticed that the low clouds were streaming rapidly to the southwest, and this should have been a major clue that something very significant might have been developing to the southwest. We didn’t put two and two together. The low clouds did not allow a good view of what was happening to the southwest, south of U.S. 36. If we had been smart enough to head southwest to the Last Chance supercell at 7:30 p.m., then we would have been in great position to see the entire life-cycle of the first large tornado. But, would we have wound up in as good or better a place to watch the event? I doubt it. Tim Samaras was very close to the wedge tornado during its early stages. Tim was a little west of the wedge, and was battling wind and rain and poor contrast. If we had gotten to within a mile or two of the developing tornado, Charlie and I may have wound up with a fantastic show with great contrast north or northeast of the tornado for a while, but I think we would have been forced to move due to precipitation at some point during the tornado, and/or the contrast would have have deteriorated as the tornado moved to our southeast.

Yes, it was in large part just dumb luck that evening that got us to the right place at the right time. Charlie and I weren’t quite sure what to do as we stood outside the Pathfinder, eight miles or so northeast of Lindon around 7:40 p.m. The big show was developing about eight miles southwest of Lindon, but we didn’t know it. We noticed a marked increase in lightning with the new cell to our southwest, so we elected to head that direction. It was about 7:40 p.m., and twenty minutes later we were four miles east of the wedge tornado at Roads 7 and T.

As I think I alluded to and tried to make obvious in the original article above, Charlie and I were dumbstruck and awestruck as the Last Chance tornado evolved. We were absolutely floored and amazed. We were long-time photographers, too, so we went to work in a business-like manner to make sure that we didn’t mess up this opportunity. The tornado video that I shot wound up Number 8 on Tom Grazulis’ Tornado Video Classics collection several years later. (Tom said that the relative lack of enthusiastic audio, such as yelling and screaming, kept the ranking from being a little higher!) What makes this tornado video so special?

Even as late as the early 1990s, quality tornado video was rare. Camcorders were not commonplace, and they tended to be bulky, balky, expensive and/or rather poor in picture quality. Sony came out with a “Hi-8” model camcorder around 1990, and this was a huge step up in video quality over the consumer 8 mm and VHS camcorders. I purchased a Hi-8 in May of 1991, not long after watching some of the tornado video on the news from the outbreak on April 26, including the huge Andover tornado. I wanted to chase storms, I wanted to see tornadoes, and I wanted to get decent video and pictures of them. I plunked down $1500 for the Sony Hi-8, and it was one of the best investments that I ever made. So, a huge reason why the Last Chance tornado video was special and rare was because it was shot with a quality camcorder, and I managed to have it focused properly. I kept it steady on a tripod and didn’t zoom and pan too much. If you are an aspiring chaser, then I strongly recommend that you purchase the best cameras and lenses and camcorders that you can afford.

With a good camcorder in place, the rest was up to Mother Nature. Large, black wedge tornadoes are rare enough, and it is not easy to place oneself in a safe place which maximizes the viewing pleasure. Typically, good contrast is to be found only in a few select spots around a large tornado. Most often, the best contrast is in front of the tornado or a little north of it as it moves east. Charlie and I approached the storm from the northeast, and this allowed us to have excellent contrast for the tornado for the duration of the event. The supercell was so strong that it carried the bulk of its precipitation well to the east through northeast of the updraft base—basically well above our heads! Large hail is oftentimes a nuisance, a problem, or a significant threat to safety for chasers who put themselves in the path of supercell updrafts. We drove through some small hail near U.S. 36 and Road U as we made our way south to get east of the tornado, but otherwise had no precipitation issues. This was another case of good fortune. We were in a region relative to the storm which was highly vulnerable to large hail and/or rain. As we drove south and west, precipitation could have resulted in a different route or course of action, but it was negligible, fortunately (and miraculously).

Okay, we somehow wound up placing ourselves a few miles east of a large and slow-moving tornado, which was moving towards us, presumably. The spot is perfect. There are no trees and no buildings, save for a small house a quarter mile to the west. There is only gently rolling pastureland, a supercell and tornado, and bright sunlit skies behind the tornado. There weren’t even any telephone poles around. What can one expect in these situations? Certainly, one cannot expect to be able to stick around for very long. I was worried about large hail, but apparently that remained a ways to the north and northeast towards the forward flank precipitation core. I was worried about lightning. We were the highest objects around. There were some flashes towards the north, and some shotgun-like blasts of thunder overhead. The thunder sounded like it was trapped in a chamber, as I mention on the video. Lightning and thunder were not close enough to cause us to get back in the vehicle. Eventually, wind would make life difficult as the tornado approached, right? It didn’t. The tornado wound up going to our SSW, and wind speeds were 10-15 mph or less for the ten minutes when my camcorder was tripodded and shooting the tornado. It is almost unbelievable that I was able to set up a tripod where I did and leave it there for ten minutes without being hampered by precipitation, lightning, wind, dust, etc. This just does not happen, people!

I have detailed the videography and superb ambient weather conditions which prevailed at Roads 7 and T from 8:00 to 8:10 p.m. The stage was set, and the Last Chance tornado did not disappoint. It put on a show as it morphed from wedge stage to rope out, with a couple of tricks up its sleeve in between, all with fantastic contrast from our perspective. If the tornado had curved to the north instead of the south, then the contrast would have deteriorated and we may have had wrapping rain and hail to contend with. If it had continued due east, we likely would have had to get out of the way after 6-8 minutes to stay safe. The thing curved to the right and went to our southwest. Dumb luck strikes again. How many chaser tornado videos have you seen where the chaser is able to remain stationary and watch a wedge tornado evolve to rope out stage with excellent contrast throughout and without some weather nuisance?

I have seen dozens of good-sized tornadoes since July 21, 1993. None have come close to matching the magic that was Last Chance tornado. If the weather gods allow me another chance, will I be brave enough, or smart enough, or stupid enough, to place myself in a similar position? I don’t know. I know what I’m doing now.

Alternate version of the Last Chance Chase, written for Stormtrack Magazine, by William T. Reid:

Late last May I had the opportunity to read many of the early issues of Stormtrack. My friend and

fellow chaser, Charles Bustamante, had packed nearly a dozen volumes of Stormtrack for our latest excursion

to the Plains. Near Glendale, Nevada, I recall reading a fantasy article/cartoon by David Hoadley. The star in

this "Gentleman's Chase" wakes up somewhere in tornado alley, has a leisurely lunch, watches a storm develop

nearby, and photographs a tornado while in perfect position after a brief drive. For him, it was just another

typical chase day.

Charlie and I were making the long and arduous drive home to Los Angeles at the time. We had chased

for five days and had seen--maybe a gustnado, maybe a funnel cloud--but certainly no classic tornado. It was

my fifth return trip from the Plains in three years, and I was batting way under my weight, tornadically speaking.

I laughed to myself while becoming quite envious of Hoadley's fictitious character. How dare this individual

reap nature's reward without suffering hours, weeks, and years of frustration! As I strained to stay out of the

Nevada sun, I wondered when my chase efforts would pay off. It did not look like 1993 would be the year.

It certainly was not likely to be the way of this "Gentleman's Chase!"

Charlie and I were on the road again--in mid-July! We had the oppurtunity to stretch a weekend into

five or six days, so we threw the cameras into the Pathfinder and trucked through that great Great Basin trough

to the plains of Colorado. Ahhh, Eastern Colorado!--upslope flow, great CBs, fabulous shear, big hail!

Awesome storm photography! Tornadoes? Well, a debris-whirl here, a landspout there, here a funnel, there a

funnel... Well, Colorado tornados are weak.

Four days of successful severe-storm chasing and photography behind us, we awoke in Colorado Springs

and debated whether to head home or to stay and chase one more day. We definitely did not want to make that

dreaded drive home much longer than it already was, i.e., by ending up well into Kansas or Nebraska at the end

of the day (it was Wednesday, July 21, 1993). Jim Maxwell, NWS forecaster in Colorado Springs, informed

us late that morning that extreme northeastern Colorado could go severe that afternoon. We could deal with that!

Several severe weather parameters were forecast to combine from Eastern Montana to Northeast

Colorado. Surface low pressure along the front range was drawing moist, low-level air from the east and

southeast into Northeast Colorado. A dryline situation, Colorado style, was to develop, as warm, low-level air

pushed eastward off of the front range that afternoon. In addition, a warm front, slicing across the corner of

Northeast Colorado, would aid moisture convergence from about Sterling to Akron, according to Mr. Maxwell.

Upper-level winds from the southwest were to increase that afternoon over the region as a jet streak/vort max

moved over Colorado. This would enhance lift and encourage rotation of any storm activity over Eastern

Colorado. Also, forecast upper-level diffluence and lifted indices (near -10) were excellent. All of these

parameters were courtesy of an unseasonally strong and persistent upper-level trough over the Great Basin. It's

a good thing that clouds don't know what month it is!

Charlie and I had a leisurely lunch in Colorado Springs and drove north towards Denver, with the option

(very much in the backs of our minds) of jumping onto Interstate 70 and heading home to California should

nothing significant develop. Denver was hot and dry at 1 p.m.: 91 degrees, 14% relative humidity, and light

winds. At 1:30 p.m. MDT Denver NOAA WeatherRadio issued a statement concerning a small shower which

we could see to our east, near Deer Trail. I thought that those clouds hardly warranted a statement, but chasing

is in our blood and we headed east! This would definitely be our final chase, our last chance for something

special in 1993.

The cell was caught around 2 p.m. MDT, near Byers. We visited a grocery store in Byers, just

southwest of this small and isolated thundershower. I called my weather office back home for the latest update.

(I am the climatologist for Continental Weather Services, Inc., in Encino, California.) A mesoscale discussion

for the region had just been issued by Air Global Weather Central at Offutt AFB in Omaha, Nebraska (acting

in backup capacity for the National Severe Storms Forecast Center):

"Moisture convergence increasing in Eastern Wyoming and Northeast Colorado as low-level winds back

and increase in response to approach of a jetstreak over Western Colorado. Surface-based lifting index between

negative 8 and negative 11 from Eastern Wyoming/Western Nebraska southward into extreme Northeastern

Colorado. Weather Watch expected to be required within the next hour or so as energy from the approaching

shortwave increases UVV (upper vertical velocity) fields over upslope area."

By 3 p.m. MDT a tornado watch box had been issued for much of Eastern Wyoming and adjacent South

Dakota and the Nebraska panhandle. Charlie and I were not interested in driving any farther north or east than

was necessary. We had a nice little thundershower to watch, it was easy to follow, and it had good potential.

It was isolated and moving into an environment more favorable for strengthening.

Still at Byers we visited with a team from NCAR that was watching the "storm" for a hail study. Shortly

thereafter they were told to leave the storm and to head back west to their base. (I never could quite figure the

reasoning there!) Our storm, meanwhile, was developing, and we headed east on U.S. 36. From about 3 p.m.

to 7 p.m. the cell intensified and plodded ss..ll..oo..ww..ll..yy eastward, just north of U.S. 36 the entire time.

Charlie and I were transformed from storm chasers to storm perusers (not pursuers---perusers!). Just east of

Byers we sat in the truck, right underneath the storm's updraft base and amidst long cloud-to-ground lightning

bolts, relishing each crash of thunder. (Believe me, that is a real treat in itself for us California boys!) We

viewed a little landspout which spun up below the southern edge of the updraft base. We drove south a mile

or so for a better overall view of the storm. We drove east a few miles down U.S. 36 through dusty outflow

winds. Again we went a little south, then back to U.S. 36 and east again to keep up. The updraft base was quite

ragged, and the precipitation area to its north was getting darker. About seven miles west of Last Chance I set

the camcorder up on the tripod. The base of the storm was getting lower, and a wall cloud was trying to

organize. Air Global Weather Central put the Plains of Eastern Colorado under a tornado watch at 4:37 p.m.

MDT.

Finally, near Last Chance in southwest Washington County, the storm developed to a point beyond mere

mediocrity. From 5 to 7 p.m. the storm drifted from northwest of Last Chance to northeast of Last Chance.

Around 6 p.m. several gustnadoes (or, perhaps more precisely, "funnel-less debris-whirl tornadoes") spun up

simultaneously beneath a rather ill-defined wall cloud. At the same time, a "clear slot" just northwest of this

area marked the storm's rear-flank downdraft. (Also at this time, a fellow riding his bike (from east to west)

across the country stopped by to marvel---good timing, dude!) Heavy precipitation fell north and northeast of

the updraft, and greenish/aqua-marinish tinges suggested big hail. This was becoming a textbook storm. It was

moving into an ever-moister and unstable airmass. It was isolated with a capital I--free to ingest as much juicy

surface air to its east and southeast as it deemed necessary. Several other storm chasers converged around Last

Chance to see what this storm could do. The National Weather Service in Denver had southwest Washington

County under a tornado warning shortly after 5 p.m. MDT.

(The 00Z (6 p.m. MDT) weather map showed the warm front through the corner of Northeast Colorado:

from the CO/WY/NE triple-point to Brush to Burlington. This put it about 20 miles east of Last Chance.

Limon, southwest of the front, had south-southeast winds at 20 knots and a temp/dew point of 83/44. Goodland,

northeast of the front, had a southeast wind at 10 knots and a temp/dew point of 76/68. Akron, Colorado, about

30 miles NNE of Last Chance and just east of the front, had southeast winds at 20 knots and a temp/dew point

of 75/64.)

Near 7 p.m. a very-impressive-looking updraft was rotating north of Lindon, and it continued to issue

funnel clouds and brief debris-whirl tornados. The sides of this saucer-shaped updraft were fabulously smooth

and curved! At 7:20 p.m. several chase teams watched from Roads S and 15, three miles north of Lindon. We

had two additional cells to watch by then, a small one to the northwest and a new one to the southwest. The

primary cell, drifting off to our northeast, was still a monster, but it was having a lot of difficulty maintaining

its wall cloud. Charlie and I noticed that low clouds overhead were streaming towards the activity to our

southwest. Though we did not grasp the significance at the time, the storm we had been following for over five

hours was now feeding an offspring to its southwest. We were reluctant to abandon our primary cell, so we left

the chase party and drove a few more miles north and east. We stopped to look around in light rain near Roads

W and 17. Our primary storm was even more disorganized, and that little bell-shaped base to the northwest was

fizzling fast, too. Low clouds continued to race towards the cell back towards Last Chance!

Lightning in this new cell became more and more frequent, and its very low base was issuing some very

intriguing and constantly changing shapes. Though it was about 15 to 20 miles away, we had a decent view of

this base to our southwest: intervening precipitation was light, backlighting was excellent. Finally, it became

obvious that we should forsake the dying for this burgeoning tail-end Charlie cell. The time was 7:45 p.m. We

had one hour of daylight left in our storm-chase season. This was our last chance chase.

A large funnel cloud took shape as we covered the five miles back to U.S. 36 (along Road W). When

we reached U.S. 36 and headed west, our disbelieving eyes viewed a large funnel all the way to the ground!

We turned south again onto Road U (two miles later) in light rain and small hail. Now we were afforded only

occasional views of the tornado along Road U: the updraft base of the tornadic storm was very low, and the

terrain was hilly. Only at each hill crest could we see what was happening---and each time the thing was larger!-

-it was wider!--it was a big wedge tornado! Charlie and I were incredulous! This was the farthest thing from

our minds! We ARE in Colorado, are we not?

The precipitation ended as we churned southward down Road U. Five miles from U.S. 36, we came

upon a road west, Road 7. Road 7 headed straight towards the black, menacing, deadly monster! Anticipation,

anxiety, and exhiliration reached new heights for Charlie and me! This was our first real tornado---not just some

wimpy landspout or funnel-less dust whirl! I turned right on Road 7. I punched the accelerator again and

honked at a farm worker who was working with some equipment by the road. He did not appear to be aware

of the impending doom spinning a few miles away.

Which way was the tornado going? Probably towards us. Which way were we going? Definitely

towards it! How close, how scared, how daring did we want to be? It took us only one mile to decide. We

stopped at Road T. It was 8:00 p.m. The tornado still appeared to be three or four miles west of us, but it also

looked at least one-half mile wide! It was not moving forward very fast, however. I pointed the truck east, left

the engine running, and we hastily set up the camera tripods. We both felt that we would not be able to linger

very long at this site. We had escape routes only to the north and east (and west???).

The weather where we were was wonderful--the view spectacular! We were alone! (Where are those

other chasers?!) Charlie's camera clicked away and I monitored the camcorder as the tornado slowly approached.

We had an excellent view---there was NOTHING to obscure this grand vision! Sunlit skies framed the black

and ominous wedge. How did we feel? We felt awestruck; we felt blessed. This was not Colorado--this was

heaven!

The tornado slowly moved east-southeast and gradually became smaller and more compact. Its right-

moving path took it to our southwest--about two miles away--but its base was now less than a quarter-mile wide.

At this point Charlie and I became more concerned (safety-speaking) with the dark wall of storm encroaching

from the northwest, and the classic supercell rotating directly overhead. Thunder to our north sounded like

shotgun blasts--perhaps thunder trapped in a chamber of hail. We were in no-man's land: We were in heaven,

surrounded by hell.

An amazing sequence of events was about to transpire as the tornado continued to our southwest. Its

base began to dissipate, and for a few moments we could see a multiple-vortex structure. Just when it seemed

that total dissipation was near, a needle-thin funnel suddenly formed inside of the larger, largely transparent

circulation. This "needle-in-the-funnel" was on the ground and it quickly expanded. The large, squat, wedge

tornado had transformed into a tall canister, or, columnar, shape. One-half minute later, the lower portion

dissipated again, but once more a narrow funnel cloud quickly redeveloped along the ground. The tornado took

the shape of a slender, classic-looking twister, then changed back to a canister shape again. To our south-

southwest it stood at an angle in "Tower-of-Pisa-like" formation. It quickly roped out over a dusty field, still

south-southwest of us, about ten minutes after we had arrived at the intersection of Roads 7 and T in Washington

County. (Was "7" for luck, was "T" for tornado?)

How fortunate could two storm chasers be? We had just captured some of the most incredible and

spectacular tornado video ever! We were provided with a large, slow-moving and dynamic tornado from a

tranquil, obstruction-haze-and-dust-free viewing site with great backlighting and contrast. What do we do now?

Well, we had to try to stay alive. I thought that we might have to pay for our luck by sacrificing the

integrity of the chase vehicle. Fortunately, large hail skirted by just to our north, and just a few golf-ball-sized

stones sprinkled our vicinity.

A minute or two after the tornado roped-out, a couple in a truck drove up to us to see what we were up

to. He had watched the tornado from a field on his farm; she had seen us from their farmhouse, wondered if

we were stuck or something, then glanced west and fled to the basement! Now the tornado was gone, and we

went a quarter of a mile west to take refuge from the impending wind, rain, and hail at their home. Their home,

right on Road 7 and directly east of the tornado's birthplace, was spared because the tornadic storm turned a little

to the right.

From the porch of the home of Philip Scott I videotaped the storm as it swirled a few miles to our east-

southeast. The base was incredibly low, and the land below it appeared to be awash in hail. Another large

tornado developed beneath this airborne maelstrom as darkness fell, and we did not see it. Little did we care.

Charlie and I had just completed the chase of our lives. Our last chance chase had become The Last Chance

Chase; our Last Chance chase was a Gentleman's chase, an E-ticket chase from heaven.

Notes of interest concerning the tornados: These tornados of July 21, 1993 were actually a little closer to Lindon

than Last Chance. They are among the largest ever witnessed and photographed in Colorado. The first tornado, the one

Charlie and I videotaped, was rated F0 because no structural damage occurred. It injured some animals and tore

up some fences, but otherwise hit nothing! The second tornado wrecked a farmhouse and was rated F3. There

were no deaths or injuries. Another out-of-season tornado killed eleven people just east of nearby Thurman,

Colorado, on Sunday, August 10, 1924. (I believe that that one still remains Colorado's only killer tornado on

record.) The tornado that tore through Limon, Colorado, in 1990 was on June 6. Tornado season in Eastern

Colorado is generally considered to be mid-May through June. The jet stream is typically too far north of the

state during July and August for storms such as these.

There were perhaps a dozen or so chasers and spotters in and around Last Chance and Lindon that evening

watching the storm. Apparently, most did not end up in very good position to view Tornado #1. Dean

Cosgrove, a NWS spotter out of Fort Morgan, was in good position and saw the large wedge of Tornado #1

develop from Roads W and 7, three miles east of our site. Dean managed to stay safe, videotape the storm, and

keep the Denver NWS up-to-the-second on the status of the storm and tornados. He was on the storm from

about 4 p.m. to midnight, when it finally weakened near the Kansas border. Another chaser from Denver, Tim

Samaras, watched the large wedge develop just to his north while along Road M. Tim's video of the tornado

as it drifted to his east is spectacular, but he was fighting rain, strong winds, and poor contrast as precipitation

wrapped around the west side of the tornado. Dave Thede and Dave Solomon caught the end of tornado #1

about eight miles east of where it roped out. From there they had a great view of the second large tornado as

dusk fell.

Charlie and I called Channel 4 in Denver from the Scott's farmhouse south of Lindon and met their newsvan

at Byers at 10 p.m. Our tornado footage was seen on the Denver news within the next 15 minutes, and Charlie

and I began our happy trek west along I-70. When we arrived home in Los Angeles the next evening we saw

our tornado footage again--on The Weather Channel!--which had been showing clips of the incredible storm all

day long.