Welcome to another edition of my research into the old Death Valley temperature record. This is Part 6. To find links to all of the parts, go to Part One HERE. Much credit and thanks for this section go to the museum at Independence and its Pacific Coast Borax Company archives.

December 2, 2017 UPDATE note: I have been adding new information to this “Part 6” in the last month or so. This entry can be considered “complete” for the time being, barring any discovery of new and relevant information. Of course, that is always very possible!

September 3, 2022 UPDATE: More info on Oscar Denton added at the bottom.

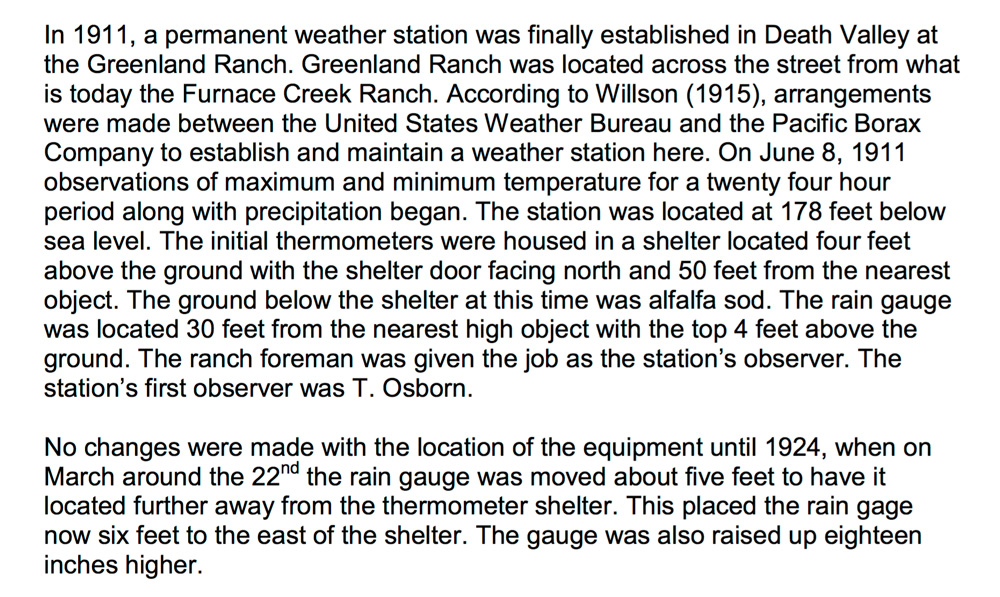

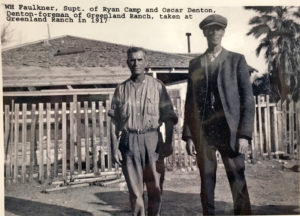

Since it is my contention that the record maximum temperature reports at Greenland Ranch of 127F to 134F from July 8-14, 1913, are not credible and were due to observer error (Denton may have intentionally inflated the actual and authentic readings), it might be instructive to learn more about the observer, the weather station, and the ranch. Oscar Alan Denton was the observer for the Greenland Ranch weather station in Death Valley from 1912 to 1920. As the caretaker and foreman at the ranch, the weather observing duties fell to Denton somewhat by default. The Greenland Ranch weather station opened in June 1911. Fred Corkill was the superintendent of the ranch and the associated borax mining there, and he relegated the weather observer duties to his ranch foreman. For the summer of 1911 and into the summer of 1912, the observer was Thomas Osborn. It appears that Osborn was unable to make it through the summer of 1912, and by September or October, Oscar Denton was the new ranch foreman, caretaker, and weather observer. The ranch was basically shut down due to the excessive heat from about June through September, and the caretaker might be the only one there for weeks or months at a time. Visitors to the ranch during the summer were probably very infrequent. What was Denton like? What was his schooling and his background? What was ranch life like in the summer? This entry looks into the life of Oscar Denton and the earliest caretakers at Greenland Ranch. It also explores some of the history leading up to the establishment of the Greenland Ranch weather station, some history of temperature measurements prior to 1911 in Death Valley, and some questions and explanations with regard to movements of the weather station.

The Earliest Greenland Ranch Caretakers, Including James Dayton

Borax was discovered just north of what is now Furnace Creek Ranch around 1881, and was processed at the Harmony Borax Works from about 1883 to 1888. The 20-mule teams hauled the product to the railroad at Mojave during this 5-year period. Other (shorter) mule trains were employed to transport supplies to and from Daggett, on the Santa Fe Railroad. These places were about 165 miles from the Death Valley borax operations, and a roundtrip from Harmony to Mojave and back took twenty days. Below are some links on the history of borax mining in the Furnace Creek and Ryan area:

A brief history of Borax Mining in the Death Valley region

A brief history of Furnace Creek Ranch

Wikipedia entry for Furnace Creek Ranch

History of Borax and Ryan on Desertfog.org (by Jack Freer)

Borax history timeline on Desertfog.org (by Jack Freer)

Ryan today and the Death Valley Conservancy

A Master’s Thesis on the Ryan District by Mary Ringhoff (2012 USC)

The mine’s owner, William T. Coleman, established a ranch near the mouth of Furnace Creek in order to support the mine operation and to house his company’s (approximately) 40 laborers. In 1883, Coleman’s superintendent, Rudolph Neuschwander, laid out Greenland Ranch and its forty acres, and built the ranch house (Lingenfelter, p. 180). Water from the springs in Furnace Creek Wash was more than adequate to allow the irrigation of forty acres for alfalfa and other crops. This lush and green oasis amidst the bleak and barren expanse of Death Valley resulted in the name of “Greenland” for the ranch. Coleman’s other business ventures failed in 1889, and by 1890 Marion “Borax” Smith owned the ranch and borax mining operation in Death Valley. Greenland Ranch was now part of the empire of Borax Smith and his “Pacific Coast Borax Company.” The company’s more profitable (and less remote) mines resulted in the closure of Harmony Borax Works by Smith by 1890, but the nearby ranch and its farmland were maintained.

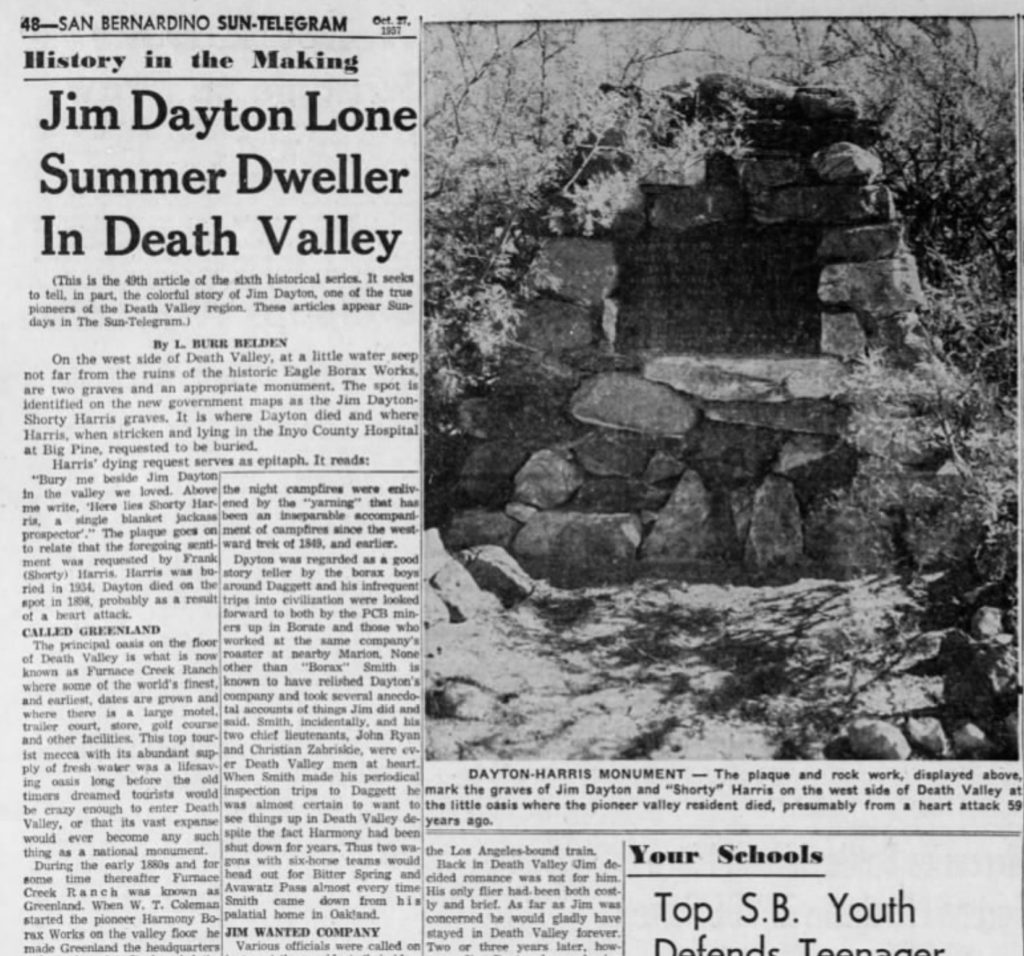

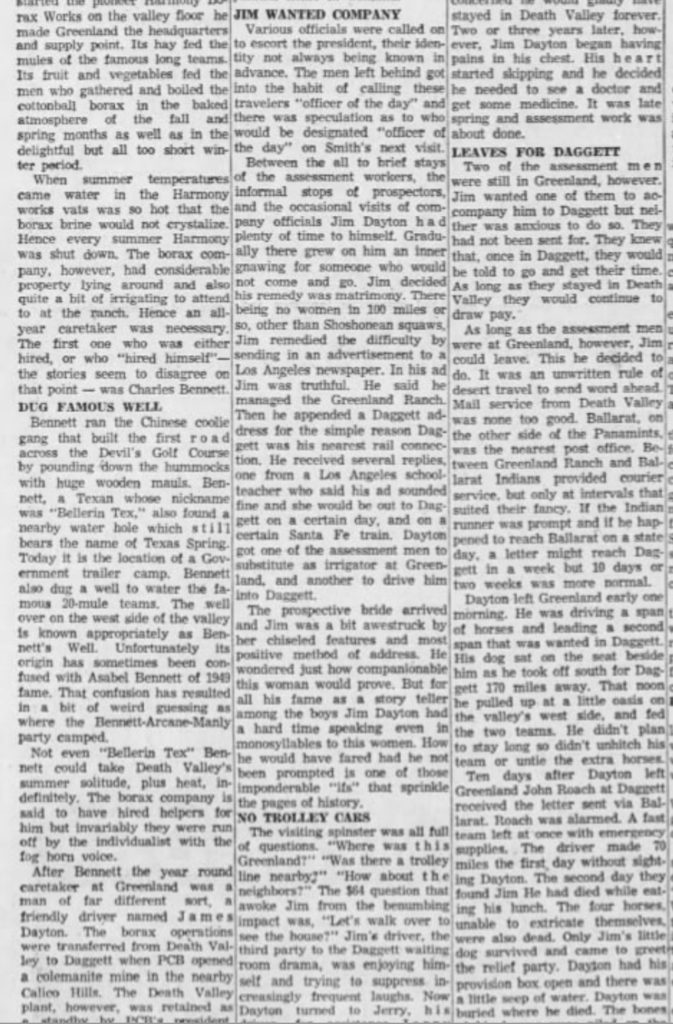

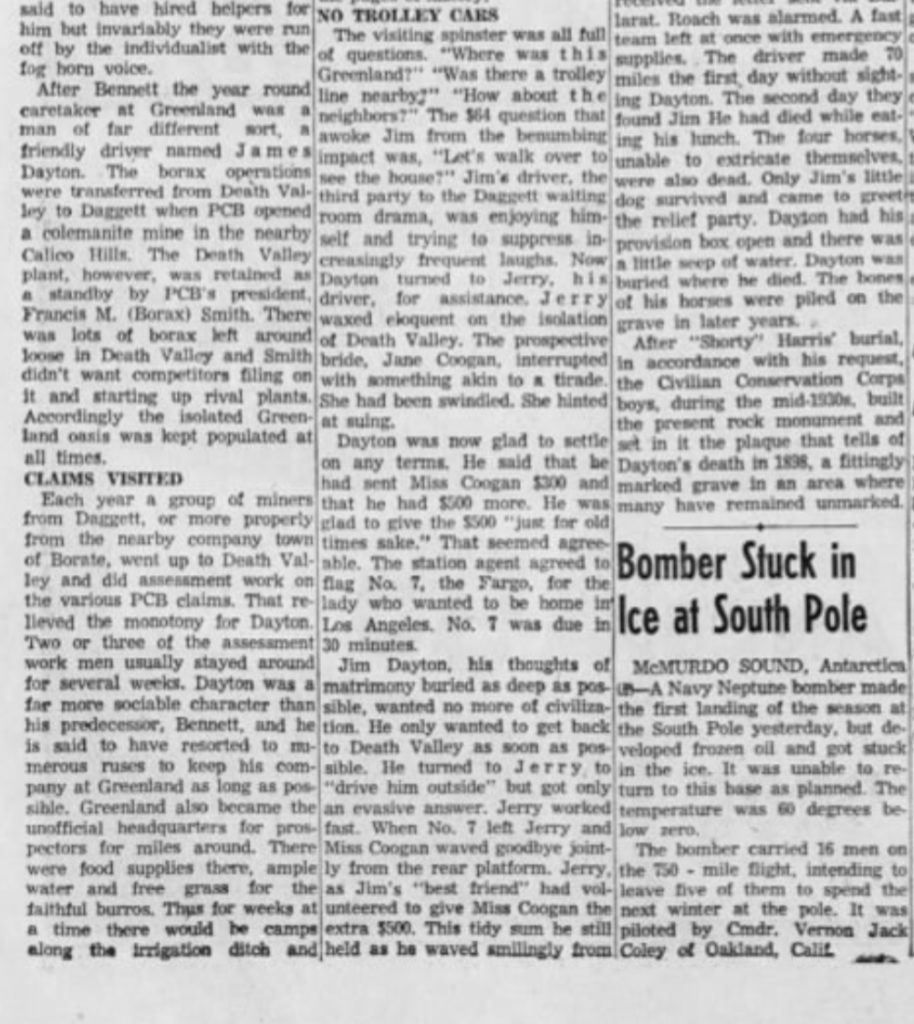

Because of the hot conditions, the Harmony works did not operate from early June to about October 1. The laborers were moved to operations in the less-oven-like Amargosa Valley (near Shoshone and Tecopa) during these months. Two men typically remained, at least intermittently, at the ranch during the hot summers (Lingenfelter, p. 181). The first caretaker was Charles Bennett, to be followed (around 1884) by James (Jimmy) Dayton. Dayton was one of two caretakers in 1890 when the ranch ownership changed. The early summer heat of 1890 prompted the other caretaker to try to escape Death Valley by foot, but he died about 40 miles from Greenland Ranch. James Dayton remained as caretaker here until July 24, 1899. On that date he began a trip from Greenland Ranch to Daggett, utilizing mules and a wagon. His body was found about 20 miles south of his starting point about one month later. An article about Dayton’s life and death in Death Valley (provided below) appeared in the San Bernardino Sun-Telegram on Sunday, October 7, 1957.

On August 25, 1899, The Los Angeles Herald contained the following article regarding Dayton’s death:

A HORRIBLE DEATH James Dayton Perishes Miserably in Death Valley

Daggett, Cal., Aug. 24.—Death Valley has claimed another victim. Nearly a month ago James Dayton, crossing the desert with a team of six horses, perished miserably from illness or the effects of the heat. Then there was no one to care for the animals and they died from hunger and thirst, although there was plenty of food and water in the wagon. Dayton was caretaker for the Pacific Coast Borax company at Furnace creek, in Death Valley, about 150 miles from Daggett, the nearest railroad and supply station. A little traveled desert road is the connecting link and there is one stretch of seventy miles over which no water can be had. Dayton, who was 70 years old, started from Furnace creek for Daggett July 24th. Aug. 9th a letter was received at Daggett from Furnace creek saying that Dayton had started on the first mentioned date. As he did not arrive, a searching party was made up. It traveled to within twenty miles of Furnace creek before the tragedy became known. On “‘Aug. 11th Dayton’s body was found within a few miles of Bennett’s Hole under a mesquite bush, under which he had laid down to die. Fifty feet away were the wagon and the bodies of the horses. The latter had struggled most frantically to release themselves, but in vain. If Dayton had realized that he was going to die he would have released the animals. There was one survivor—Dayton’s little dog, which for twenty days had kept watch and ward over its dead master’s body. It is thought that the dog got water half a mile away and managed thus to survive. The weather at Furnace creek was unusually cool since Aug. Ist—only 120 degrees in the shade.

Dayton’s grave marker (erected in the 1930s) indicates that he perished in July of 1898, but the L.A. Herald article and Lingenfelter’s Death Valley and The Amargosa, A Land of Illusion state that he died in 1899. Also, though the article above says that Dayton was 70 years of age, the “find a grave” web site shows a birth date of February 29, 1832, which means that Dayton was 67 years old in July, 1899. Assuming that Dayton’s ill-advised trip occurred in 1899, weather records at Independence, California, suggest that the maximum temperature in Death Valley on July 24 was close to its long-term average, or around 115F to 116F. Maximums at Independence from July 21 to July 25 in 1899 ranged from 93F to 95F (with 95F on the 24th), compared to its average daily maximum of 94F for Julys prior to 1930.

Some Early Temperature Measurements in Death Valley

According to Lingenfelter (A Land of Illusion, page 5), “The first actual measurements of summer temperatures in Death Valley, made by the Wheeler survey in the 1870s, showed a maximum of 121F, which the Army Signal Corps proclaimed the highest temperature ever recorded in the United States.”

On July 3, 1890, the air temperature reached 136 degrees F “according to observations by James W. Dayton.” (Chronology of the Death Valley Region in California and Nevada, 1849-1949 by T.S. Palmer, 1989). I have yet to find any other details regarding this or any other temperature measurements by Dayton.

While Dayton was caretaker, from May to September in 1891, a temporary weather station was established near Greenland Ranch by the U.S. Weather Bureau (Harrington, 1892). See Part One of this study. The highest temperature during the summer of 1891, inside of the standard USWB thermometer shelter, was only 122F (on several dates). Two observers were tasked to work the summer of 1891 at the ranch for the Weather Bureau, but shortly into the period one observer (Mr. R. E. Williams) suffered from the heat and had to be taken to Keeler to recover. John H. Clery was the USWB observer who was able to make it through the summer of 1891 at the Harmony Borax Works, near Greenland Ranch.

An article titled Death Valley by Professor Oscar C. S. Carter appeared in the Scientific American Supplement, Number 1442 (August 22, 1903). It provides additional details with regard to the 1891 weather study: “In 1891 the botanical expedition headed by Frederick Vernon Coville, with Frederick Funston assistant, explored this region. It was directed by Hart Merriam. This expedition was made with the cooperation of the United States Geological Survey and Signal Service, and was continued by Mr. John H. Clery, of the Weather Bureau, under the direction of Chief Mark Harrington.” Carter’s article summarized some of the observations by Clery in 1891, as found in Harrington’s 1892 report. The author notes that the accepted hottest temperature on record for the United States, as of 1903, is the 128F report from Mammoth Hot Tank in the Colorado Desert.

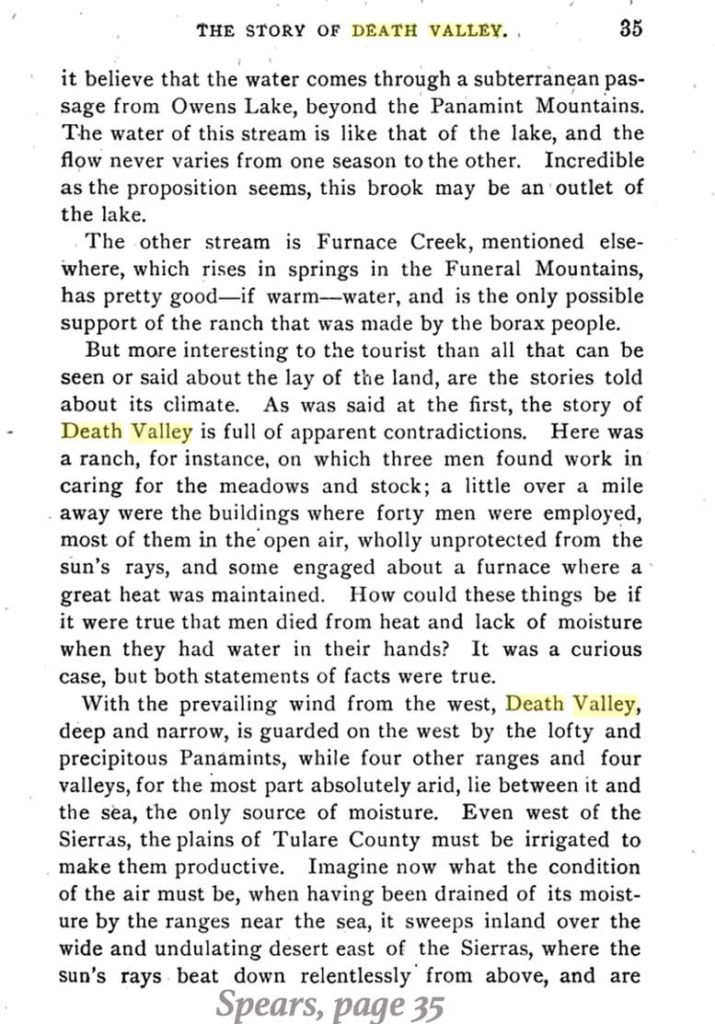

Reports of temperature readings of 130F or higher in Death Valley were not particularly unusual before the official Greenland Ranch station was established in 1911. These high readings were, at the time, considered reasonable (presumably) by those who checked the thermometer, in part because they were made in the shade. “A thermometer hanging under the wide veranda on the north side of the adobe house on the Death Valley ranch, has registered 137 degrees,” according to John Randolph Spears’ in Illustrated Sketches of Death Valley and Other Borax Deserts of the Pacific Coast, published in 1892. Spears does not provide any other information about this measurement. Chances are good that Dayton provided the figure to Spears, and it may have been Dayton who made the actual thermometer reading. We do not know the type of thermometer and its reliability and accuracy, and it is probable that this same thermometer provided Dayton with the 136F temperature on July 3, 1890. (What kind of regular household thermometers were calibrated up to 140F before 1900?) With regard to the siting of the thermometer beneath the veranda: it is good that the instrument was in the shade and not in the direct sunlight, of course. But, it is much too close to the house to provide relatively legitimate, or reliable, ambient air temperature readings ALL of the time. The north side of a structure (in the Northern Hemisphere) is generally the best side for such a thermometer in order to avoid direct sunshine, and to provide relatively reliable air temperature information most of the time. For the cool half of the year, direct solar insolation would not hit the north side of the house. But on summer afternoons, during the hottest time of the day at Greenland Ranch (3 p.m. to 5 p.m. PST), the sun comes around to the west-northwestern part of the sky. Direct sunlight would be beating down on the ground near the thermometer, and on the north side of the structure. The thermometer may be shaded, but it is close to very hot surfaces. Furthermore, the house is effectively blocking the typical southerly (afternoon summer) breeze, reducing mixing on the north side of the residence. The poor exposure, the limited ventilation and the nearby direct sunlight would contribute to a warmer environment beneath that veranda on the north side of the adobe house. Thus, the readings of greater than 130F by this thermometer, while likely authentic for its particular and inadequately-exposed locale, would not be accepted as trustworthy and valid by a climatologist.

Spears also shares a statement regarding very high temperature measurements in Death Valley by James J. McGillivray, a mineral surveyor working for Coleman’s borax company: “The heat there is intense. A man can not go an hour without water without becoming insane. While we were surveying there we had the same wooden-case thermometer that is used by the Signal Service. It was hung in the shade on the side of our shed, with the only stream in the country flowing directly under it, and it repeatedly registered 130 (degrees), and for forty-eight hours in 1883, when I was surveying there, the thermometer never once went below 104 (degrees).”

So, as early as 1883, it was revealed and known that temperature soared to as high as at least 130F in the shade in Death Valley. Because the measurements were made by the Signal Service and their quality thermometer, in the following few decades there was little reason for anyone to think that legitimate temperatures of 130F or higher in Death Valley were particularly rare or unusual.

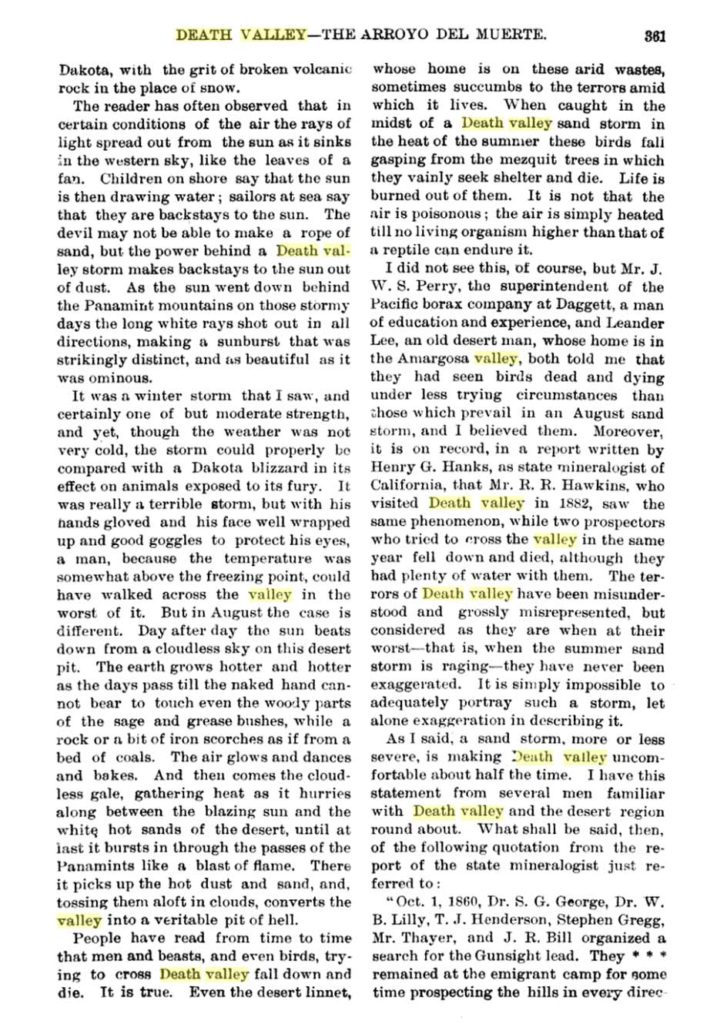

These excerpts are from the interesting section concerned with Death Valley weather and climate in Spears’ book. Below are the parts taken directly from the 1892 edition (courtesy of Google Books):

And below is the entire weather and climate section from Spears’ book, Illustrated Sketches of Death Valley and other Borax Deserts of the Pacific Coast, as it appears in Goldthwaite’s Geographical Magazine, Volumes 3 and 4, 1892:

Below is a photograph of Greenland Ranch, by Spears (in Illustrated Sketches of Death Valley and other Borax Deserts of the Pacific Coast) circa December 1891.

Early Pacific Coast Borax Company Correspondence With Regard to Greenland Ranch and the Establishment of the Weather Station

As mentioned, borax operations at Harmony (just a mile or so north of Greenland Ranch) ended in 1888, James Dayton was the caretaker at Greenland Ranch from about 1885 to 1899, and Francis Smith’s Pacific Coast Borax (PCB) Company owned and oversaw the ranch beginning in 1890. The ranch was a rather lonely outpost from 1890 to 1910 or thereabouts, with just the occasional visitor or miner passing through. The ranch continued to grow alfalfa and assorted fruits and vegetables, and to raise farm animals for eggs and meat. These products helped to support mining camps and towns in the region, such as Rhyolite and Ryan. The Pacific Coast Borax Company focused on operations at Borate (in the Calico Mountains north of Daggett) from about 1890 to 1907. Smith shifted operations back north to the Lila C mine and (Old) Ryan (near Death Valley Junction) in 1907 when the Borate deposits played out. Thus, Greenland Ranch again became an important supplier of food and feed for Pacific Coast Borax Company operations.

Some old PCB correspondence and photographs are located at the museum in Independence, California. The letters include some pertinent information on the ranch and its climate and the establishment of the weather station. Let’s examine these in chronological order. These images were taken with an iPhone, so please excuse any glare or focus problems!

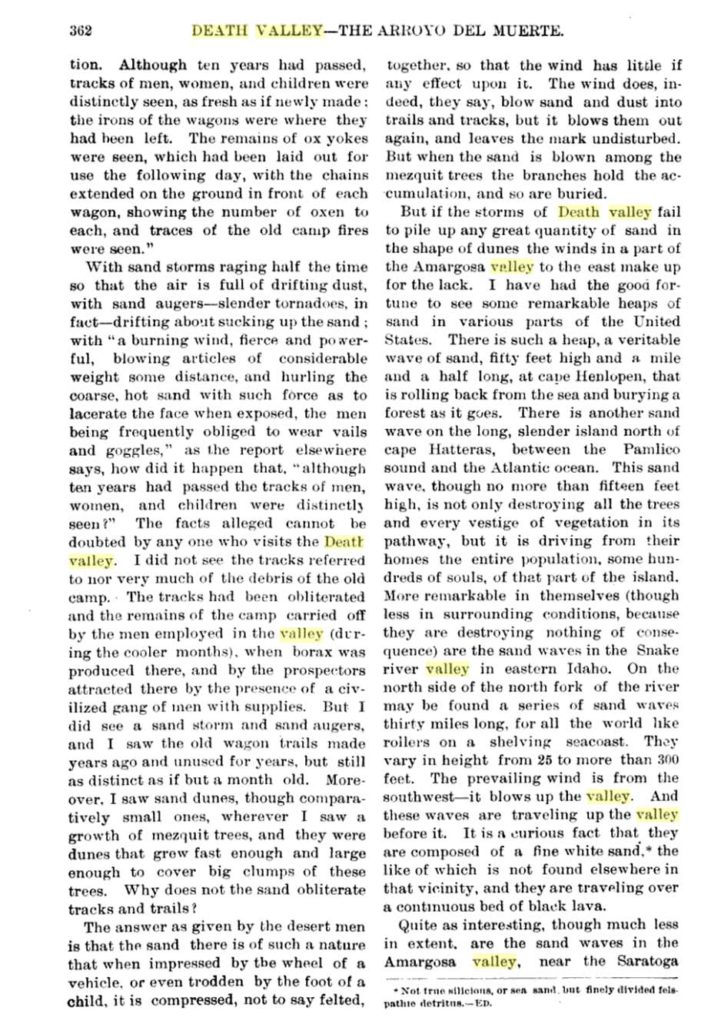

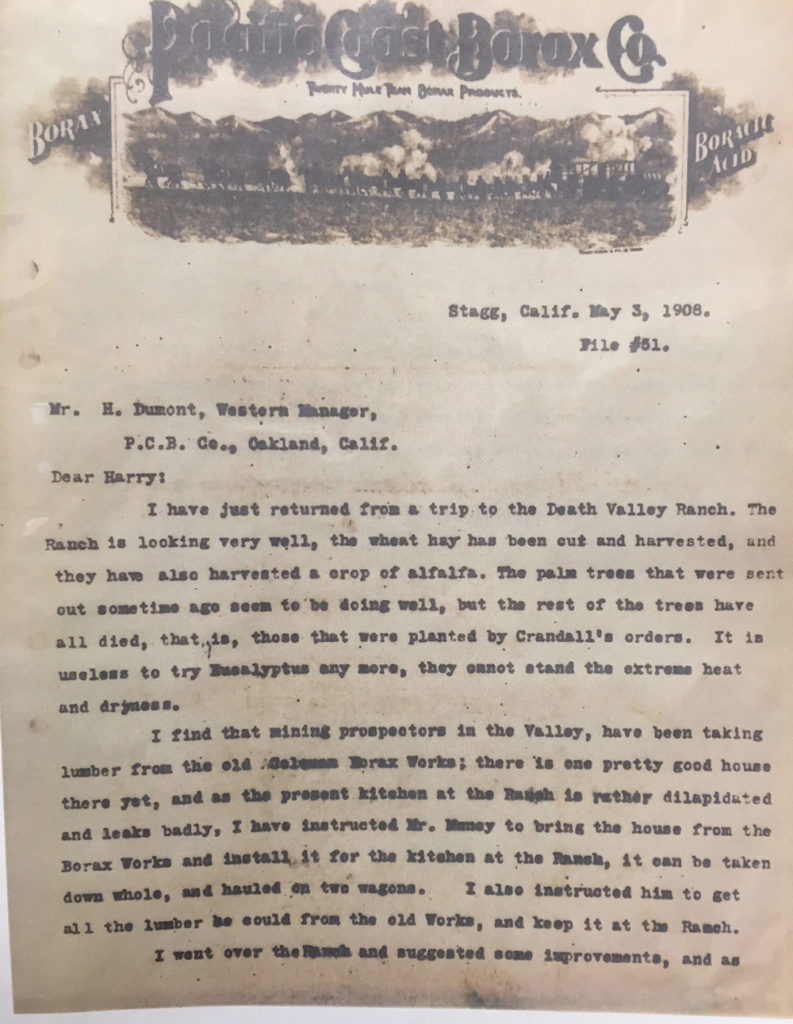

The letter of May 3, 1908 (first two pages shown above) may have been from PCB company field engineer John Ryan. The last name is not clear on the copy. It was sent from Stagg, near Stockton, California, to Harry Dumont at the company office in Oakland. The letter’s author discusses the condition of Greenland Ranch and mentions “Mr. Muncy,” presumably the ranch foreman and caretaker. I do not know when Mr. Muncy started work as foreman, but he is mentioned in correspondence as late as April, 1911. The third image above lists the Greenland Ranch inventory in October of 1908.

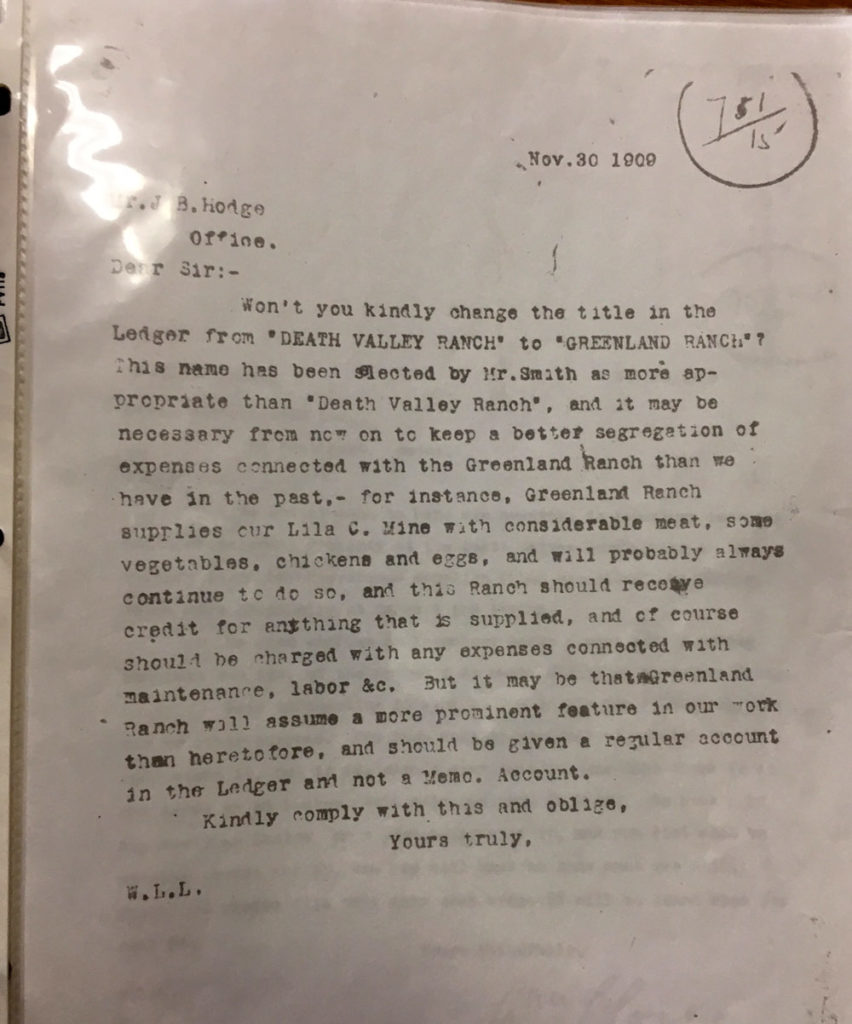

The letter of November 30, 1909 (above left) is from William Lovering Locke to a Mr. J. B. Hodge. W.L. Locke was a director for the Pacific Coast Borax Company, and he instructs Hodge that the company’s ranch in Death Valley is to be known as “Greenland Ranch,” per the wishes of the company president, Francis Marion (Borax) Smith. This is only 18 months prior to the establishment of the cooperative weather station, and is likely a big reason why the new weather station was named “Greenland Ranch” and not “Death Valley Ranch” or “Furnace Creek Ranch.”

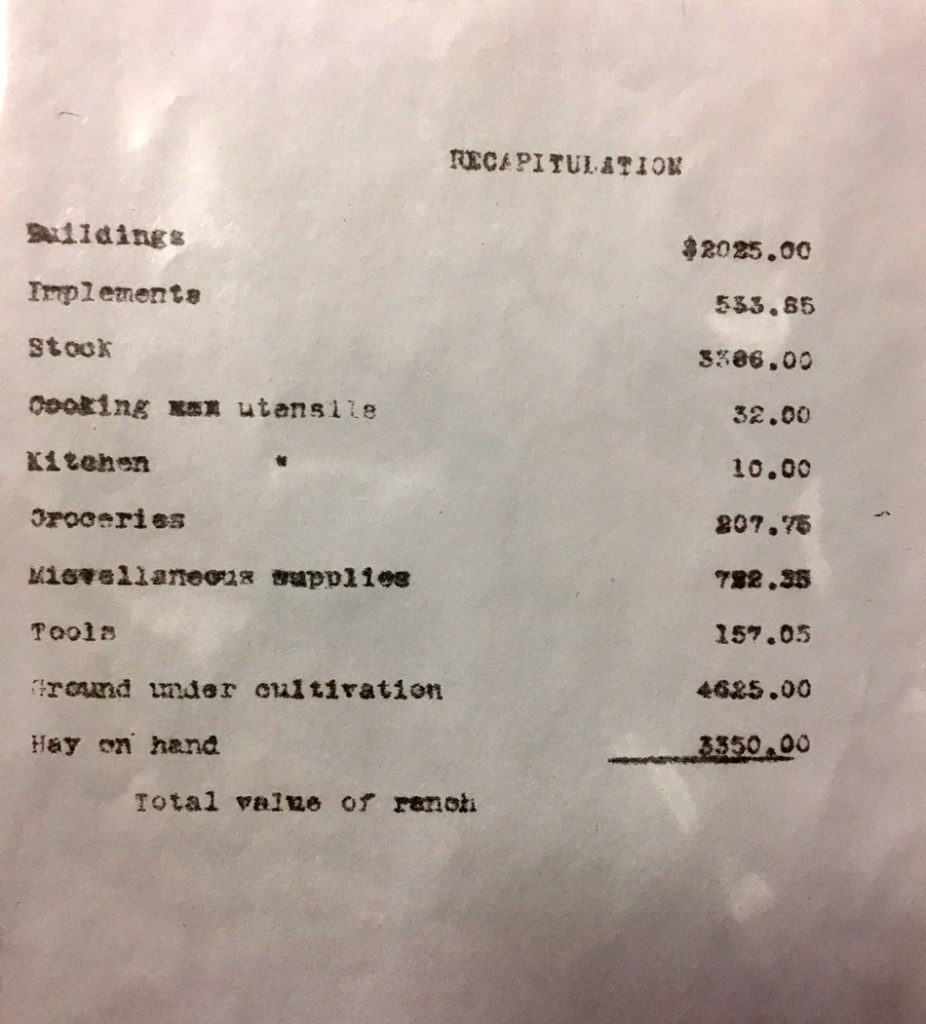

The letter of December 18, 1909 (middle and right, above) is from Locke to corporation higher-ups in London. It is concerned with the inventory and worth of Greenland Ranch.

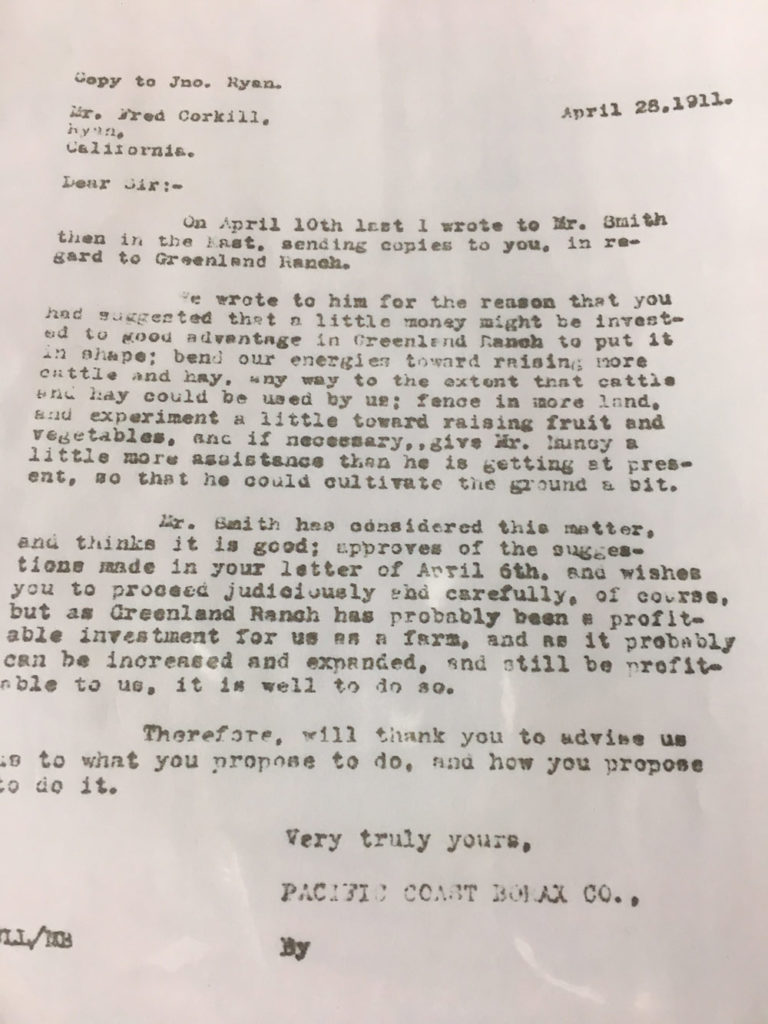

The letter of April 28, 1911 (above) is from William Locke to Fred Corkill, ranch superintendent. It is important in that it shows that the company is committed to investing in and improving Greenland Ranch. The weather station was established only six weeks later. It is quite possible that the U.S. Weather Bureau (McAdie and/or Willson) in San Francisco had already contacted Locke or other Pacific Coast Borax Company officials in Oakland regarding a new official station in Death Valley. If the company had not been committed to supporting its ranch, then the USWB might have been hesitant to provide instrumentation in 1911. There was one other issue: if the USWB and PCB established a station at Greenland Ranch, would there be someone willing to spend the entire summer at the ranch to take the daily observations?

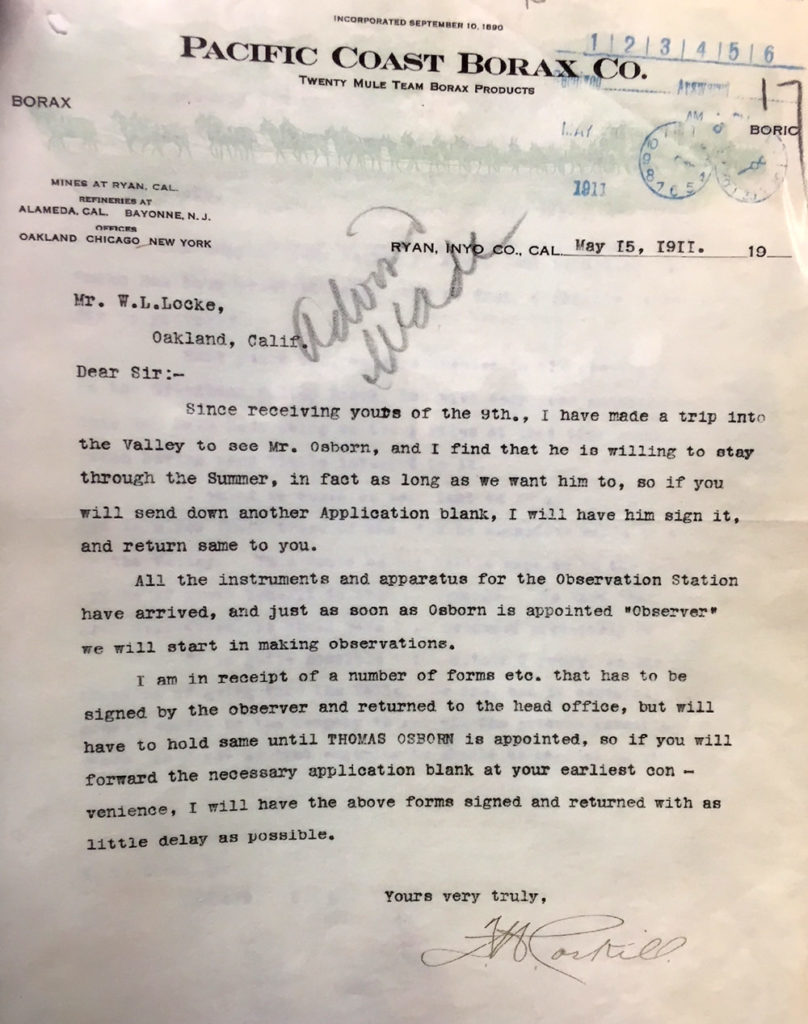

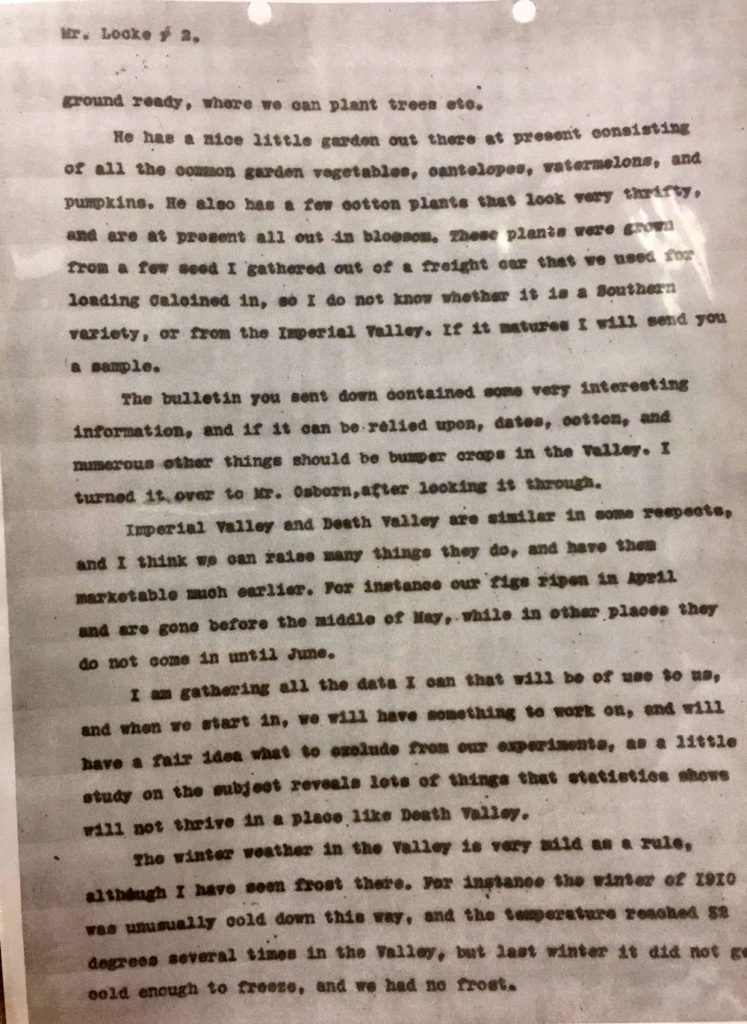

And the answer to the previous question is provided in Corkill’s letter (above) to his superior in Oakland, William Locke. On May 15, 1911, Corkill reports that a “THOMAS OSBORN” is willing to stay at the ranch through the summer and to take the daily weather observations. The equipment had already arrived at Greenland Ranch, and Corkill was waiting for some paperwork so that Osborn could be officially appointed as observer. Based on this letter, it appears that Osborn replaced Muncy as ranch foreman and caretaker in the spring of 1911, if not a little prior to that.

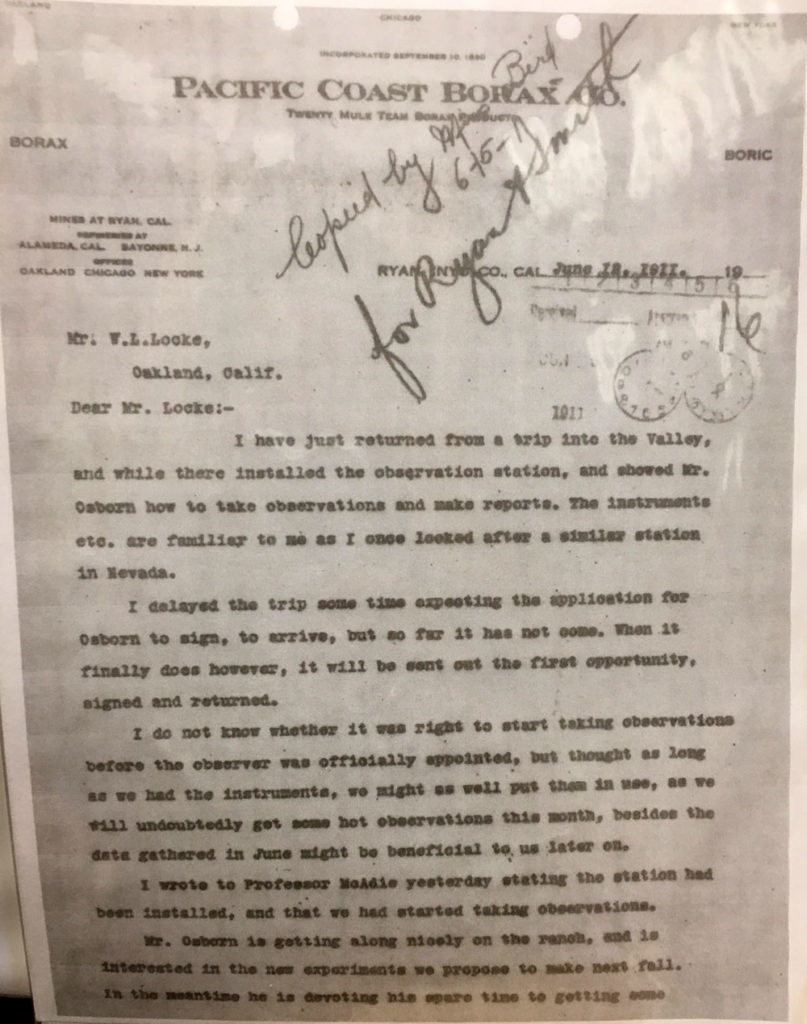

Corkill wrote to Locke on June 12, 1911 (see letter above), four days after the first official Greenland Ranch weather observation was made. Corkill reports that he set up the station, instructed Mr. (Thomas) Osborn on how to make and record observations, and that he mailed a progress report to Professor McAdie of the USWB. Corkill had been the USWB’s official weather observer at Candelaria, Nevada, from February, 1895, to May, 1898. As he states, he was familiar with the weather equipment and instruments. Thomas Osborn was the Greenland Ranch observer for only about one year. What might be important is that a USWB employee was not at Greenland Ranch when the station was set up, and the station’s first observer was not briefed firsthand by the USWB. Did Corkill alone make the determinations as to where to site the thermometer shelter and the rain gage? Was he guided by the USWB? Was there an observer’s handbook of some sort to aid the inexperienced observer? Regardless, there is no reason to believe that the Greenland Ranch station was not properly sited and erected by Corkill.

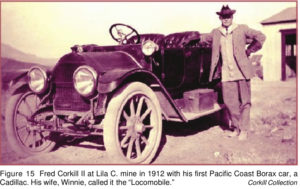

Corkill is an important figure with regard to the 134F temperature record, as discussed elsewhere. He worked as mill superintendent from 1911 to 1925 (see page 9) for Borax Smith and the Pacific Coast Borax Company at Death Valley Junction, and he supervised the foreman/caretaker at Greenland Ranch.

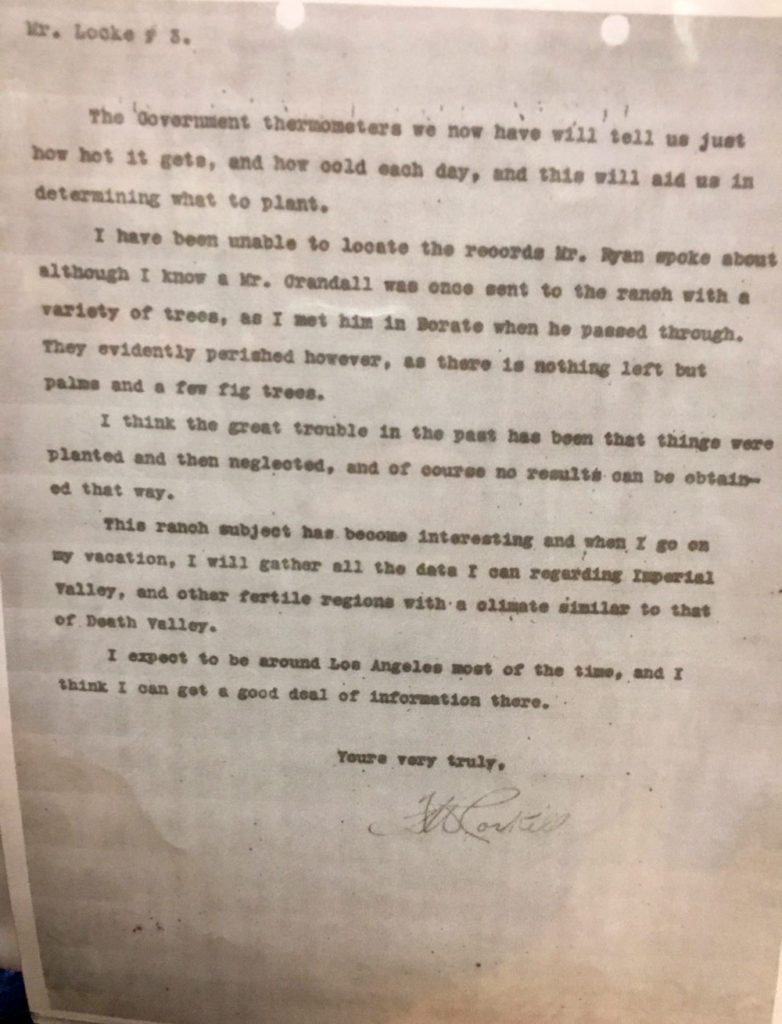

From the Corkill/Bergtold family collection:

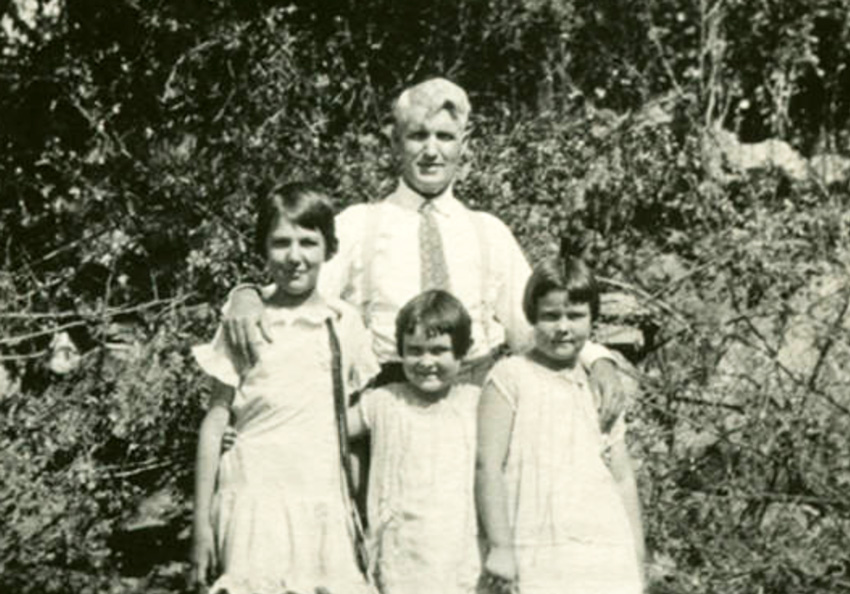

From the same collection (for the photo above): Frederick Corkill is pictured with his daughters Louise (center) and Mabel (right) and a niece. Frederick was born in 1856 on the Isle of Man. He immigrated to the United States in 1874, and became a naturalized citizen in 1882. He was a mining engineer for F.M. (Borax) Smith in Death Valley, home of “20-Mule Team Borax.” Later he became the superintendent of Smith’s West End Silver Mine in Tonopah, NV.

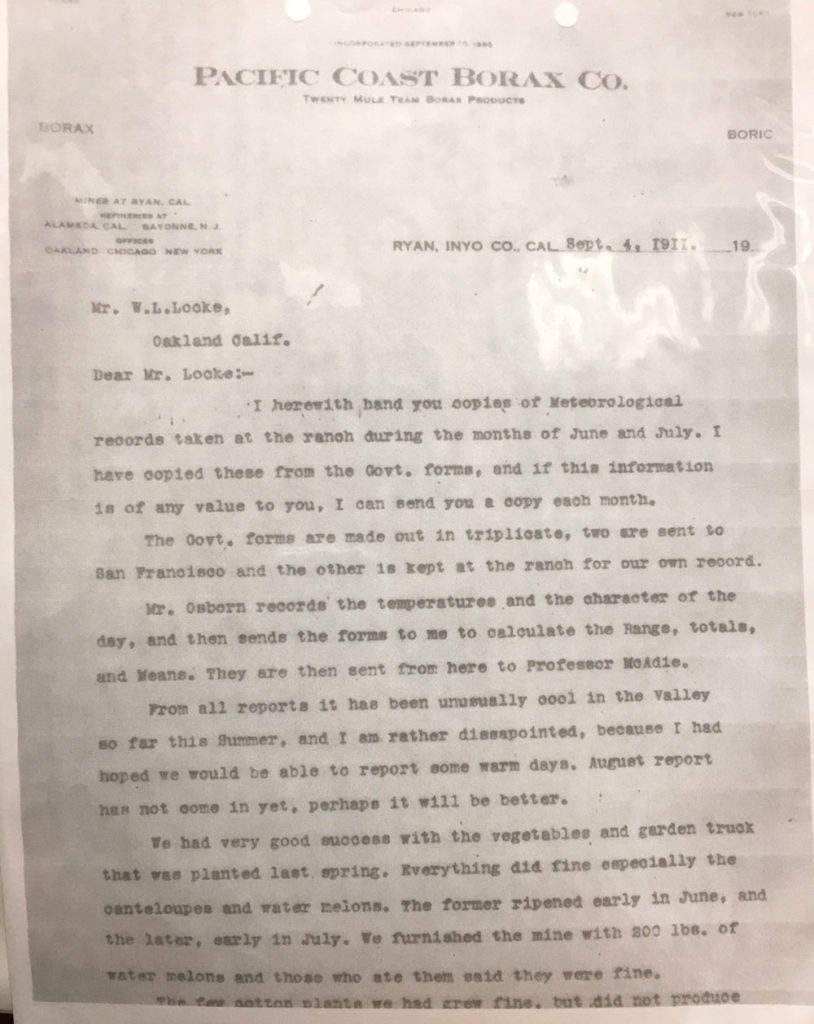

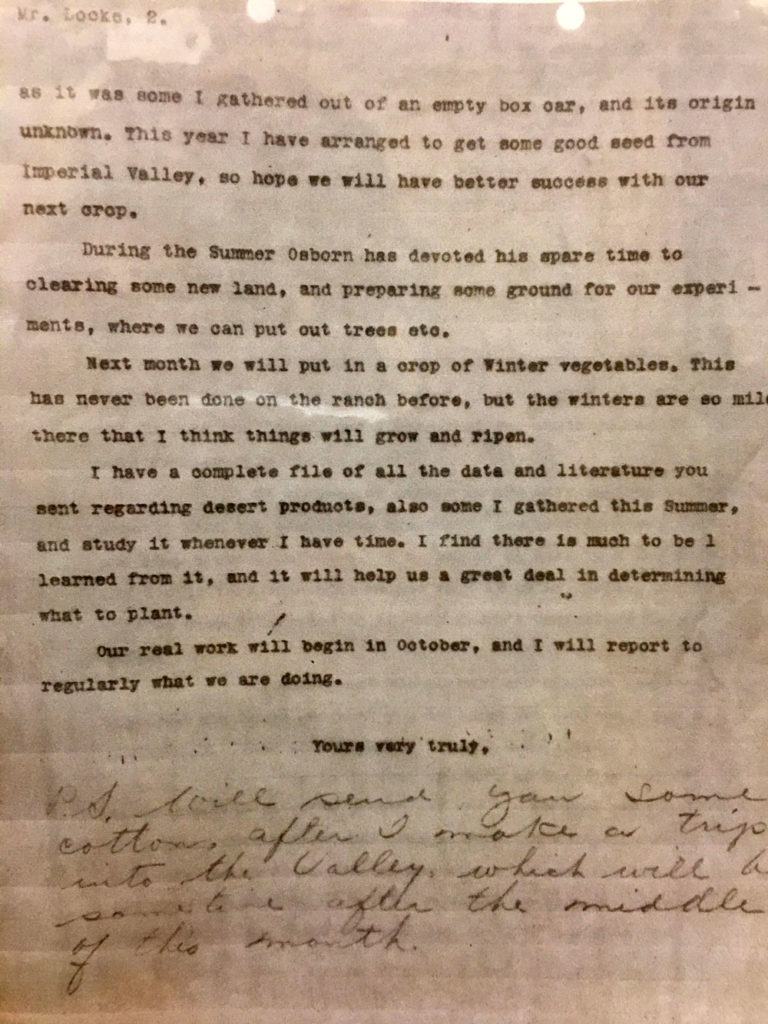

The signature for the letter to William Locke of September 4, 1911 (above) is not visible, but the letter is almost certainly from Fred Corkill. It was from Corkill’s headquarters at Ryan, just up the road from Furnace Creek/Greenland Ranch. And, the writer states that Osborn “sends the forms to me” for additional calculation of the range and means, etc. Corkill was Osborn’s supervisor and would have received these forms.

Above are copies of the climate forms for June and July of 1911 at Greenland Ranch which were reportedly included in the letter to Locke from Corkill. These show the entries by Osborne and Corkill, with the obviously differing handwriting. Corkill entered the figures in the “range” column and the summary data on the right. The letter suggests that all of the weather observations from Greenland Ranch went through Corkill (or the ranch superintendent) first before being mailed to the U.S. Weather Bureau in San Francisco…at least during these early years.

The letter to Locke from Corkill is somewhat telling. One day in June and six days in July showed maximums of 120F to 122F, yet Corkill laments that he is “rather disappointed” as he had hoped to “report some warm days.” Corkill chalks it up to the summer being “unusually cool” thus far. Corkill no doubt was well aware of the (non-standard) readings in the shade of 130F and higher at the ranch in the past on the hottest summer days. In this letter he admits his disappointment with the official maximum temperature reports for these two summer months.

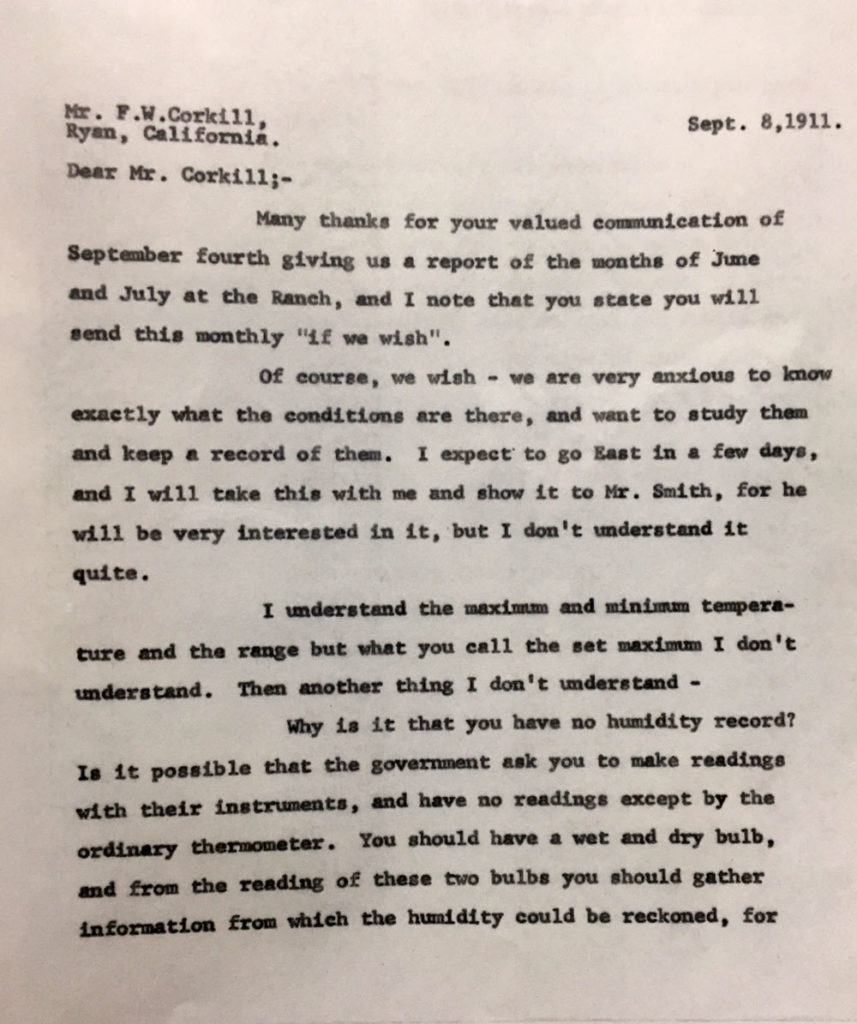

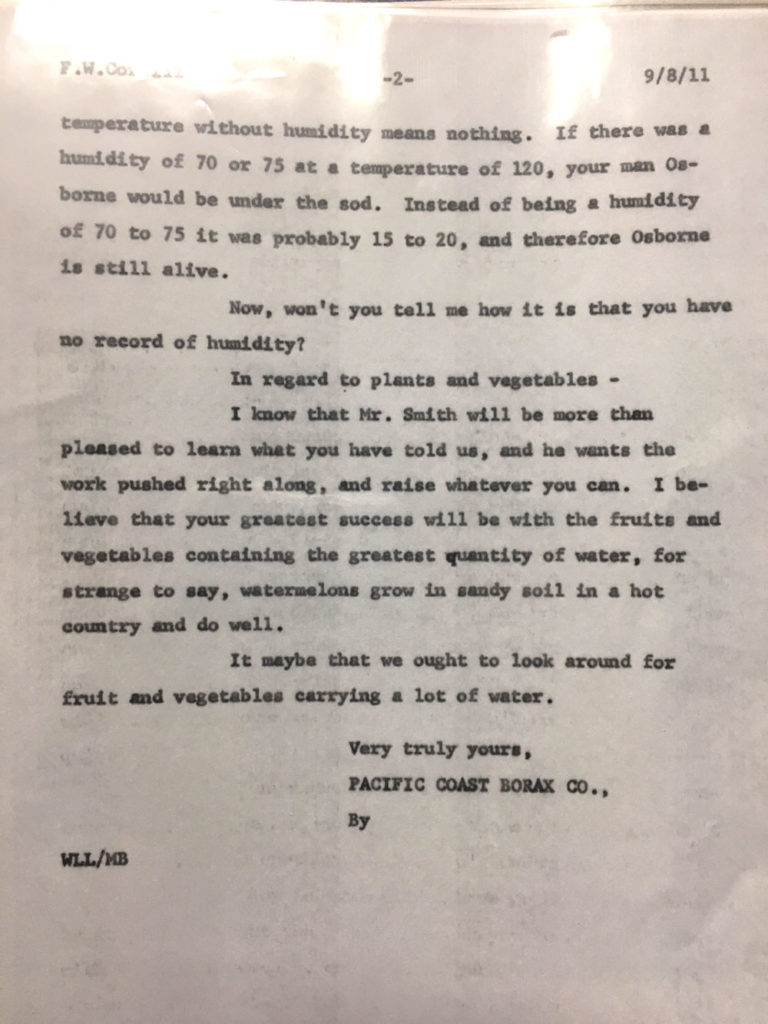

Locke quickly replied to Corkill with this letter dated September 8, 1911:

Locke says that he does not understand the “set max” temperature. (The “set max” is the temperature indicated on the maximum thermometer after it is reset at the official observation time. The time of observation was 5 p.m. The minimum thermometer, reset at the same time, should read the same or within a degree of the set max.) Locke is also a bit incredulous that there is no humidity information, and he instructs Corkill to get to work on this. Wet bulb and dry bulb thermometers are needed!

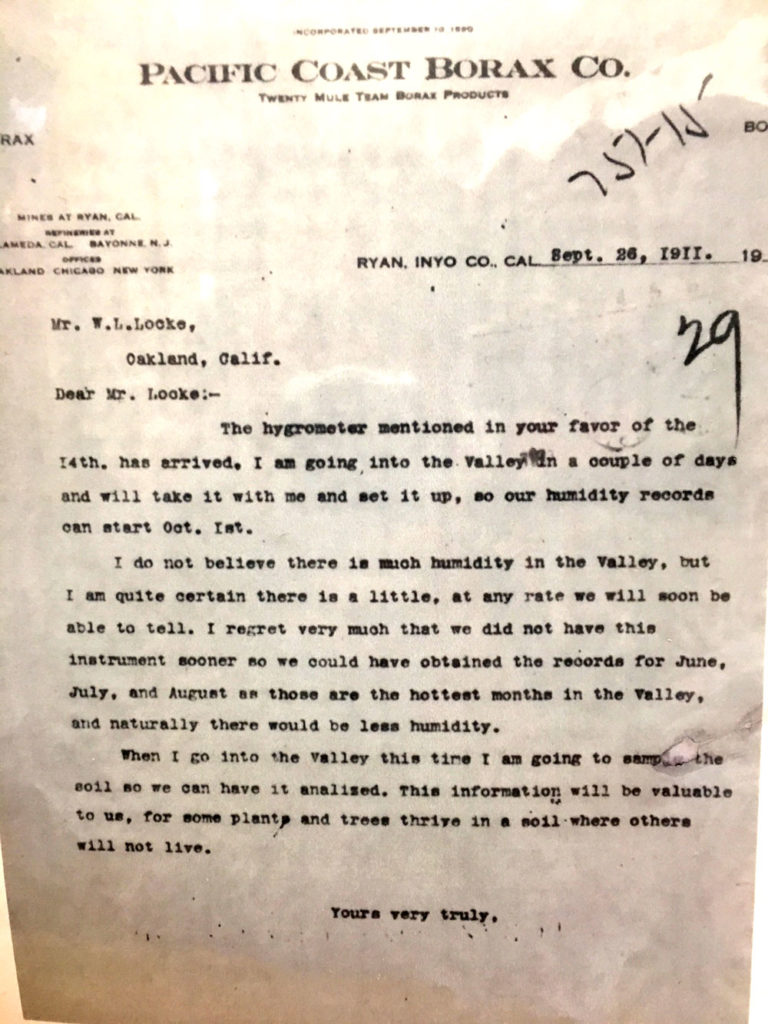

Corkill worked quickly on the humidity issue, and by September 26, 1911, he had a hygrometer in his possession at Ryan (see letter to Locke, above). He would have the instrument up and running at Greenland Ranch by October 1. Chances are good that a psychrometer and its dry and wet-bulb thermometers was also part of the shipment. (This instrument is mentioned by Corkill in a letter several years later.)

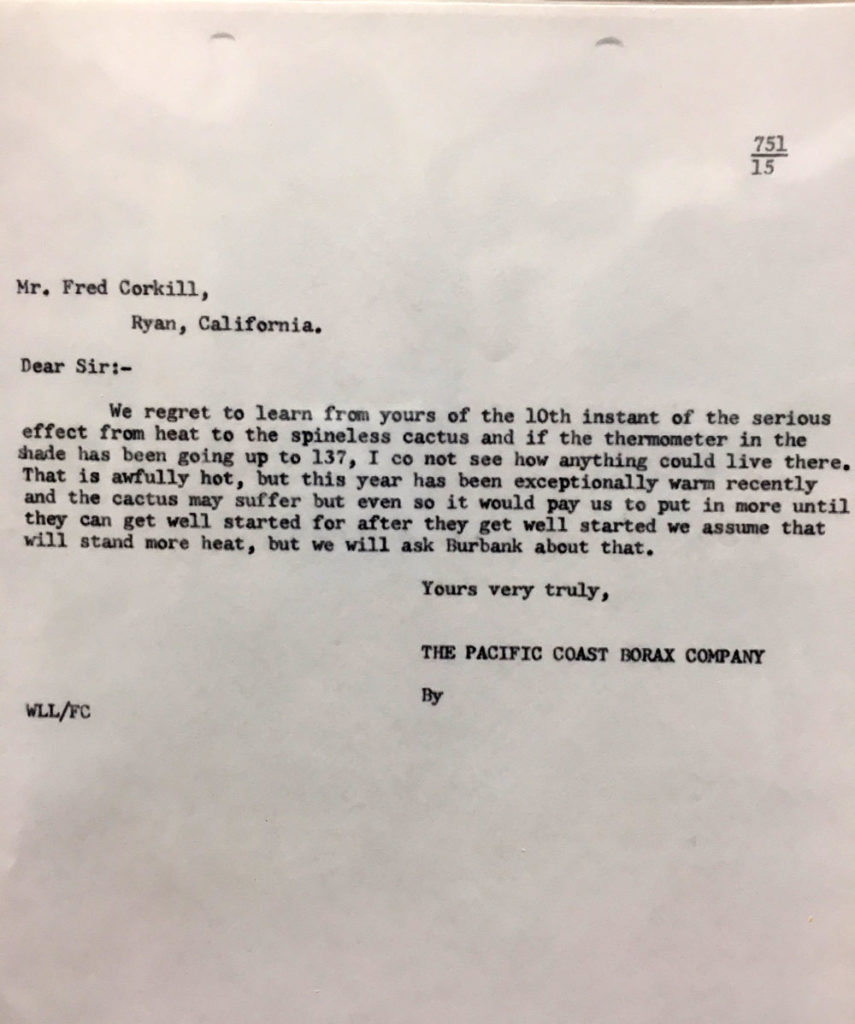

The letter above, from Locke to Corkill, is not dated (it was between the letters from 1911 and 1913 in the archive folder). It may be from the summer of 1913, when the 134F temperature record was set. Locke references previous correspondence by Corkill which mentions temperatures in the shade as high as 137F. The hot weather was not kind to the cactus at the ranch. Interestingly, and perhaps strangely, it is the temperature reading from the thermometer in the shade (and under the veranda of the house, presumably) which is used to describe conditions, and NOT the official and standardized readings from the USWB instruments. Was Corkill more inclined to trust the “house” thermometer versus the official USWB instruments? This would be somewhat strange, given Corkill’s familiarity with official instrumentation as observer at Candelaria, Nevada.

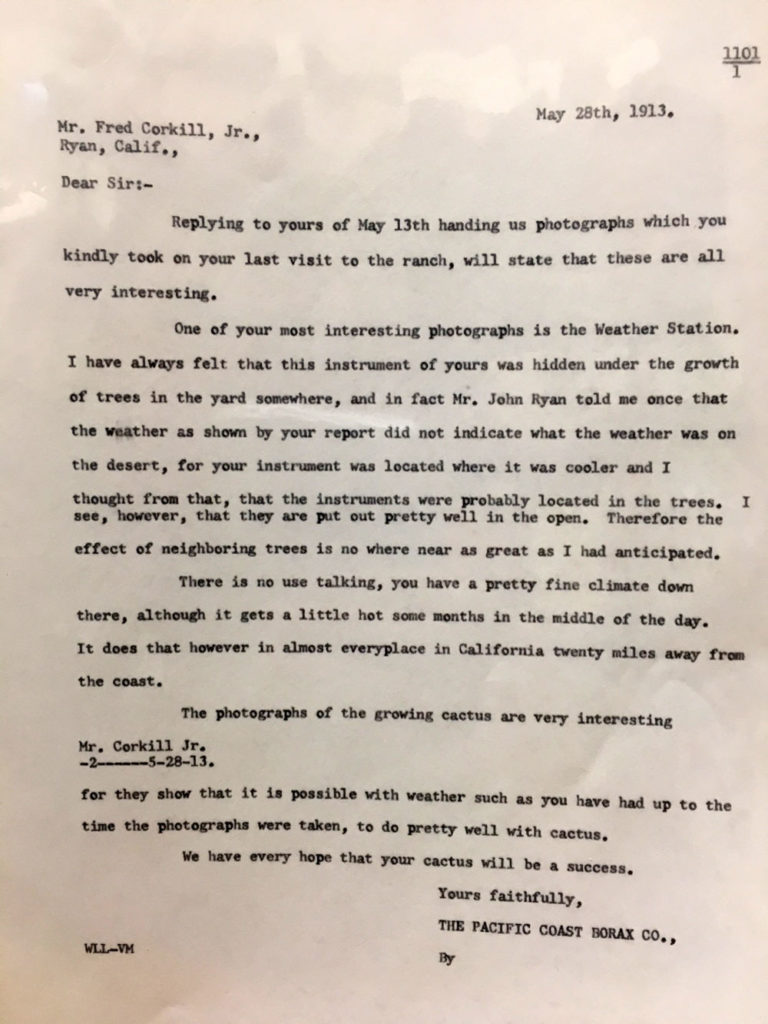

The letter of May 28, 1913 (above) is from William Locke, in reply to earlier correspondence from Corkill which included photographs of Greenland Ranch and the weather station. Two years into the station’s record, and Locke was aware that the thermometer shelter “was located where it was cooler.” He apparently was a little surprised that, given the coolish readings, the instrumentation was not in the shade of trees, but well out into the open. Prior to the hot summer of 1913, those familiar with Greenland Ranch and its weather station knew that it was not providing maximum temperatures which represented conditions “on the desert,” as John Ryan described to Locke.

The Siting of the Greenland Ranch Instruments and Photos

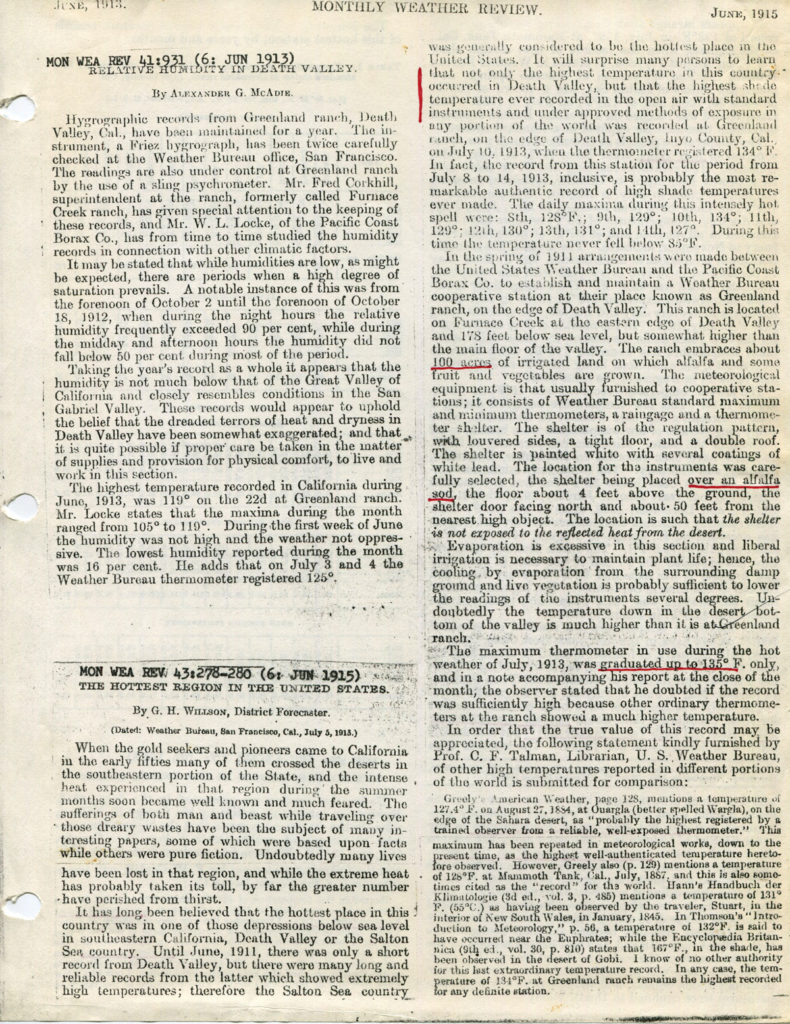

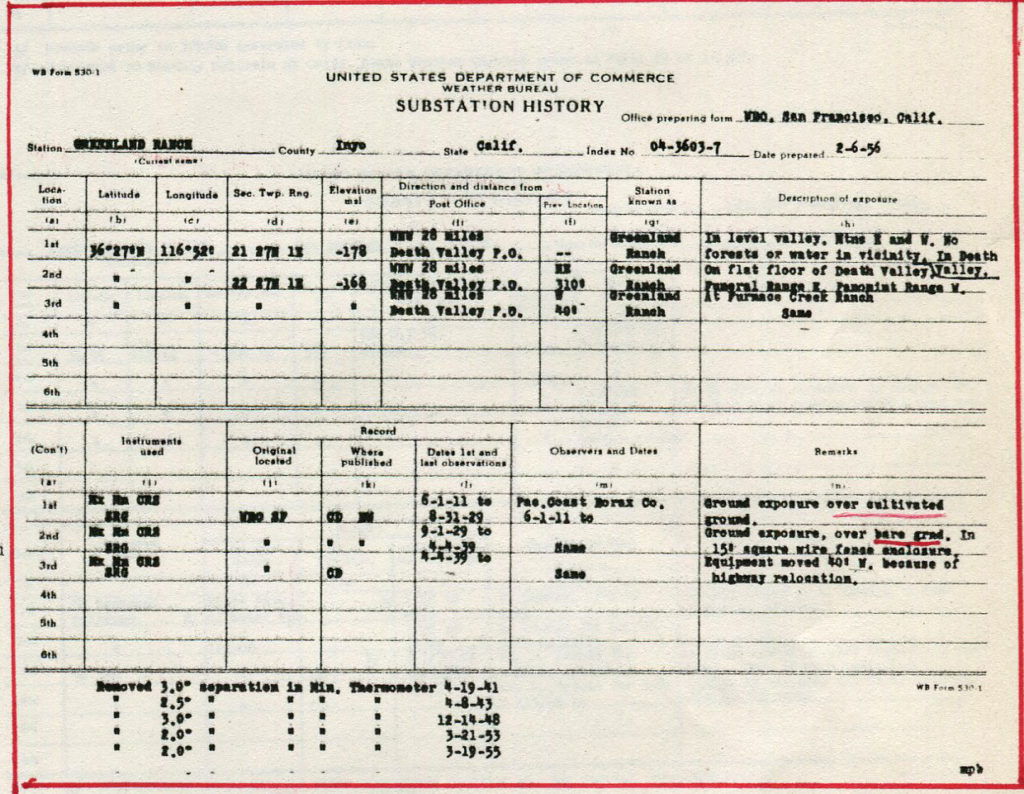

Greenland Ranch’s “substation history” indicates that the thermometer shelter was sited above cultivated ground, and this is emphasized by Willson in his Monthly Weather Review article in 1915 (see Part One of this study). The oft-irrigated and moist cropland below and around the thermometer shelter resulted in relatively conservative maximum temperature reports at Greenland Ranch in its first two summers.

The panoramic photograph above was taken in 1916 (according to the caption at the top — were those automobile models around in 1916?), and shows the Greenland Ranch weather station in the middle foreground. The view is to the north, with the ranch buildings and trees in the middle distance. On the west/left side is cultivated land, apparently, and uncultivated land is on the right/east side. The ground surface inside of the fenced enclosure appears much darker than the ground in the immediate vicinity, and is likely grass or alfalfa: the “cultivated ground” which Willson mentioned. A zoomed-in version of the above photo is provided below, and shows the grassy station environment a bit better. Click to enlarge.

In the aerial image of Greenland Ranch provided above, the view is to the southeast, with the mouth of Furnace Creek Wash and Furnace Creek Inn in the upper left. A road from the inn and wash area to the ranch is very apparent. (This road was abandoned later when a new highway was constructed.) Nearby, dark vegetation lines a trench (or irrigation ditch) which extends from the inn to the ranch. The ranch buildings and the weather station were a short distance inside of the vegetation-lined eastern boundary of the ranch, near the point where the old road and irrigation ditch joined the ranch. Note that the automobiles in the 1916 panoramic shot (above the aerial image) are coming off of a road that accesses the ranch from the east, quite close to the weather station. This is likely the road from Furnace Creek Inn and Furnace Creek Wash that is visible in the aerial photo. This is the road that the desert traveller would take to Ryan and Death Valley Junction. The Greenland Ranch weather station and the main ranch buildings were on the eastern edge of the ranch and its 40 acres of well-irrigated crops. Wind from the south would straddle the boundary of the ranch as it approached the thermometer shelter. A wind from the southwest or west would be cooled above the alfalfa field as it approached the station. A wind from the east or southeast would be much less impacted, if at all, by the moist environment of the ranch before reaching the station. The substation history indicates that the weather instruments were moved 310 feet to the northeast in August, 1929. This would put the instruments a bit east or southeast of those tall palm trees on the right side of the panoramic photo. On April 4th, 1939, the instruments were moved again, this time 40 feet to the west, to accommodate the relocation of the highway, according to the substation history. Since this new highway is not shown in the aerial photograph above, the image was taken sometime between about 1927 (when Furnace Creek Inn was built) and 1939. More info below on the later station moves…but first we need to examine other early images of the Greenland Ranch weather station, and try to explain WHY, HOW and WHEN the ground cover beneath the thermometer shelter changed from moist and grassy to dry and barren. Let’s again provide the MWR article by George Willson (of the USWB in San Francisco) who emphasized the importance of the ground cover around the and beneath the weather station:

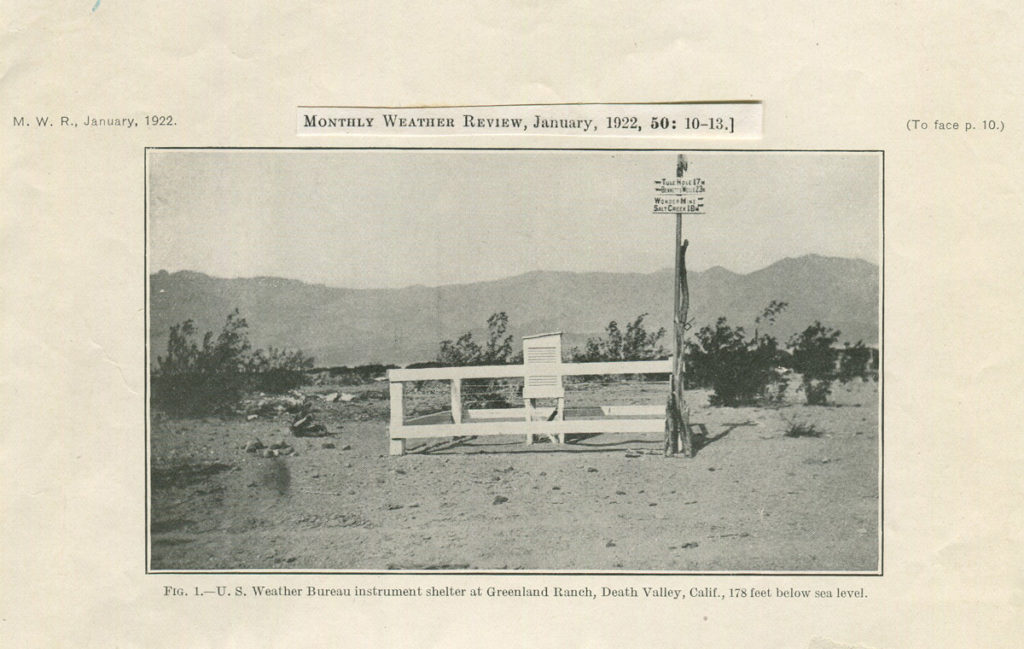

A photograph of the Greenland Ranch station (above) appeared in the January, 1922, edition of Monthly Weather Review. The exact date of the photograph is unknown, and here we will call it the “circa 1920 MWR” photo. The front door (taller side) of thermometer shelters was always positioned facing north, so north is towards the right and the view is to the west in this image.

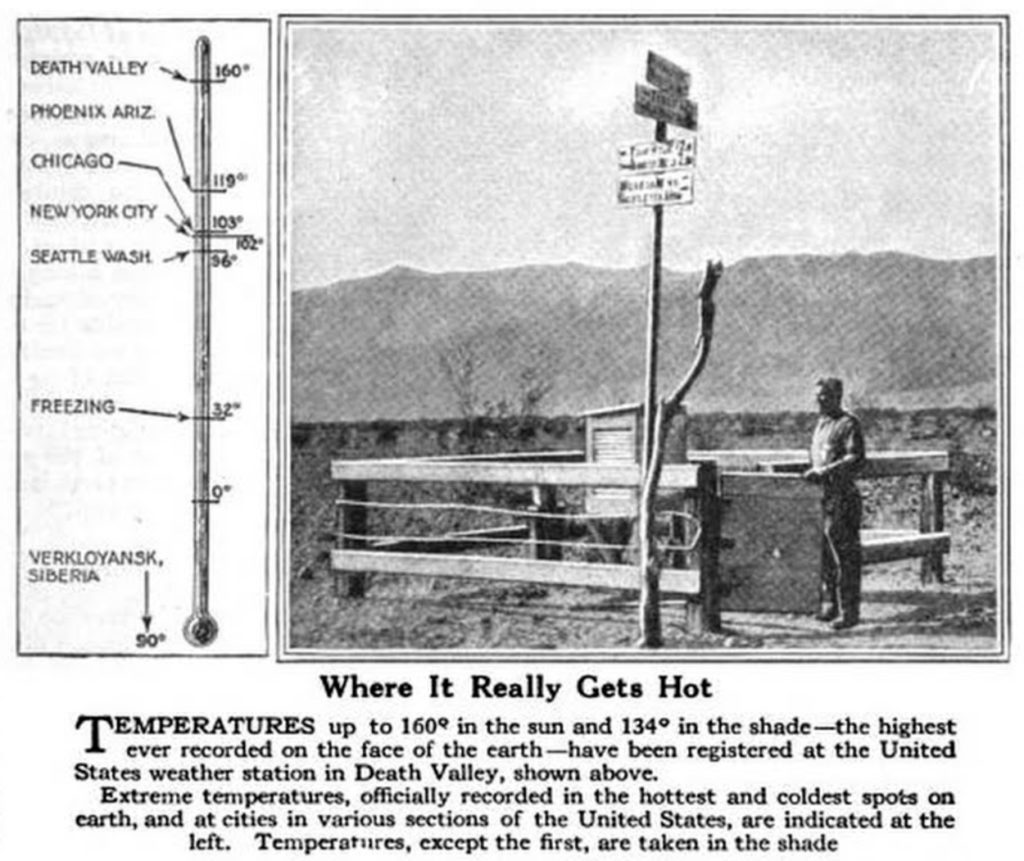

The image and captions above appeared in the September 1922 issue of Popular Science Monthly. The date of the photograph is not known, but the individual, or observer, appears to be Oscar Denton. Denton was observer until about August, 1920. It is likely that this photograph in Popular Science Monthly was taken from about 1918 to 1920. The view is towards the west-southwest, and the barren desert landscape is similar to that in the circa 1920 MWR image. (Note: the Popular Science Monthly article was by J.E. Hogg. A second article by Hogg, in the Wide World Magazine, involves Denton and a couple of visitors to the ranch.)

Obviously, there are important differences apparent between the circa 1916 panoramic photograph and these two from circa 1920. It looks like barren desert has replaced the alfalfa field which was just west of the shelter (as evident in the image from 1916). There is bare ground in the station enclosure circa 1920, whereas there was grass or alfalfa in 1916. There is no documentation that the station was moved between 1911 and 1920, but something changed. Denton may have stopped growing alfalfa just west of the station, and stopped watering the grass in the fenced perimeter, perhaps to promote hotter temperature readings. But there is no evidence of old cropland to the west of the instrumentation in the circa 1920 images. The native desert plants would probably not already be that large by 1920, and the desert surface would not be so original-looking so quickly. A more plausible explanation is that Denton moved the weather station farther from the cooling influence of the irrigated alfalfa fields. Perhaps Denton moved everything to the south, 600 feet or more, towards the extreme southeastern corner of Greenland Ranch. If Denton did indeed move the station, the images above suggest that the move occurred sometime from 1916 to 1920.

Besides the ground-cover change to the west of the instrumentation, there are some other differences from 1916 to circa 1920 which suggest that the station was moved. Examine the rain gage in the 1916 image. It is to the west or southwest of the shelter, and seems to be supported by two wooden slats which diagonal across the southwestern corner of the wooden fence. The circa 1920 MWR image shows no evidence of a rain gage or the support slats, though the “edge-on” view may hide some of these. The circa 1920 image from Popular Science Monthly, with Denton, shows a rain gage just east or southeast of the shelter, and no evidence of the support slats. The top of the gage is lower than the perimeter fence, whereas it was above the fence in the 1916 image. The top of the rain gage appears a little too close to the shelter, which would affect the catch if the wind and rain were from the west or northwest. A USWB employee would, hopefully, not “okay” such a close placement of the rain gage to the thermometer shelter. The gage was probably placed there (too close to the shelter) by Denton. The 1916 image shows fence posts running north-south on the west side of the station, and the circa 1920 pictures do not show a fence. The weather station’s perimeter fence was not painted in the 1916 image, but is painted white in the circa 1920 photos. The evidence appears to be fairly strong that the Greenland Ranch station was moved to a different spot between 1916 and 1920. I suspect that Denton moved the instruments to a locale which was much less influenced by the cooling effects of the ranch’s farmland. He did this so that summer maximum temperature measurements would be higher.

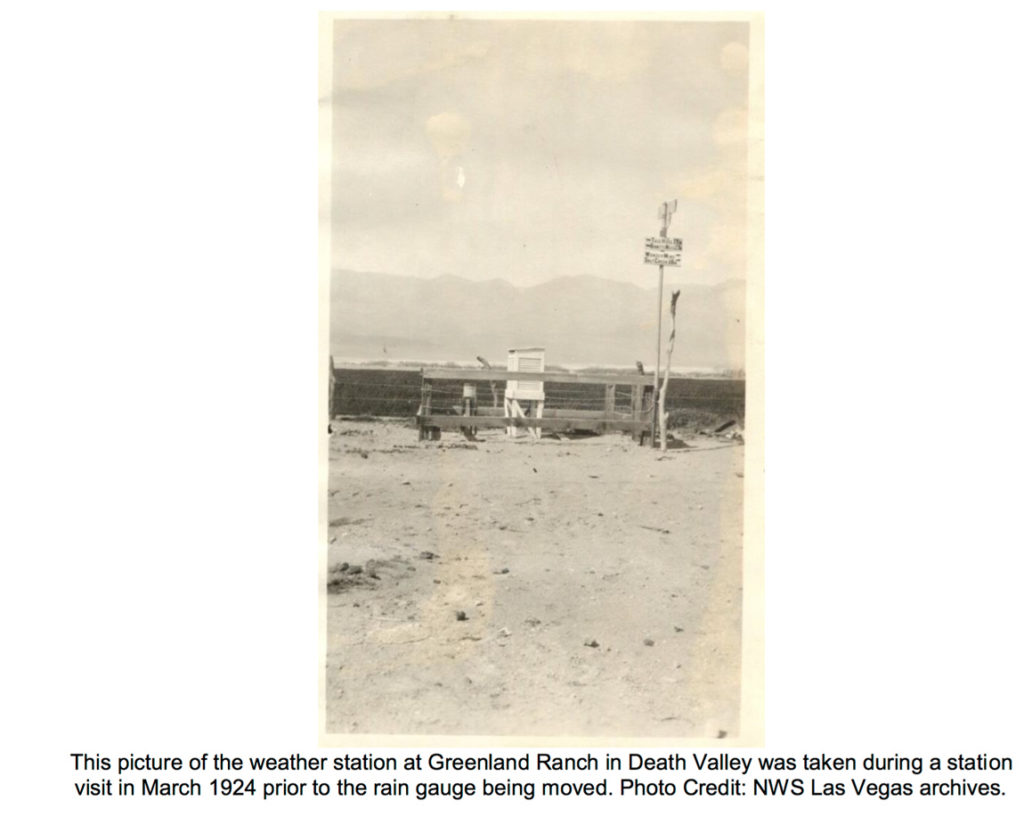

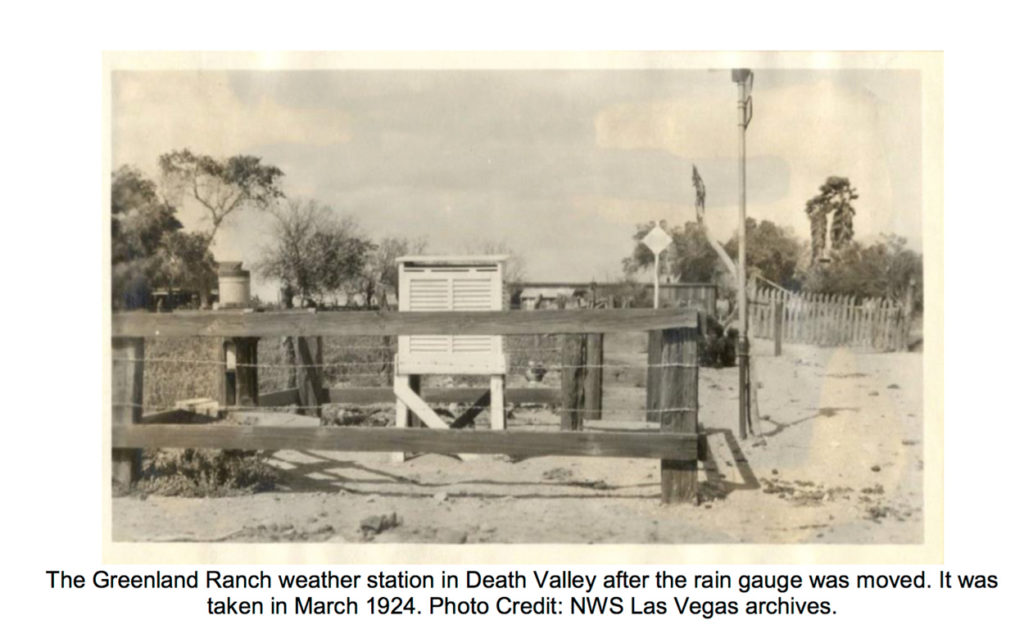

The image above, and the next two below, are from Stachelski’s online “History of Weather Observations” writeup regarding Greenland Ranch and Death Valley, on the NWS Las Vegas web site. The captions by Stachelski are included, and the photo credit is the “NWS Las Vegas archives” in each instance. The above image from 1924 again shows farmland just west of the weather station. The view is to the west.

The image above is from the same visit in March, 1924, by the United States Weather Bureau (presumably). The view is to the north. The rain gage is again supported in part by the diagonal wooden slats on the southwestern corner of the enclosure. There appears to be cultivated land just west of the instruments, but there is no grass inside of the fenced enclosure. As in the images circa 1920, the tall sign post and a funky-looking stick are near the gate to the station. Fence posts are again along the western side of the station. This looks like the spot where the station was in the 1916 image, but with bare ground inside of the fenced enclosure. Note that the rain gage was repositioned between the times of the photographs, according to the captions. The wooden fence shows no signs of white paint. The circa 1920 MWR image shows a fence painted white.

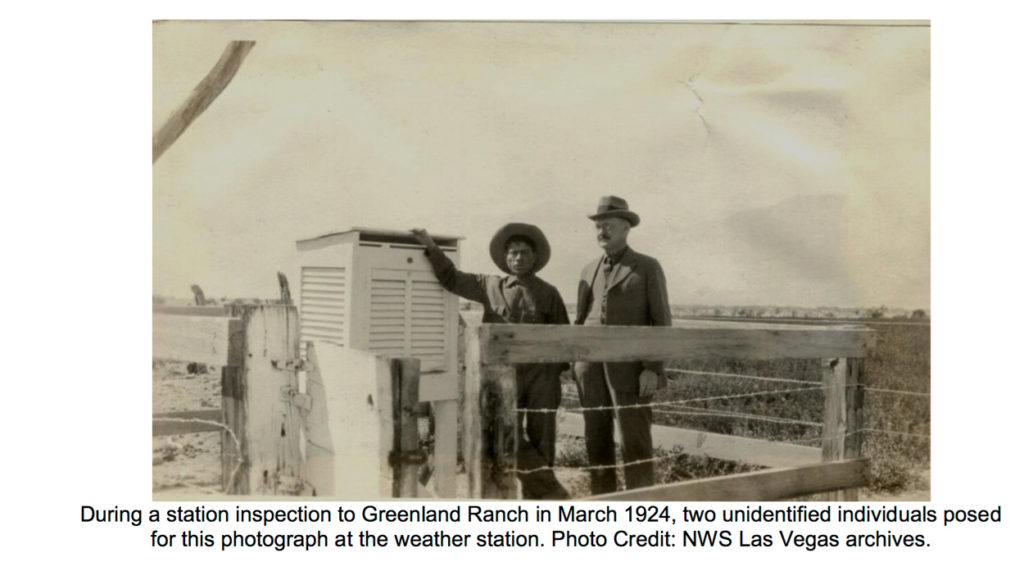

The USWB’s “inspection” of Greenland Ranch provides us with a photograph of (presumably) the station observer in 1924: Victoriano Cebellos. The other “unidentified” individual is probably the USWB inspector, out of the San Francisco office, perhaps Edward Hall Bowie. Bowie is on the far left side in the image below. (This image is from “History of Weather Observations, San Francisco, California, 1844-1948, by Glen Connor. George H. Willson is also pictured.)

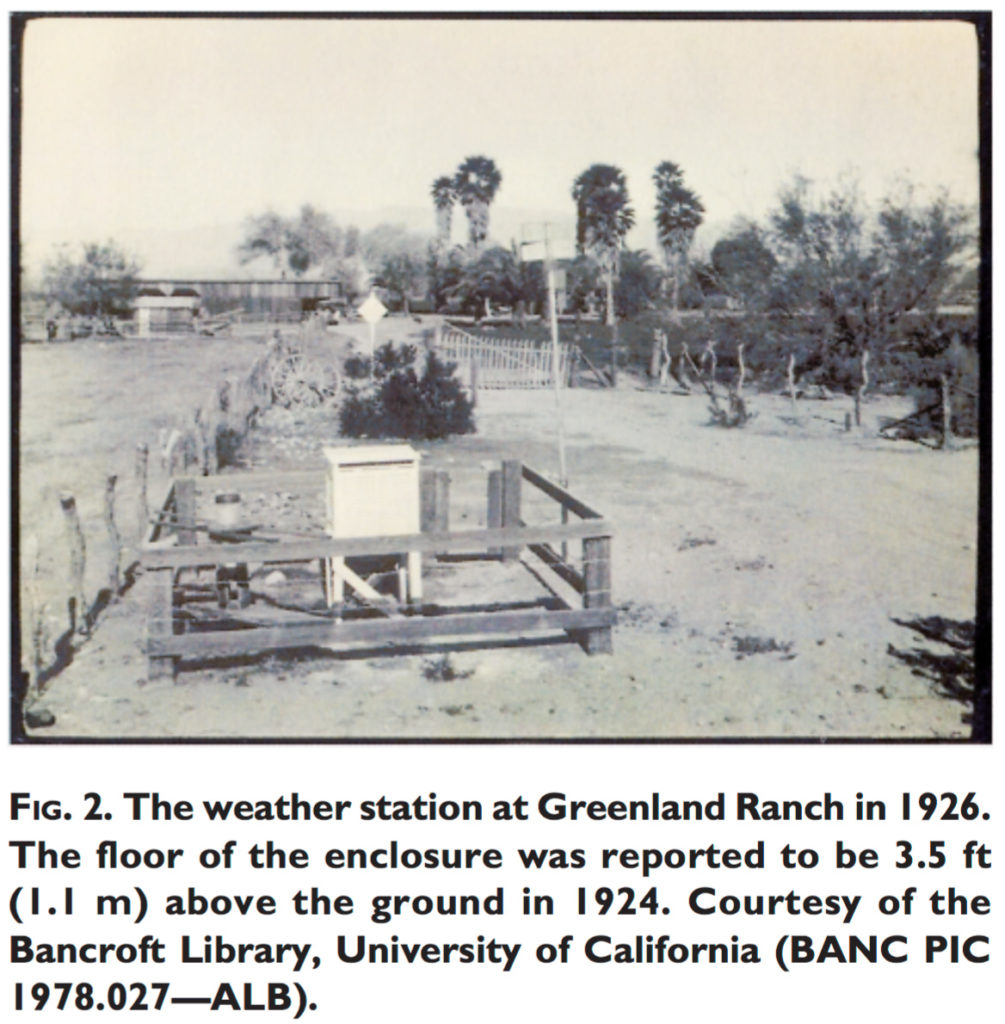

The image above from 1926 is from the BAMS Death Valley Climate article by Roof and Callagan, with credit to the Bancroft Library, University of California. The view is, again, to the north. The ground beneath the shelter is bare, and the field on the west side appears unplanted and bone dry. The rain gage and the diagonal wooden slats are easily visible. The wooden enclosure is not painted.

The images from 1924 and 1926 appear to show that the Greenland Ranch instruments were (back) at its original location, along the eastern edge of the “cultivated land” (or the alfalfa field). The natural desert vegetation which is nearby on the west side of the instrumentation circa 1920 is NOT apparent in the 1924 and 1926 images. If it is assumed that Denton moved the station from its original site sometime before his departure in 1920, then the station was moved back to its original site sometime between about August 1920 and March 1924, while Victor Cebellos was the observer.

It is not clear if Denton fashioned a new wooden enclosure for the station or if he used the original one. Since it appears that the diagonal wooden slats for the rain gage were not part of the “circa 1920” station enclosure, and since the fence of the “circa 1920” station was painted white, then perhaps Denton did indeed make a second fenced enclosure at a second site. This site was probably quite a bit farther from the ranch house than the original site. Perhaps Cebellos preferred the original location for the station and moved the equipment back. Or, perhaps a company supervisor or a USWB inspector ordered that the instruments be returned to the original location. Cebellos likely moved the instruments back, but put the rain gage in a spot that might have been similar to the spot where Denton had it, with respect to the thermometer shelter. If there were indeed TWO fenced enclosures for the weather instruments, then perhaps Denton moved the thermometer shelter to the more distant “barren” site during the summer, and moved the shelter back to the more convenient original site for the cooler months. It is interesting that in the circa 1920 images, that the rain gage is visible in one but not the other. It would not be a big deal if the shelter and rain gage were at separate locations!

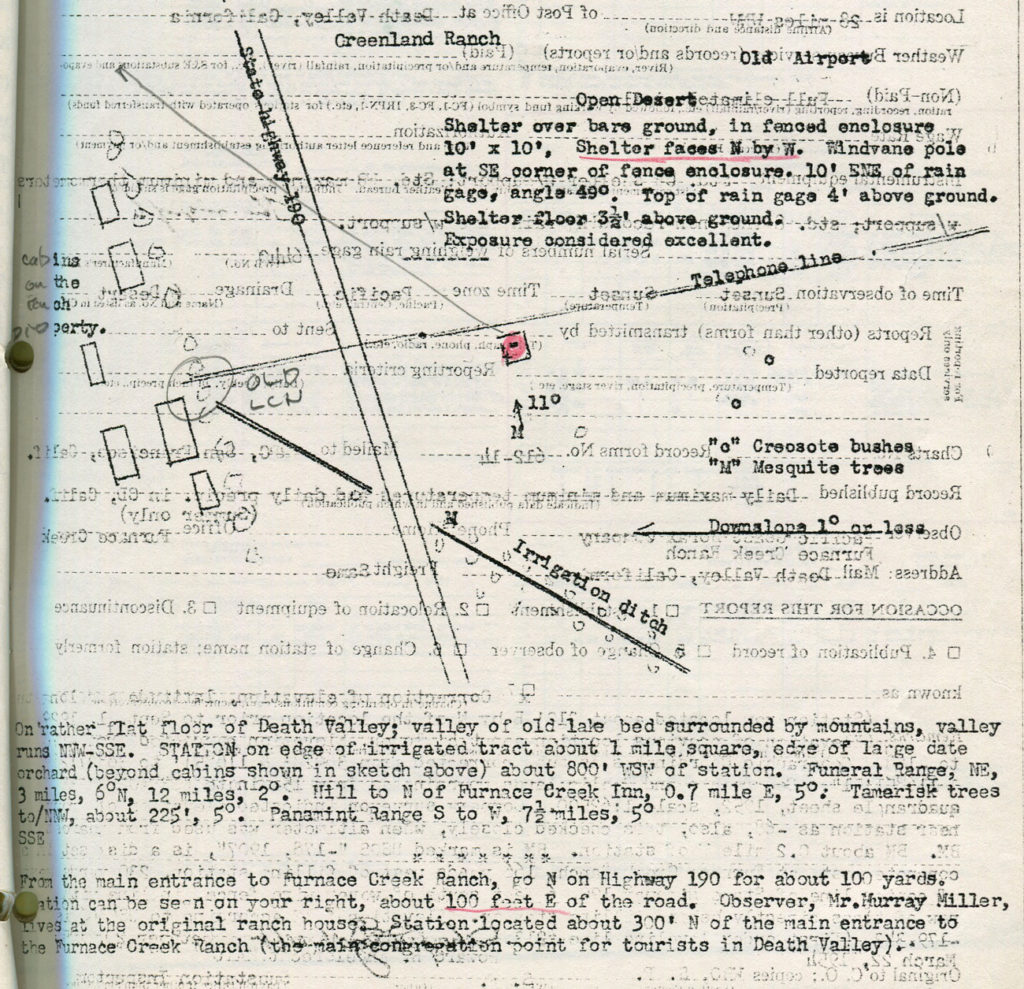

When the USWB inspected the station in 1924, they determined that the rain gage was not exposed as it should be, and it needed to be moved. There are no indications that the USWB was aware of any station movements from 1911 to 1929. The information below is provided by Stachelski:

These detailed notes raise a few questions! Why didn’t the USWB know about the apparent change(s) in the location of the weather station from 1911 to 1924? Or if they did know, why did they not document it? If the rain gage needed to be moved about five feet in 1924, then how did it wind up in a place that was deemed to be unacceptable? How did it wind up in a spot that was not satisfactory if it had been properly sited when the station was first established? Also, was this the first time that the USWB made a visit to Greenland Ranch? Were the initial notes and particulars (provided by Stachelski above) based on a first-hand visit by the USWB shortly after the station opened, or are these based on information provided by Fred Corkill, the ranch superintendent who set up the instrumentation in 1911? This is a good place to drop in the USWB Substation History for Greenland Ranch, through 1955:

So, why are these alleged (alleged by me, but fairly obvious!) station changes and movements between about 1916 and 1924 important? Well, for one, there can be significant differences in the maximum and minimum temperatures measured in the desert and Death Valley depending on the ground cover nearby and/or beneath the shelter. A moist ground will cause cooler temperatures. It is important to know the ground cover beneath the station when comparing temperatures year-to-year and decade-to-decade. And, it is important when comparing Greenland Ranch data to that for other stations in the region. Secondly, the station movement by Denton — which we cannot prove but appears to be the case — shows that he probably had a keen interest in the weather station and the temperatures from it. The station movement by Denton from a relatively cool and moist locale to a hotter and drier spot strongly suggests that he preferred that the station represent more of a true desert environment. It would not be surprising to learn that Denton was disillusioned with cooler readings courtesy of evaporative cooling effects around the original station site.

The early station moves alleged here were likely made without the knowledge of the USWB, and perhaps not even by Denton’s superiors. If Denton did indeed move the station with no authorization, then he must have known that he was acting against protocol. He had no qualms about re-siting an official weather station which had been “carefully selected” by the USWB, as emphasized by Willson. If Denton went to all of this trouble and strayed from standard operating procedure to this extent, then what else might he have done with some daily observations and instrumentation in order to “set things straight?”

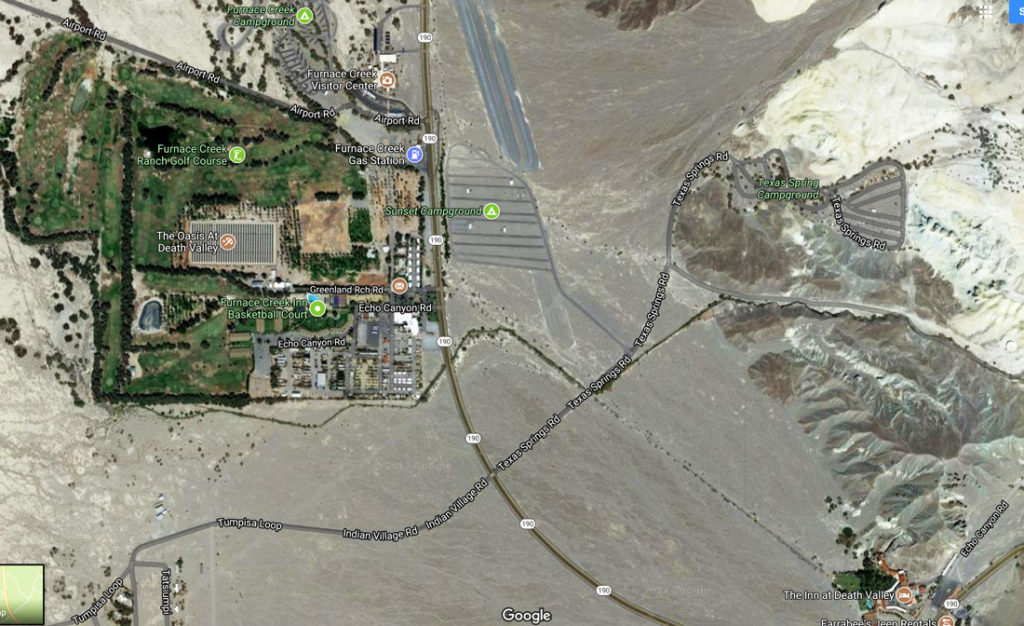

Let’s take a look at a recent satellite picture of the Furnace Creek area.

The satellite image (above, from Google) shows the Furnace Creek Ranch area in 2017. The Furnace Creek Inn is in the lower right. The sharp north-south boundary of the ranch is visible on the east side. Also visible is the lightly vegetated area along the water pipeline/irrigation ditch from the inn to the ranch, as seen in the older aerial photograph. And barely visible is the old dirt road from the inn to the ranch, between the irrigation ditch and Highway 190. Below is a zoomed-in look at the eastern edge of the ranch.

The original ranch buildings were just inside of the eastern border of the ranch, where the irrigation ditch entered the ranch (from the southeast). In the image above, this would be the area with buildings just north of the Death Valley Post Office, maybe 200 feet west of the highway. From the panoramic 1916 photo, it appears that the weather station was about 200 feet south of the ranch buildings — maybe a little farther. That would put the original station site close to where the General Store is. (This would match up with the move to the northeast of 310 feet in 1929, if we move backwards from the station vicinity in the 1950s. The Furnace Creek Ranch resort has been undergoing major renovations in 2017 and 2018, so the old General Store near the front entrance might be somewhere else when you read this.)

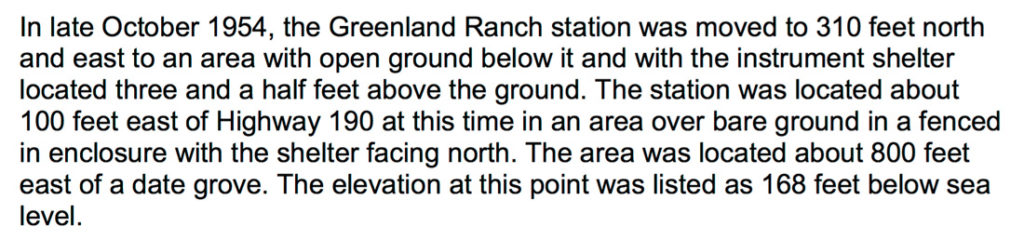

Greenland Ranch Substation History indicates that the station was moved 310 feet to the northeast on September 1, 1929. (Stachelski states that it was moved 310 feet to the north in 1929, but that contradicts the substation history report.) The reason for the move to the northeast is not known, but this would place the station closer to the observer’s residence, and a bit farther from the evaporative cooling effects of the ranch. On April 4th, 1939, the weather station was moved forty feet to the west due to the highway relocation, according to the Substation History. Stachelski reports another move in 1954:

The move of 310 feet in October of 1954 as noted by Stachelski is not documented in the Substation History (which was prepared in 1956 — it notes a minimum thermometer issue in 1955, so a station move in 1954 should, or would have been listed). Since the move in 1929 was also 310 feet to the north and east, it may be that Stachelski is in error on this particular one and the move noted by him in 1954 was in a different direction and distance. Since the shelter was moved 40 feet to the west in 1939 due to the new highway, and since the shelter was about 100 feet east of the highway in the mid-1950s, then perhaps this move in October of 1954 was about 150 to 175 feet to the east.

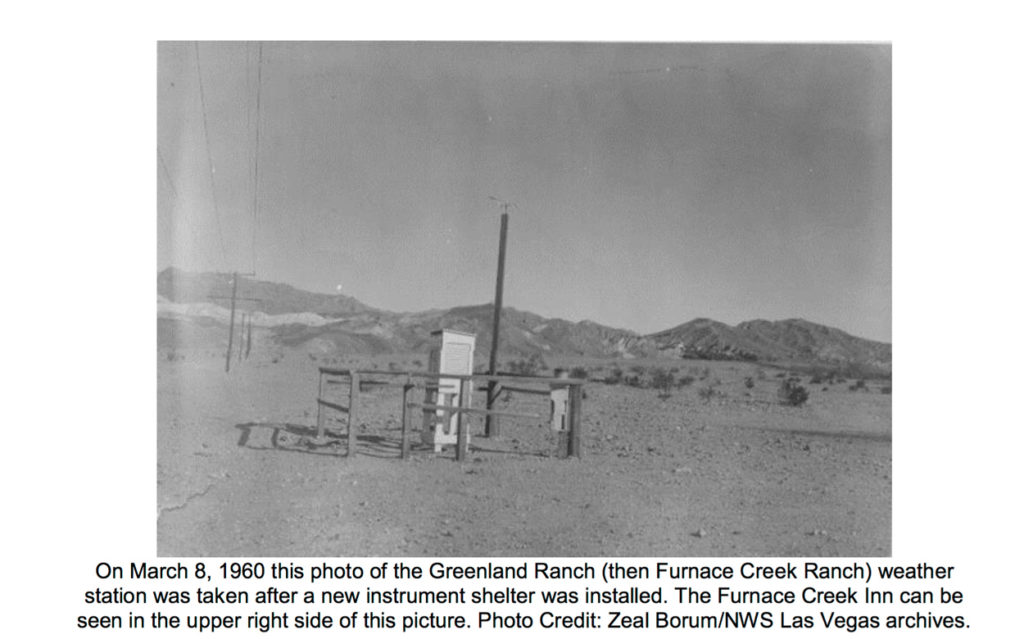

The photo above is from the NWS Las Vegas archives and is taken from Stachelski’s online writeup. The view in this 1960 photo of the Greenland Ranch weather station is towards the east. Highway 190 is a short distance behind the photographer (to the west). The line of utility poles heads east to east-northeastward towards Texas Spring Campground.

The map below shows the location of the Greenland Ranch weather station in the mid 1950s. It was drawn on the back of an official USWB form for the station, and unfortunately the typing on the back shows through the paper a little. This map was prepared by Arnold Court, and he provided a date of October 20, 1954 at the top (not shown here). You can click on it to enlarge it.

Court states that the Greenland Ranch weather station was about 100 yards north of the main resort entrance and about 100 feet east of the highway in 1954. Court’s map shows an older location to the west of the highway, where the irrigation ditch comes up to the ranch buildings. The old location is about 150 feet from the site that is east of the highway. A station move of about 150 feet is not in the documentation.

Stachelski provides some interesting history on the last decade of observing at Greenland Ranch, when the Borax Company transferred observing duties over to the Park Service. The main message: during the 1950s there were issues with the Borax company observer or observers, and the temperature data were not always reliable. Stachelski mentioned other earlier periods where the Greenland Ranch data appeared poor or untrustworthy.

Let’s take some recent satellite pics of Furnace Creek to show my best guess as to the locations of the official weather station since 1911.

“A” is the approximate location of the Greenland Ranch weather station from 1911 to 1929, except for a period of time (based on early images) when the station was apparently more out over open desert.

“B” is the approximate location of the Greenland Ranch weather station from 1929 to 1939, about 310 feet northeast of “A.”

“C” is forty feet west of “B”. This was the location from about 1939 to 1954, presumably. I have yet to see any photos of the weather station at the B and C locations (1929 to 1954).

“D” is the final location for Greenland Ranch, likely moved here in 1954. Court reported that the station was about 100 feet east of a point on Highway 190 that was 300 feet north of the main entrance to the ranch.

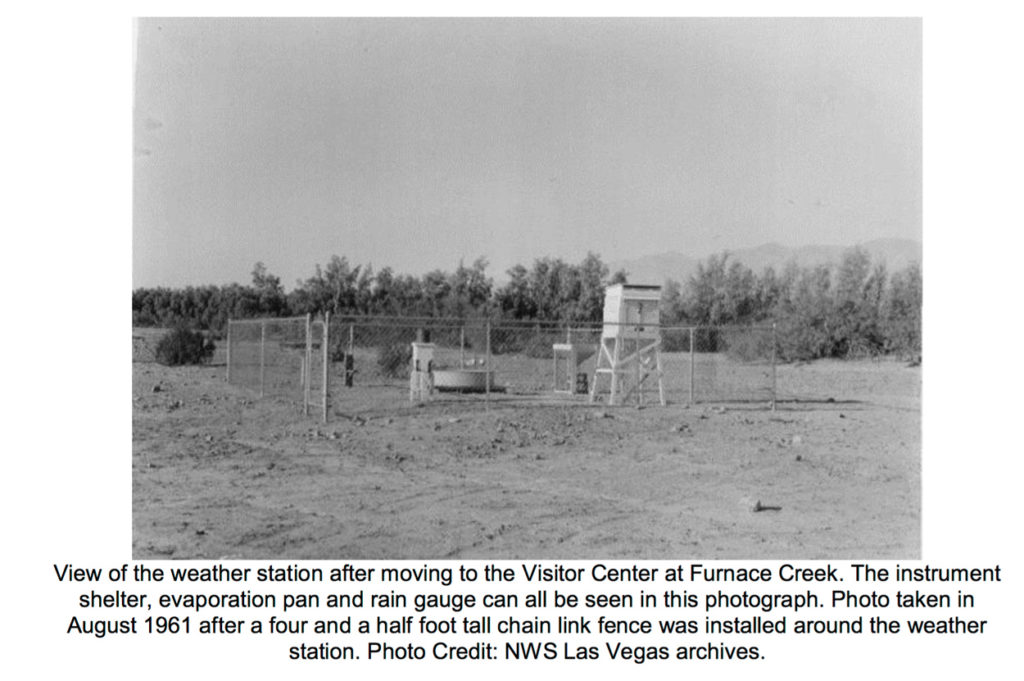

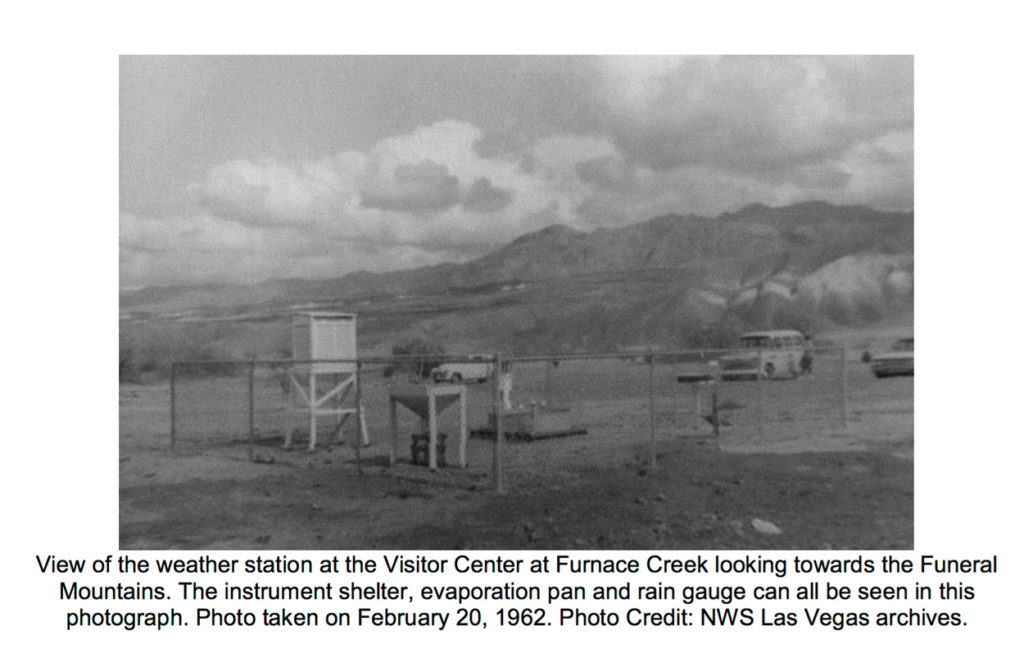

The current Death Valley weather station, just northwest of the National Park Service Visitors Center, is about 2000 feet NNW of the final Greenland Ranch location. It has been at this spot since it was established in the spring of 1961.

Current Death Valley Station Images

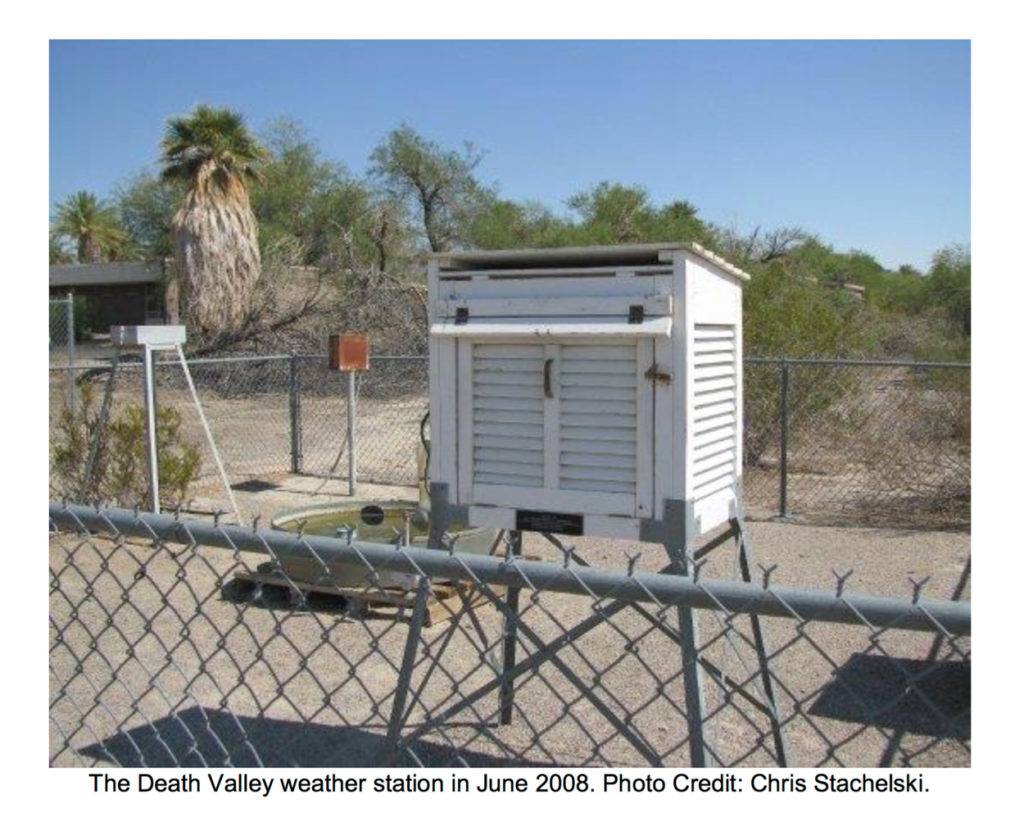

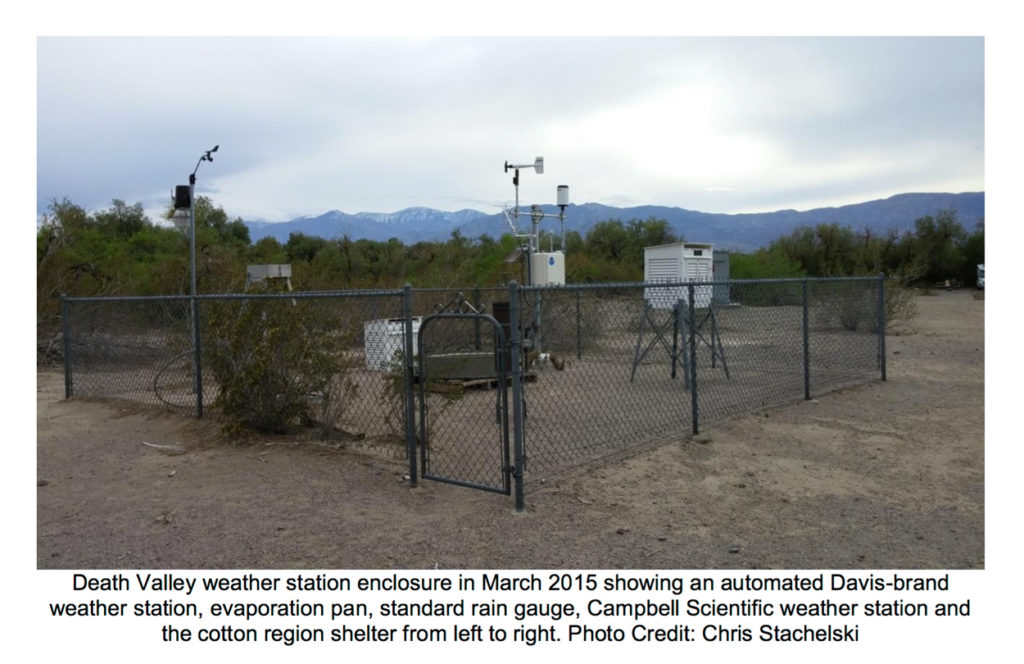

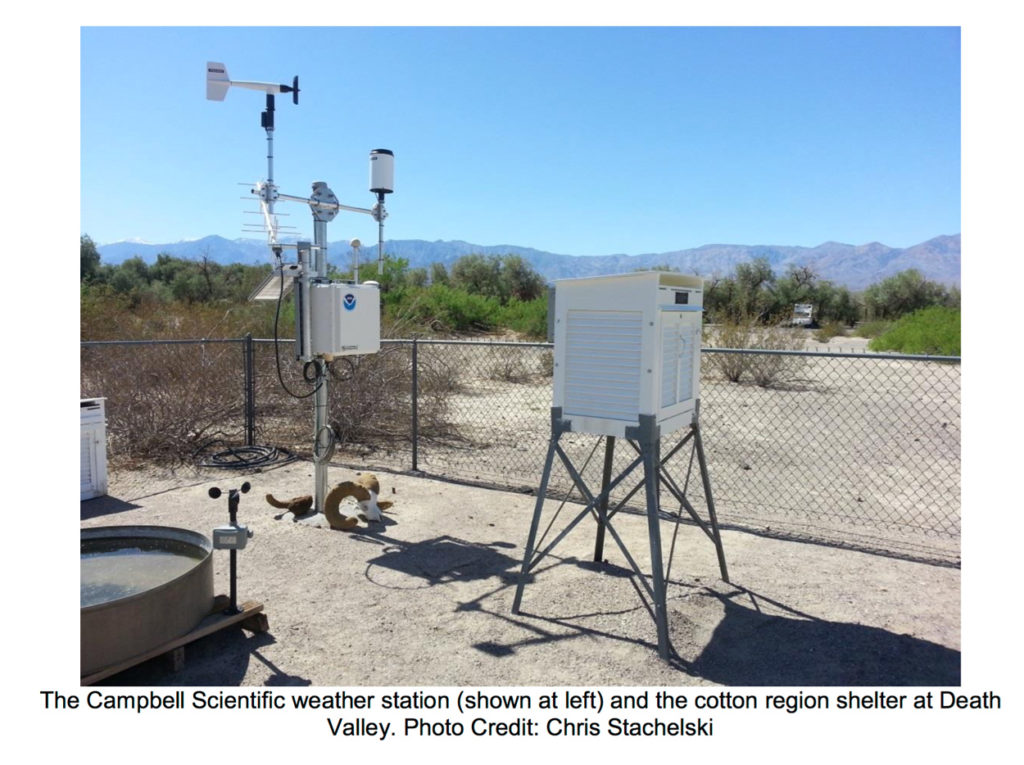

Today, 2017, the official cooperative weather station in Death Valley is the one in the “corral” near the Death Valley National Park Visitors Center. It has been in this same location since 1961, when the Park Service closed the Greenland Ranch and Cow Creek stations.

Above are two views of the “Death Valley” weather station, shortly after opening in April, 1961. These are from the NWS Las Vegas archives, and found in Stachelski’s writeup referenced earlier. The first image is looking to the south-southwest, the second towards the northeast. The ground around the station is bare, and there is some vegetation south of the instrumentation.

Above are three more recent images, from Chris Stachelski, with views to the south-southeast (towards the visitor’s center), towards the west-southwest, and again towards the west-southwest. According to Roof and Callagan, an increase in vegetation to the south of the station is likely the cause of decreased wind movement through the station area during the warm half of the year, compared to the first few decades in this station’s climate history. This would promote warmer maximums in summer at the station. Also helping to promote warmer maximums is 1) a recent change from well-watered lawns to a more natural and drier desert surface around the visitor’s center, and 2) a couple of large mechanical units of some sort (air conditioning units?), which are enclosed by brick walls, nearby to the south of the station.

For more information on the current Death Valley weather station, see my Stormbruiser entry here.

Anthony Watts has provided much research and discussion regarding changes in the Death Valley weather station (and effects on temperature measurement) since the 1990s, including a switch to the electronic MMTS station, and then back to the old-fashioned thermometer shelter, and then to the automatic electronic equipment that is right next to the shelter in the corral. See this link from 2013 and this link from 2018.

More Old Greenland Ranch Photographs

The images below were located in a folder with historic Pacific Coast Borax documents at the museum at Independence.

The image above shows Oscar Denton, ranch foreman and weather observer from 1912 to 1920. Denton is on the left.

East side of the ranch (above)

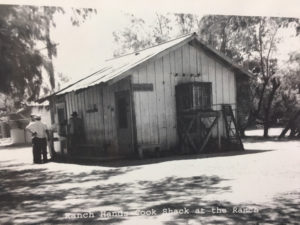

Cook house, date unknown (above)

Ranch house in 1950 (above)

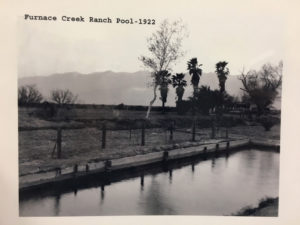

Greenland Ranch pool in 1922 (above)

Greenland Ranch in 1927 (above)

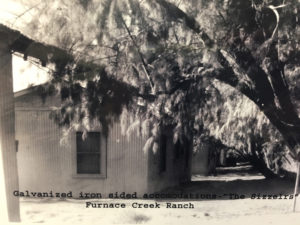

Early accommodations at the ranch, dubbed “The Sizzlers” (above, unknown date)

The image above is in the NP Visitor’s Center. It shows the early Greenland Ranch weather station in the barren/circa 1920 locale. Source is not known.

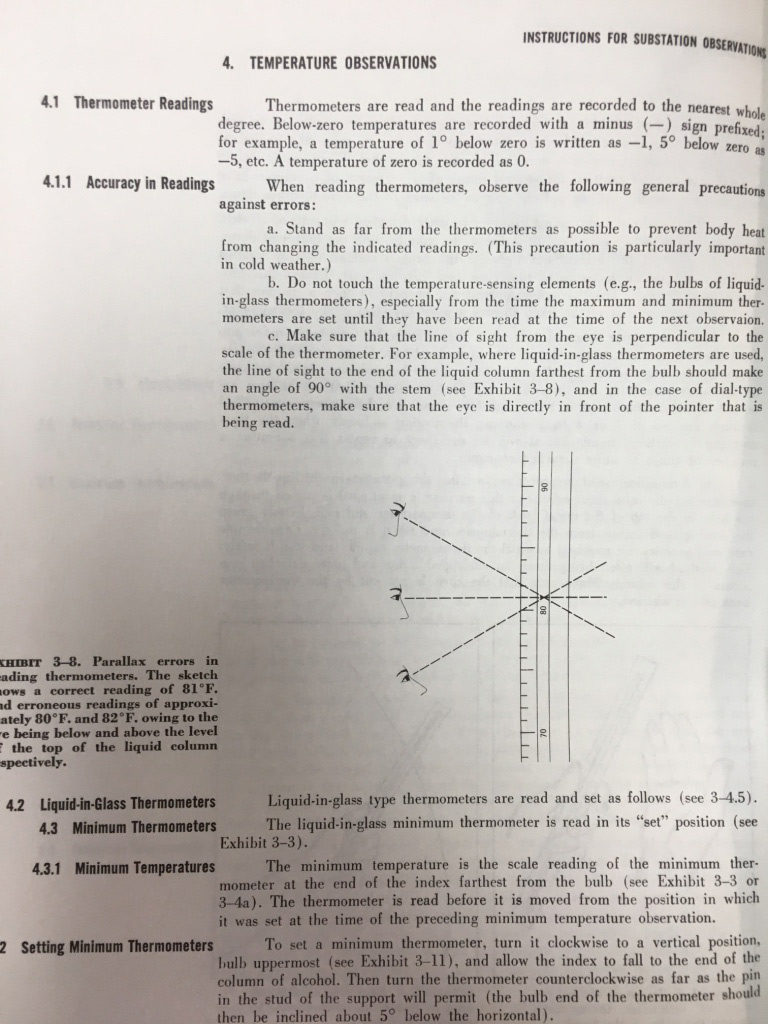

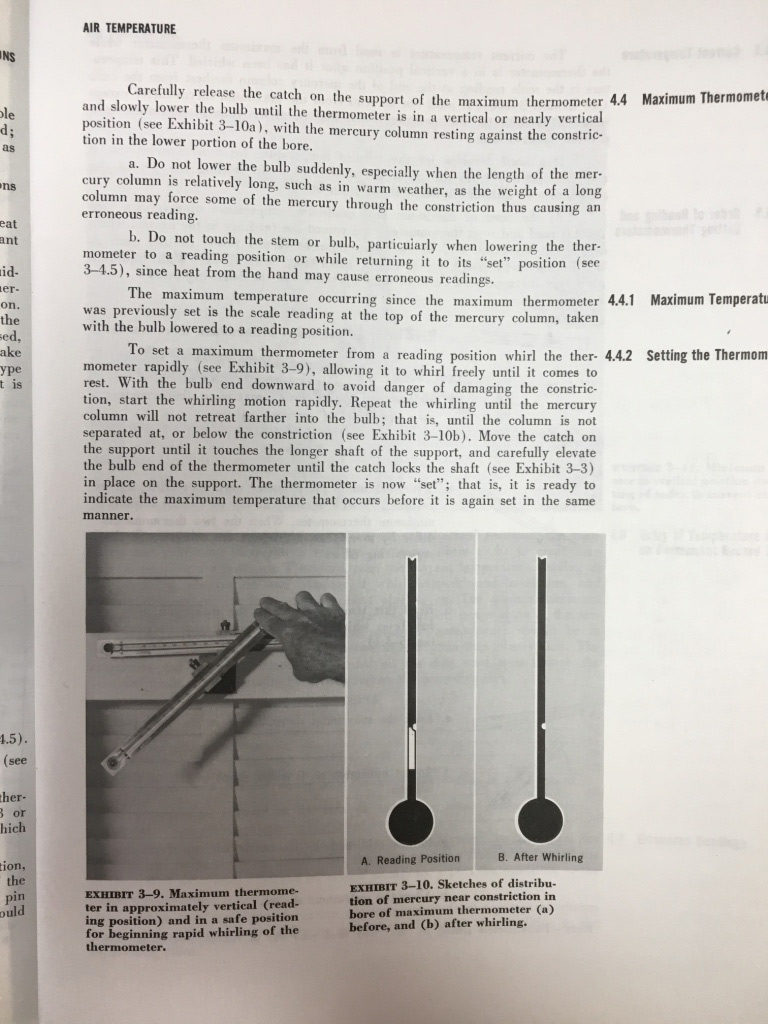

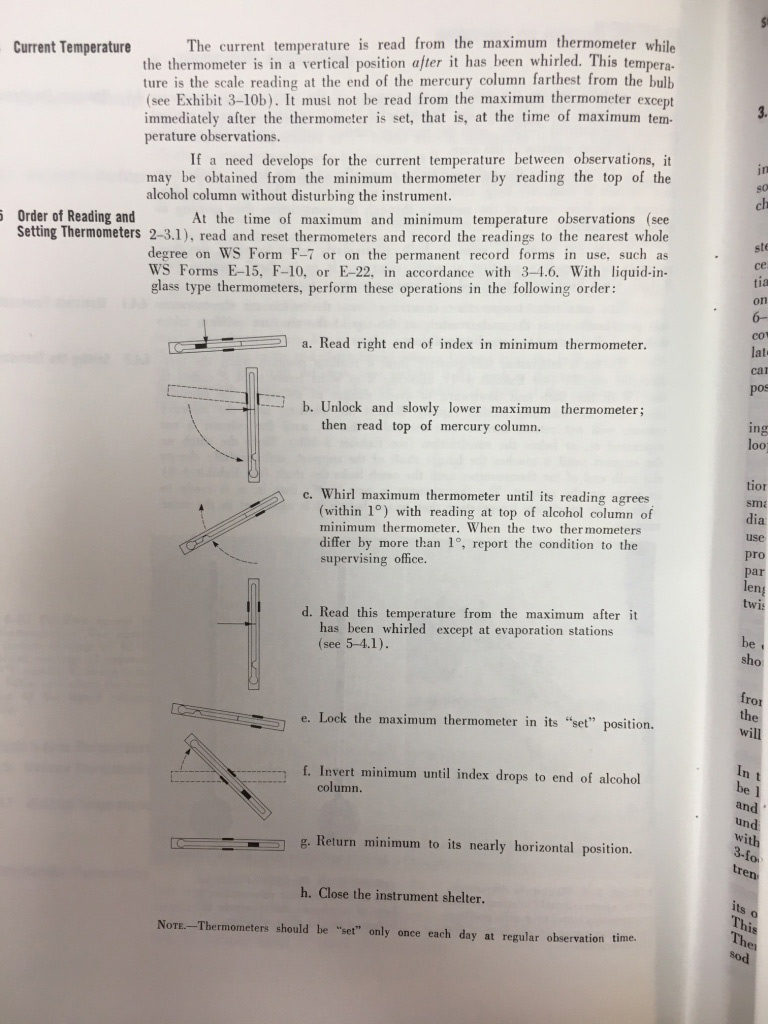

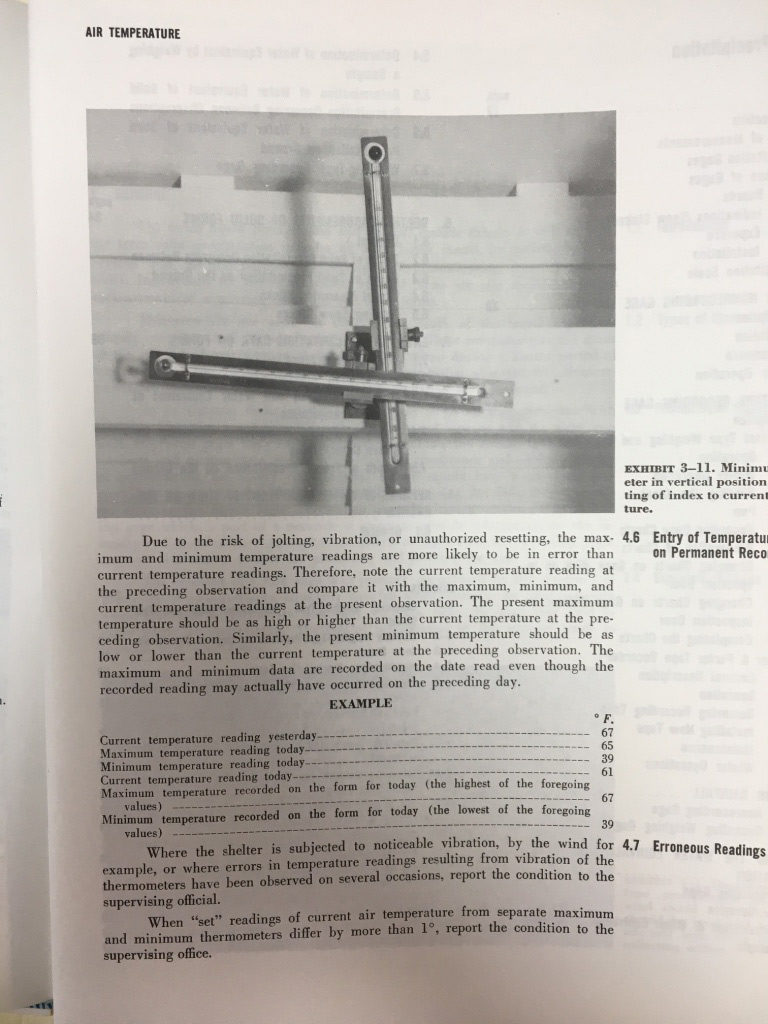

Procedures for Taking the Daily Weather Observation

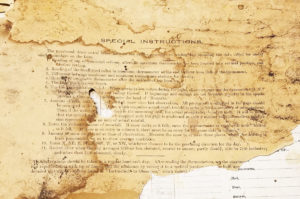

This might be a good place to share the instructions that were provided to the observer by the U.S. Weather Bureau. The daily observation is an easy task, and generally just takes a couple of minutes. There is a particular procedure to follow to make sure that the correct data are entered. The images here include an old tattered sheet (courtesy of the Eastern California Museum in Independence) from the Lone Pine station circa 1920, when Gustave Marsh was the observer. A sheet with a similar set of instructions would, presumably, have been provided to the observers at Greenland Ranch. An updated and more comprehensive pamphlet for the cooperative observer was located in the Death Valley archives. Though the information for the observer is adequate with regard to making proper observations of temperature and precipitation, I think it falls short in explaining what to do in certain instances, such as what to do if an observation is missed or is not at the usual time.

Above is the form of “special instructions” from the Lone Pine cooperative weather station, which operated from about 1904 to 1920.

And above are several pages of the NWS document for the cooperative observers, from 1972. This link is to the NWS Observing Handbook #2, 1989.

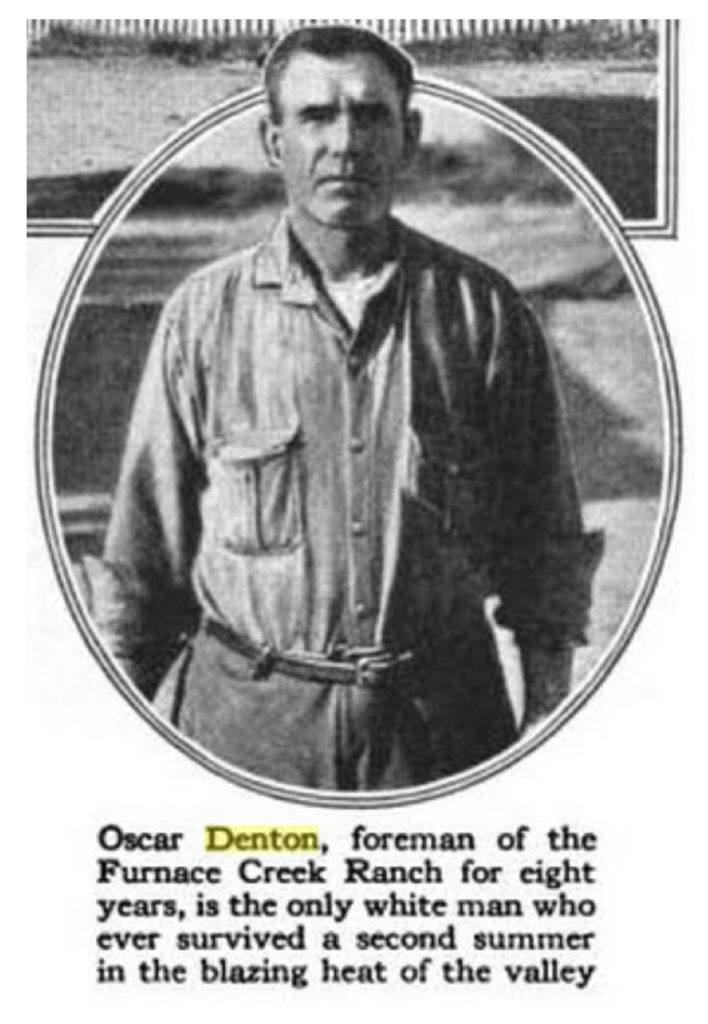

Oscar Denton, weather observer and caretaker at Greenland Ranch from 1912 to 1920

Denton is mentioned in several places in the literature. An image of Denton is included in a Popular Science Monthly article on Death Valley in 1922.

The image on the right, above, is of the Greenland Ranch weather station circa 1920, presumably. The cotton region thermometer shelter and the rain gage are visible inside of the enclosure. The man at the gate is probably Oscar Denton. These images are from Popular Science Monthly magazine. The associated article includes some vivid descriptions of Death Valley and the horrors that await the traveler who dares to visit in summer. Noted beneath the photo of Denton is that he “is the only white man who has survived a second summer of the blazing heat of the valley.” Two previous foremen perished from the heat, apparently, and two others went insane. It is interesting that James Dayton, caretaker of Greenland Ranch for 15 years, receives no credit for surviving summers in Death Valley. Perhaps Dayton spent much of the summers at cooler nearby areas at higher elevations while Denton was “tied” to the ranch in summer in order to take the daily weather observations.

Denton is mentioned in a historic review of Death Valley by Linda Greene, and by author Frank A. Crampton. Here is an excerpt from Greene’s study (Part 2):

(Ranch watchman and caretaker Jimmy) Dayton served as caretaker and foreman of the ranch for about fifteen years, until his death in 1900. By the early years of the next century one Oscar Denton had taken over his duties, and with the help of local Indians was continuing to raise alfalfa and figs. After the turn of the century, the ranch was the scene of increased activity as dozens of prospectors combed the nearby ranges as part of the new southern Nevada mining boom centering around Tonopah and Rhyolite and their environs. The ranch was the resting place where these “desert rats” could lounge beneath the trees and bathe in the ditches while awaiting supplies ordered to be sent to Denton from Death Valley Junction. This was “the place to which everyone went whenever loneliness overcame him and he needed human association and conversation. The old time Death Valley prospectors traveled alone, their burros the only companionship they had. Without Furnace Creek Ranch, Oscar Denton, and the Panamint Indians, Death Valley would have been intolerable.”

The final part above, in quotes, is from Crampton’s book Deep Enough: A Working Stiff in the Western Mine Camps. Also from Crampton’s book: “It was not often that more than one or two of the old timers, prospectors, or desert rats were at the Furnace Creek Ranch at the same time, but Oscar was a good listener, and he passed the latest stories and the best lies to the next to come for the regular clean-up and supplies.”

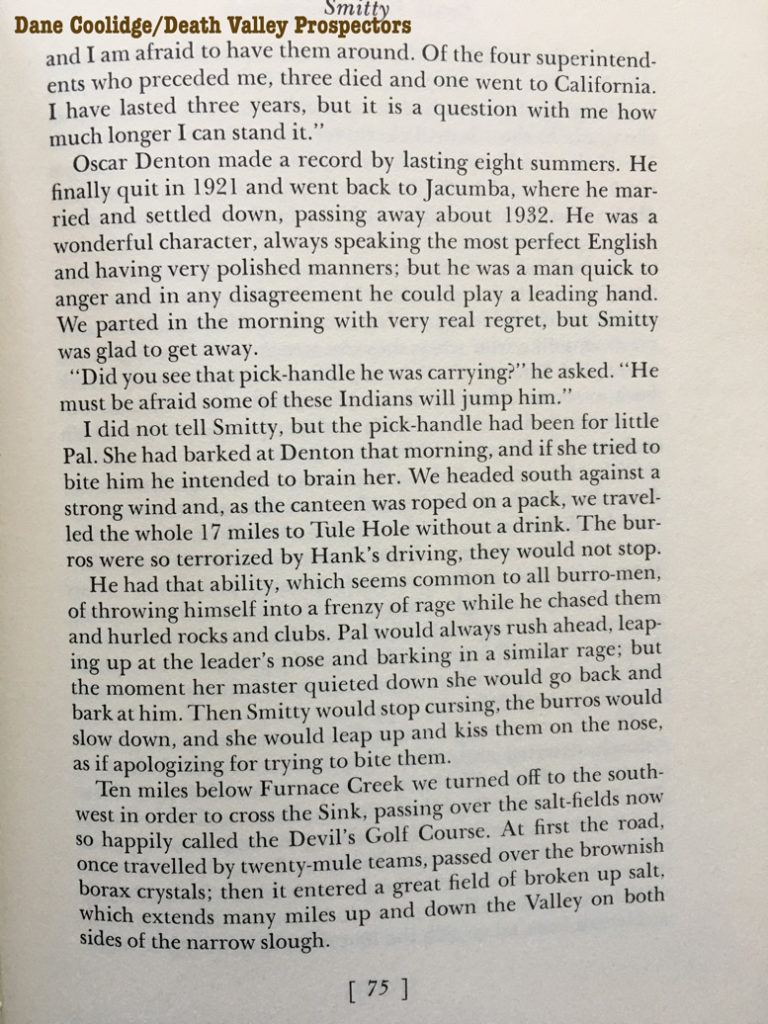

In 1937, “Death Valley Prospectors” by Dane Coolidge was published. Around 1917, Coolidge was guided by Henry “Smitty” Smith from Rhyolite to Furnace Creek, and they met Denton. Coolidge provides some background on Denton, and a fine photograph of Oscar. From “Death Valley Prospectors,” pages 68-75:

Biologist Francis Sumner visited Furnace Creek in 1920, and on page 217 of his “Life History Of An American Naturalist” narrative, he has this to say about Denton:

In charge of Furnace Creek Ranch was an interesting character, Oscar Denton by name, handsome, taciturn, and enigmatic. He was the son of an English army officer by a Spanish mother. Dane Coolidge, in his “Death Valley Prospectors” states that Denton had been obliged to leave Mexico some years earlier, in consequence of a shooting affair in which he had been concerned. He was very suspicious of strangers, and we should not have been allowed to camp on the ranch had not permission been obtained in advance from the officers of the Borax Company.

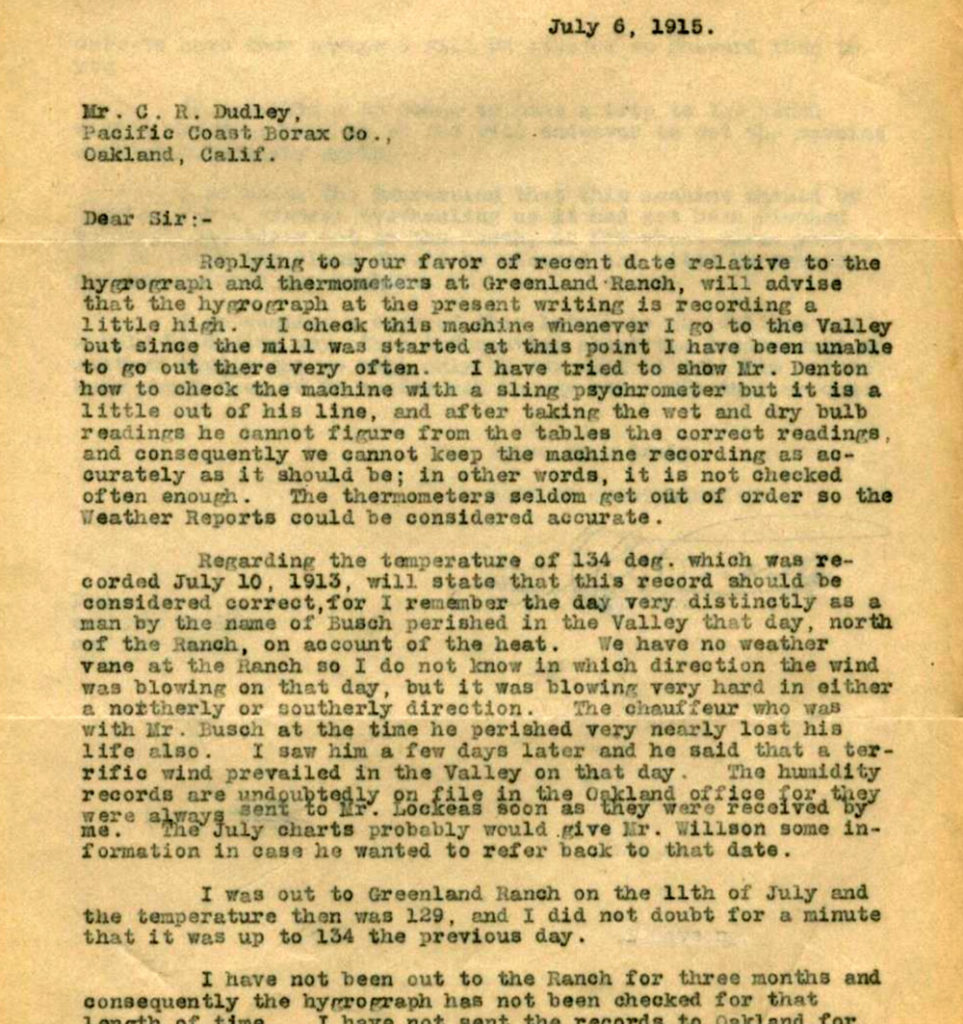

In 1915, Greenland Ranch superintendant Fred Corkill corresponded with the U.S. Weather Bureau in San Francisco regarding the weather, the weather station, the hygrograph in the instrument shelter, and the observer Oscar Denton (see letter from Corkill below). Corkill mentions that Denton was not able to interpret the humidity tables (the wet and dry bulb readings to get the relative humidity value, presumably) in order to calibrate the hygrograph.

This link goes to a newspaper note on Mr. Busch’s death in Death Valley, and more details are here. The second link states that the tragedy was on a Tuesday, which was July 8, 1913.

And what the heck, let’s just cut and paste that info here:

———————————

Las Vegas Age, December 18, 2003, NYE County, Nevada

Copyright © 2003 Gerry Perry <MissGerry@cox.net>

This copy contributed for use in the USGenWeb Archives.

************************************************************************

USGENWEB ARCHIVES NOTICE: These electronic pages may NOT be reproduced in

any format for profit or presentation by any other organization or persons.

Persons or organizations desiring to use this material, must obtain the

written consent of the contributor, or the legal representative of the

submitter, and contact the listed USGenWeb archivist with proof of this

consent. The submitter has given permission to the USGenWeb Archives to

store the file permanently for free access.

http://www.usgwarchives.net

************************************************************************

LAS VEGAS AGE

7/12/1913

BUSCH DEAD IN DEATH VALLEY

WELL KNOWN RHYOLITE MAN MEETS DEATH IN THE DESERT'S AWFUL SOLITUDES.

P. A. BUSCH, a member of the firm of BUSCH Brothers, located for the

past eight years at Rhyolite, met an awful death from thirst and heat in

Death Valley Tuesday last.

Having purchased a new automobile in Los Angeles, BUSCH attempted to

drive the machine from there to Rhyolite, accompanied by a young man

aged about 21, whose name is said to WHITE. After passing the Keane

Wonder mine on the border of Death Valley they were warned by a sheep

herder not to attempt the crossing on account of the intense heat. Not

deterred, BUSCH and WHITE went on. The sheep man, thereupon telephoned

to Rhyolite, advising that if the two did not make their appearance by

evening a relief expedition should be sent out.

When the travellers failed to appear, autos were started from

Rhyolite and the dead body of BUSCH discovered in the road within a mile

of the mine. Nothing was then known of WHITE. After bringing the body

of BUSCH to Rhyolite the searchers returned to seek further. They found

the young man, WHITE, at the automobile. He said that the machine had

stuck in the sand and that he and BUSCH were unable to extracate it.

The water in the canteen becoming low, BUSCH instructed him to go back

to Stove Pipe Springs to fill it. This he did, leaving BUSCH at the

machine. When the searchers found the body of BUSCH, WHITE was still

absent on his hunt for water, but succeeded in making his way back to

the machine with a small supply. It is supposed that BUSCH tried to

walk back to the mine, but fell, overcome with the heat and thirst

before he could make it.

The body passed through Vegas last night, being shipped to Colorado

for interment, accompanied by Frank BUSCH. A number of local Elks met

the funeral party at the depot and assisted in the transfer from the

L.V. & T. train to the Salt Lake Route.

--------------------------

The information above might be important because it was thought (well, at least I thought), that Corkill was specifically referring to July 10 when speaking of the death of Mr. Busch, and that Corkill was specifically stating that there was a “terrific wind” on the day of the 134F report (July 10, 1913). But that would not be the case if the death of Mr. Busch and the terrific wind were both on July 8th. So Corkill might be off a day or two. His letter was written two years after these events.

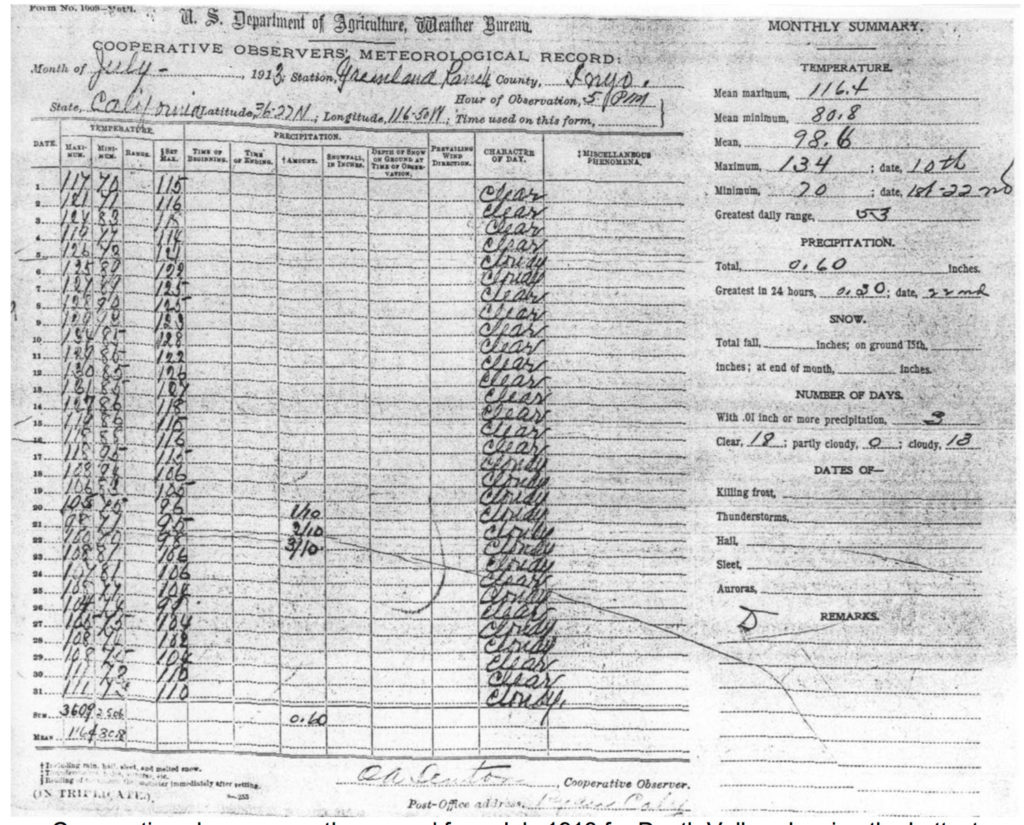

Below is the form for July, 1913, with Denton’s signature and temperature entries. Denton’s number-writing style was quite distinctive, and sometimes it is difficult to distinguish a “4” from a “9”:

Denton is mentioned frequently in articles and books on Death Valley and its record 134F temperature. Denton’s “Turkish towel” quote is a favorite. Sean Potter shares the quote in this 2010 article on the temperature record in Weatherwise Magazine.

A bit of research was done through ancestry.com and other online sources to learn more about Oscar Alan Denton. Let’s set up a timeline for Oscar:

——————————–

beginning of timeline for Oscar Alan Denton (1867-1944)

Disclaimer and caution: It is my belief that all of the information below pertains to Oscar A. Denton, the weather observer at Greenland Ranch from 1912 to 1920.

1867 born on May 18, 1867 (per California death index) Oscar was the third of eight children to Colonel William Denton and Elena Cano de las Ruiz

1868 baptized on January 4, 1868 in Baja California (per baptism record, info below)

| Name: | Oscar Allen Danton |

|---|---|

| Gender: | Hombre (Male) |

| Baptism Age: | 0 |

| Birth Date: | may. 1867 |

| Baptism Date: | 4 ene. 1868 (4 Jan 1868) |

| Baptism Place: | San Antonio de Padua, San Antonio, Baja California, México |

| Father: | Guillermo Danton |

| Mother: | Cano De las Ruiz |

Note that the spelling of “Denton” was a little different on the baptism document. Also, there are three variations in the spelling of Oscar’s middle name in the records: Alan, Allan, and Allen.

1874 Denton family moved to San Diego. The children attended school in San Diego (per Denton Family Papers)

1880 U.S. Census Information

Denton lived in San Diego with his family, including seven brothers and sisters.

| Name: | Oscar Denton | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age: | 13 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Birth Date: | Abt 1867 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Birthplace: | Mexico | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Home in 1880: | San Diego, San Diego, California, USA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Street: | Fifth | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| House Number: | 78 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dwelling Number: | 210 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Race: | White | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gender: | Male | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relation to Head of House: | Son | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Marital Status: | Single | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father’s Birthplace: | England | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother’s name: | Ellen Denton | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother’s Birthplace: | Mexico | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Attended School: | Yes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Neighbors: | View others on page | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Household Members: |

|

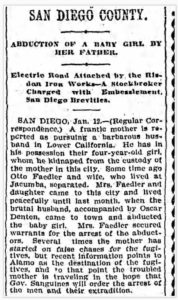

1897 According to this Los Angeles Times article of January 13, 1897 (below), Denton helped an acquaintance abduct the daughter of the acquaintance from her mother.

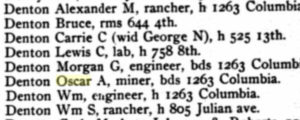

1904 Denton, age 37, lived in San Diego with other family members, according to the city directory. He is also listed in the San Diego directory for 1907, at 1812 Columbia.

| Name: | Oscar A Denton |

|---|---|

| Residence Year: | 1904 |

| Street address: | 1263 Columbia |

| Residence Place: | San Diego, California, USA |

| Occupation: | Miner |

| Publication Title: | San Diego, California, City Directory, 1904 |

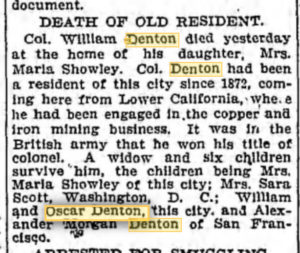

1907 Oscar’s father passes away in April. The notice below appeared beneath a San Diego header in the Los Angeles Times.

1907 Oscar Denton was occupying and “administering” his family’s large ranch at Jacume, which is in Mexico and along the U.S. border about 80 miles east of San Diego. This is according to an online historical account of the Denton family. More on this after the timeline below.

1910 sailed to San Diego from Rosalia Bay in Lower California on December 29, according to the manifest of alien passengers

| Name: | Oscar A Denton |

|---|---|

| Gender: | Male |

| Birth Date: | abt 1870 |

| Age: | 40 |

| Arrival Date: | 29 Dec 1910 |

| Port of Arrival: | San Diego, California |

| Ship Name: | Bernardo Reyes |

The manifests shows Denton’s occupation as “miner,” nationality as Mexican, last permanent residence as San Diego, and “Jacumba Ranch” as the place or address of a relative or friend in country from whence he came.

1911 sailed to San Diego from Ensenada, Mexico, on July 25, according to the manifest of alien passengers

| Name: | Oscar Denton |

|---|---|

| Gender: | Male |

| Birth Date: | abt 1869 |

| Age: | 42 |

| Arrival Date: | 25 Jul 1911 |

| Port of Arrival: | San Diego, California |

| Ship Name: | San Diego |

The manifest shows Denton’s occupation as “rancher,” his last permanent residence as “San Diego,” and his final destination as “San Diego.”

1912 Denton begins working for the Pacific Coast Borax Company as foreman of Greenland Ranch in Death Valley (per the cooperative weather station forms signed by him beginning in September, 1912). He turned 45 years old in May of 1912.

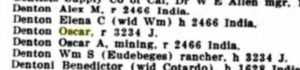

1919 Though he was working at Greenland Ranch, presumably, in 1919, Oscar Denton appears on city directory list of residents in San Diego. His name also appears in a list dated 1921.

| Name: | Oscar A Denton |

|---|---|

| Residence Year: | 1919 |

| Street address: | 2466 India |

| Residence Place: | San Diego, California, USA |

| Occupation: | Mining |

| Publication Title: | San Diego, California, City Directory, 1919 |

1920 U.S. Census Information

Though Denton lived and worked primarily at Greenland Ranch in Death Valley in early 1920, the census shows his home as Ryan, which was the nearest place with a post office at the time. (Denton worked for the Pacific Coast Borax Company, which had mining operations at Ryan, a relatively short drive from Furnace Creek.) He immigrated into the United States in 1876, when he was about 9 years old, according to this document.

| Name: | Oscar A Denton | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age: | 53 | ||||

| Birth Year: | abt 1867 | ||||

| Birthplace: | Mexico | ||||

| Home in 1920: | Ryan, Inyo, California | ||||

| House Number: | Farm | ||||

| Residence Date: | 1920 | ||||

| Race: | White | ||||

| Gender: | Male | ||||

| Immigration Year: | 1876 | ||||

| Relation to Head of House: | Head | ||||

| Marital Status: | Single | ||||

| Father’s Birthplace: | England | ||||

| Mother’s Birthplace: | Mexico | ||||

| Native Tongue: | English | ||||

| Able to Speak English: | Yes | ||||

| Occupation: | Manager | ||||

| Industry: | General Farm | ||||

| Employment Field: | Wage or Salary | ||||

| Home Owned or Rented: | Rent | ||||

| Naturalization Status: | Papers Submitted | ||||

| Able to Read: | Yes | ||||

| Able to Write: | Yes | ||||

| Neighbors: | View others on page | ||||

| Household Members: |

|

1921 Married Berdie Jernigan Slaton in Indiana on May 30. Denton had just turned 54 years of age, and not 50 as indicated below. The birth date given is likely incorrect.

| Name: | Oscar Alan Denton |

|---|---|

| Gender: | Male |

| Birth Date: | 1871 |

| Marriage Date: | 30 May 1921 |

| Marriage Place: | Evansville, Vanderburgh, Indiana |

| Marriage Age: | 50 |

| Father: | William Denton |

| Mother: | Elena Cano de los Rios |

| Spouse: | Berdie Jernigan Slaton |

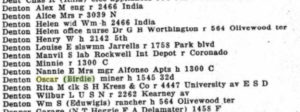

1923 Denton appears on a list of residents in San Diego, per the San Diego City Directory. His wife of two years is also noted.

| Name: | Oscar Denton |

|---|---|

| Gender: | Male |

| Residence Year: | 1923 |

| Street address: | 1545 32d |

| Residence Place: | San Diego, California, USA |

| Occupation: | Miner |

| Spouse: | Birdie Denton |

| Publication Title: | San Diego, California, City Directory, 1923 |

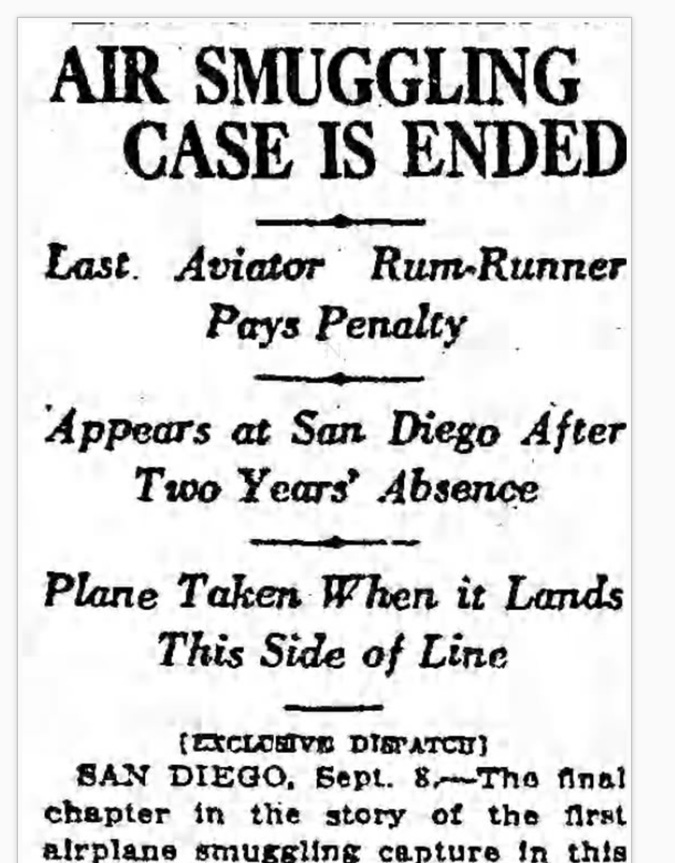

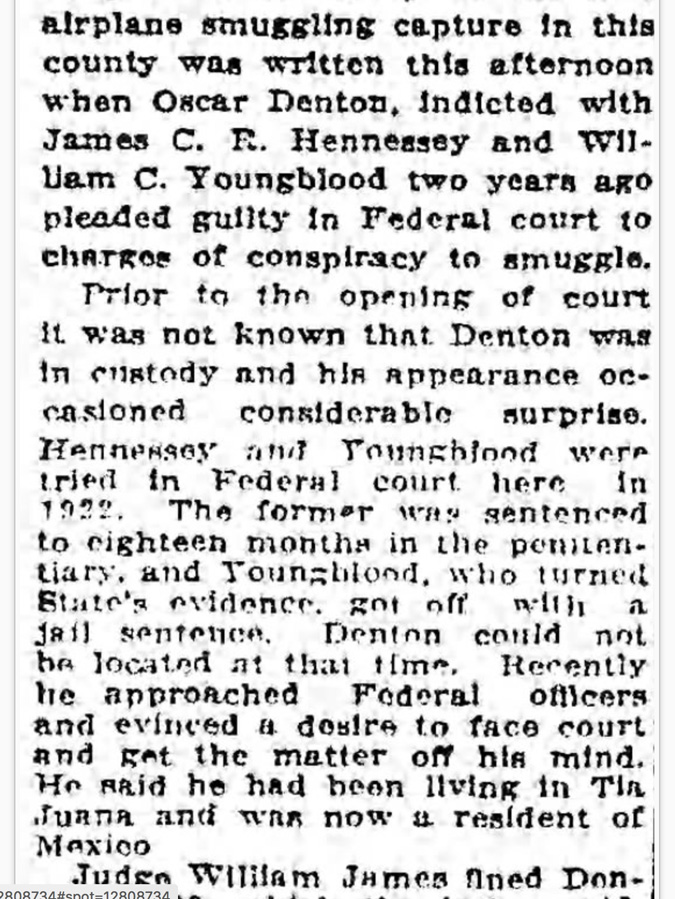

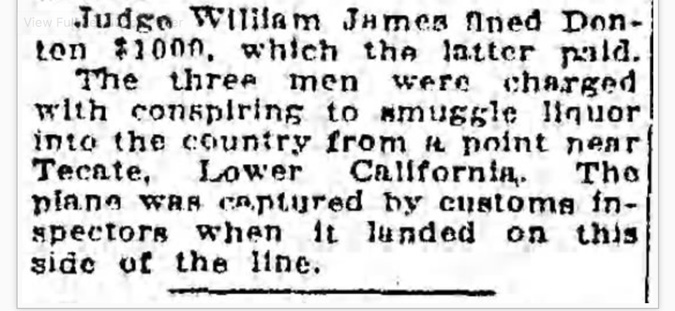

1924 Denton turns himself in to authorities in San Diego to face liquor smuggling charges from two years prior. He was living in Tijuana, Mexico, during this timeframe, according to this article of September 9, 1924, in the Los Angeles Times.

1928 Denton and wife Berdie are listed in the San Diego city directory. Oscar worked as a laborer for the Fenton Parker Material Corporation.

| Name: | Oscar A Denton |

|---|---|

| Gender: | Male |

| Residence Year: | 1928 |

| Street address: | 1545 32d |

| Residence Place: | San Diego, California, USA |

| Occupation: | Laborer |

| Spouse: | Berdie J Denton |

| Publication Title: | San Diego, California, City Directory, 1928 |

1930 U.S. Census Information

According to the 1930 census, Denton was not a U.S. citizen, and he immigrated back into the U.S. in 1918 (which is odd as he was the weather observer in Death Valley from 1912 to 1920).

| Name: | Oscar A Denton | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth Year: | abt 1867 | ||||||

| Gender: | Male | ||||||

| Race: | White | ||||||

| Birthplace: | Mexico | ||||||

| Marital Status: | Married | ||||||

| Relation to Head of House: | Head | ||||||

| Home in 1930: | Santa Rita, Merced, California | ||||||

| Map of Home: | View Map | ||||||

| Dwelling Number: | 211 | ||||||

| Family Number: | 218 | ||||||

| Home Owned or Rented: | Owned | ||||||

| Radio Set: | Yes | ||||||

| Lives on Farm: | Yes | ||||||

| Age at First Marriage: | 53 | ||||||

| Attended School: | No | ||||||

| Able to Read and Write: | Yes | ||||||

| Father’s Birthplace: | England | ||||||

| Mother’s Birthplace: | Mexico | ||||||

| Language Spoken: | Spanish | ||||||

| Immigration Year: | 1918 | ||||||

| Naturalization: | Alien | ||||||

| Able to Speak English: | Yes | ||||||

| Occupation: | Farmer | ||||||

| Industry: | General Farming | ||||||

| Class of Worker: | Working on own account | ||||||

| Employment: | Yes | ||||||

| Household Members: |

|

1930 Oscar’s mother dies on September 30

1940 U.S. Census Information

| Name: | Oscar A Denton | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent: | Yes | ||||||

| Age: | 73 | ||||||

| Estimated birth year: | abt 1867 | ||||||

| Gender: | Male | ||||||

| Race: | White | ||||||

| Birthplace: | Mexico | ||||||

| Marital Status: | Married | ||||||

| Relation to Head of House: | Head | ||||||

| Home in 1940: | Merced, California | ||||||

| Map of Home in 1940: | View Map | ||||||

| Farm: | Yes | ||||||

| Inferred Residence in 1935: | Same House, Merced, California | ||||||

| Residence in 1935: | Same House | ||||||

| Citizenship: | Alien | ||||||

| Sheet Number: | 6A | ||||||

| Number of Household in Order of Visitation: | 108 | ||||||

| Occupation: | Farmer | ||||||

| House Owned or Rented: | Owned | ||||||

| Value of Home or Monthly Rental if Rented: | 1500 | ||||||

| Attended School or College: | No | ||||||

| Highest Grade Completed: | High School, 4th year | ||||||

| Hours Worked Week Prior to Census: | 48 | ||||||

| Class of Worker: | Working on own account | ||||||

| Weeks Worked in 1939: | 50 | ||||||

| Income: | 0 | ||||||

| Income Other Sources: | No | ||||||

| Neighbors: | View others on page | ||||||

| Household Members: |

|

1940 Oscar’s wife dies

1944 Oscar Denton dies on November 30, according to the California Death Index:

| Name: | Oscar Allen Denton |

|---|---|

| Gender: | Male |

| Birth Date: | 18 May 1867 |

| Birth Place: | Mexico |

| Death Date: | 30 Nov 1944 |

| Death Place: | Merced |

end of timeline

——————————————-

Oscar Denton came from a wealthy and influential family that lived in Mexico and San Diego. In fact, there are libraries in the San Diego area with archives of the Denton family and its history. Here is a brief summary for the “Denton Ranch Collection” at the Mandeville Special Collections Library at La Jolla:

Historical Background

Col. William Denton (1828-1907), an English civil engineer, came to California during the Gold Rush, worked for the United States geodetic survey and later pursued an interest in mining exploration and speculation in Mexico. In 1860, he married Elena Cano de los Rios of Mulege, Baja California and eventually moved his family to San Diego in 1874. Denton became a naturalized Mexican citizen in 1896.

In 1885, Col. Denton purchased two thousand five hundred hectars (6,175 acres) of land in Mexico known as “Jacumbo” from Senora Higinia Tortoledo for five hundred pesos. Rancho Jacume, as it was known locally, was located on the frontier of the Northern District of Lower California, Mexico on the international border. Col. Denton maintained his residence in San Diego, where his children were educated, and used Rancho Jacume for cattle grazing.

At the time of his death in 1907, Col. Denton’s estate was largely comprised of properties in Baja California, Mexico. He owned an undivided interest in Rancho Algodones, located on the Colorado River in Baja California; Rancho Jacume; and half interest in the mines known as Toronjil, Angel de la Guardia, Nueva Esperanza, La Vaca, Tarantula, the Chubasco group, the Sireno group, Santa Rosa, Alice, Josephina, Ajax and Vulcan. Denton worked in a mining partnership with H.A. Howard of San Diego, who provided capital for survey expenses, title acquisition, and taxes.

Upon Col. Denton’s death, title to the Denton Ranch was divided between his wife, who received a one half interest, and his children, William Smith Denton, Oscar Alan Denton, Sara Brent Denton Scott, Alexander Marion Denton, Maria S. Denton Showley and Morgan Gascoigne Denton. Elena Denton willed her property equally to Sara Denton Scott, Maria Soledad Denton Showley, Morgan Gascoine Denton, and Samuel John Murvin Showley. Oscar Alan Denton occupied the Denton Ranch and administered the property.

In 1939, the Denton Ranch was expropriated by the Mexican government and ownership transferred to a newly form ejido, or agricultural collective. Over the next seven years, Maria Denton Showley and her brother, Morgan Denton, pursued a suit with the American Mexican Claims Commission for compensation and on June 28, 1946 a settlement was reached.

And below is a similar summary, from the Denton Family Papers at the San Diego History Center:

BIOGRAPHICAL / HISTORICAL NOTES

Colonel William Denton (July 27, 1828-April 14, 1907) was born in Harrowby, England, to William Smith Denton and Sarah Nixon. He was the fourth of seventeen children. Denton came to the United States during the Gold Rush and worked as a civil engineer for the United States geodetic survey. Between 1858 and 1860, Denton participated in a surveying expedition of the Sea of Cortes and coastal Sonora region, accompanied by Federico Fitch, son of a prominent San Diego businessman. It is very likely that he met his future wife during this expedition since their ship stopped at her hometown of Mulege, Mexico. In 1860, he was married to Elena Cano de los Rios aboard the English battleship “The Cleo” at La Paz, Mexico. Elena Cano de los Rios Denton (May 8, 1845-September 23, 1930) was born in Mulege, Baja California, to Mariano Cano de los Rios and Petra Ruiz. Together, William and Elena had eight children: Eleana, William Smith, Oscar Allan, Sarah Brent, Paul Isham, Alexander Marion, Maria Soldad, and Morgan Gascoigne.

In 1874, the Denton family moved to San Diego, where they remained for many years. Denton was employed by the International Colonization Company as a land surveyor in the Baja California region between 1884 and 1886, when he appears to have had a falling out with the powerful North American land syndicate. William Denton became a naturalized Mexican citizen in 1894 and was a prominent landowner in Baja California. Although at the time of his death, his American estate totaled only $1000, he owned several mines and ranches in Northern Baja California. These included: the Blanco Bay and Trinidad iron mine groups; Los Algodones Rancho, situated near the Colorado River; Rancho Jacume, situated on the U.S.-Mexican border; one-half interest in Toronjil, Angel de la Guarda, Nueva Esperanza, and La Vaca copper mines, situated on the Pacific coast; one-half interest in the Chubasco and Sireno gold mine groups; and one-half interest in the Vulcan iron mines, situated near the Pacific Coast.

Upon Col. Denton’s death, his estate was shared amongst his family: half going to his wife, and the other half split evenly among his remaining children. His son Alexander appears to have taken over much of the responsibility for maintaining the family’s properties after Denton’s death. Alexander Denton carried on his father’s work as a land surveyor, drawing up several maps of the Baja California region that encompassed the Denton property in Mexico.

William Denton’s daughter Maria Soldad was married to Sam Showley. The couple had two children: Samuel Denton Showley and Dan Showley. Dan Showley, who donated at least part of this collection, was a teacher of Spanish and History at Hoover High School.

Oscar’s father died in 1907, and he left his possessions to his family. Below is Colonel William Denton’s will:

Based on the timeline information, Oscar Denton grew up in the northern Baja California peninsula and later in San Diego, California, from ages 7 to 13 (if not later). He received a high school education, but he did not attend college. His family owned a large ranch property in Mexico by the name of Rancho Jacume by the time he finished high school, according to a footnote (below) by Benjamin Johnson in Bridging National Borders in North America (Page 138).

Oscar’s father, William, was a successful surveyor and miner and rancher. Oscar presumably helped to run Rancho Jacume while in his 20s and 30s, circa 1887 to 1907. According to a couple of ship manifests in 1910 and 1911, Oscar gives “miner” on one and “rancher” on another as his occupation. This work and experience no doubt helped Oscar to get the position as foreman and caretaker at Greenland Ranch in Death Valley in 1912, five years after the death of his father. Oscar was reportedly a loner, and his Greenland Ranch job certainly was a lonely one. Though the Greenland Ranch position as foreman might have been the perfect fit for him, why would Denton abandon what was probably a fairly comfortable living for the harsh conditions of Death Valley? This question seems to be answered by Dane Coolidge in “Death Valley Prospectors.” Coolidge says that Denton was looking to escape detection by individuals who wished to do him harm, following an unpleasant encounter at his family’s ranch in Mexico.

Rancho Jacume is at an elevation of about 2800 feet, which is about the same as Campo, California, to its west. The average maximum temperature for July at Campo is about 94F. Farther inland, Rancho Jacume might be slightly warmer than Campo in summer. Oscar was no doubt somewhat familiar with desert conditions and desert heat prior to heading to Death Valley, but the family ranch was about 20 degrees cooler on average than Death Valley in summer.

Why did Oscar decide to head to the Mojave Desert and Death Valley? Did he learn of the need for a foreman at Greenland Ranch before heading that way? Did he head north into California and Nevada to try his luck in the mines around Rhyolite, which started to flourish around 1906? Did his well-known father know “Borax” Smith and/or Fred Corkill, the managers of the borax works in Death Valley?

Though Denton did not receive any formal schooling after high school, according to census records, he came from a well-to-do family and likely had some familiarity with mathematics and some sciences. It is a bit strange, perhaps, that Denton was found to be unable to work out the humidity values, as Corkill stated in the letter to the USWB. The Greenland Ranch climate record while Denton was the observer is plagued by errors, contains a plethora of obviously contrived data, and suggests that the observer had a tendency to stray from standard operating/observing procedures. Why was Denton unable to fulfill his weather-observing duties properly? Why did he feel compelled to do things his way, and not the proper way? Or, was he just inadequately trained as observer, and unsure of what to do in certain circumstances?

Summary of Part 6

This rather lengthy entry and all of this research is intended to provide the interested reader with background on

–life in Death Valley during the borax period,

–the history of the borax company’s “Greenland Ranch” at Furnace Creek,

–the history of the weather station at Greenland Ranch

–the weather observer who made the observation of 134F in 1913, Oscar Denton.