UNRAVELING DEATH VALLEY’S RECORD HIGH TEMPERATURE (easy as 1-3-4)

by William T. Reid

Update, November, 2020 — This research study is definitely a “work-in-progress.” The ultimate goal is to shed light on the improbability of the ultra-high maximum temperatures at Greenland Ranch in July, 1913, including the U.S. and world record of 134F set on July 10, 1913. Along the way, we will learn about how temperatures behave during desert heat waves, and we will see that the world’s record high temperature is not authentic.

Amazingly…well, somewhat amazingly, a temperature of 130F was officially recorded at Death Valley on August 16, 2020! See the links below for more on that event. It was not particularly amazing that the current Death Valley station finally attained a reliable maximum temperature of 130F. But it WAS amazing that such a record occurred in mid-August, and not during July. Monthly maximums at Death Valley in 2020 included

128F in July (one degree short of the all-time reliable record of 129F),

130F in August (a new all-time reliable record and 3 degrees higher than the previous record maximum for August),

125F in September (two degrees higher than the previous record maximum for September)

and 112F in October (one short of the record maximum for October).

You are on PART ONE of this research study, and links to the other parts are below.

A new, slimmed-down write-up which sums up the most important research which discredits the 134F maximum from 1913 is here:

You are on PART ONE of this research study. Links to the other parts in Stormbruiser are below.

Part Two is here (The early Greenland Ranch record is scrutinized)

—

Part Three is here (Comparing hot maximums)

—

Part Four (Historic Heat Waves)

Part 4A (1931 to 1960 Heat Events)

Part 4B (1961 to 2017 Heat Events)

Part 4C (1911 to 1930 Heat Events)

—

Part Five (Supplemental Data Tables)

—

Part Six (Oscar Denton and Greenland Ranch)

Part 7 Miscellaneous Notes and Correspondence (from NPS)

Part Eight Original Charts

Other posts by me regarding Death Valley high temperatures:

Link to Record 130F Temperature at DV in August, 2020

August 17, 2020 Drive to DV with Weather Station Pictures

Decline of the Quality of the Exposure of the Death Valley Weather Station

Link to October 2016 WeatherUnderground article (collaboration with WU blogger Christopher Burt)

Link to detailed temperature study on a hot summer afternoon in Furnace Creek

————————————–

Outside links:

Climate of Death Valley (by NWS Las Vegas)

History of Weather Observations (at Death Valley) by NWS Las Vegas/Chris Stachelski

NWS Las Vegas Research/Chris Stachelski “Twelve Significant Weather Events” (at Death Valley)

Temperature Record (by NWS Las Vegas/Chris Stachelski)

—

PART ONE —- BACKGROUND

This research was first published on Stormbruiser.com by me (William T. Reid) during the summer of 2013. I have done a bit of editing and updating in November, 2020.

“Be skeptical.”

That was the advice provided to me and to my fellow students in a Climatology class back in 1978 at California State University, Northridge. The instructor was Dr. Arnold Court. He showed the class reams and reams of climate data: hourly data, daily data, annual data, extreme data. The weather data are lined up in neat rows and columns and appear so perfect and precise and beyond repute. But how did these numbers come to be? Are the data to be trusted? Were the weather instruments working properly at the time? Were they regularly calibrated and maintained? Were they sited and exposed properly? Were the observers properly trained and adequately conscientious, committed, and capable to ensure quality weather records? Exactly how did the observation get from Station X and into this book, or file?

In that same class that semester, Dr. Court commented briefly on the U.S. maximum temperature record of 134F, set on July 10, 1913, in Death Valley, California. He said that the figure was not trustworthy. Dr. Court believed that there may have been a problem with the instrumentation, which resulted in inflated high temperature figures during that month. I was astounded! This was blasphemy! “134 degrees Fahrenheit” was like the Holy Grail of weather and climate figures! It was as if he had said that Babe Ruth had homered only 658 times, and not 714. How could such an important, long-term record NOT be valid?

Fast forward to the year 2013, and even to the year 2020! It has been 107 years since the record 134F temperature report. I am convinced that the report is bogus. More than 100 years of temperature records from Death Valley do not support the 134F maximum and the other maximums from 127F to 131F from Greenland Ranch in Furnace Creek, Death Valley, during July 1913. More importantly, the record July 1913 Death Valley maximums are not supported by the maximum temperatures at stations closest to Death Valley during the same time frame. My mission here is to throw as much light as possible onto Death Valley’s 134F record temperature. I suspect that, if an official investigation into the record were undertaken, that the value would be found suspect. It would be found to be VERY SUSPECT. In order to discredit the 134F maximum temperature, a familiarity with the weather and climate of Death Valley and the surrounding desert areas is essential. This study aims to help the reader understand why the record maximum temperature for the United States for the previous 100-plus years is not valid. Remember —- be skeptical!

We’ll look closely at the 134F record in the pages that follow, but first a relatively brief explanation of why the record is suspect would be helpful. Official weather stations in Furnace Creek and vicinity have been in operation since June of 1911. All of the annual maximum temperatures for 110 summers (through 2020) here have ranged from 119F to 130F, except for the 134F for 1913. Incredibly, eight consecutive days in July, 1913 at Greenland Ranch had maximums of 127, 128, 129, 134, 129, 130, 131 and 127F. Why was only 1913 able to reach 130F and higher? Was there a super heat wave in the region in July 1913? Maximum temperatures at the closest surrounding stations during this 8-day period were NOT especially high. Maximums were running generally 3-to-8 degrees above average at the closest surrounding stations, compared to 12-to-18 degrees above average at Greenland Ranch. (The average daily maximum temperature for July at Greenland Ranch was about 116F). It will be shown in this study that the conditions that result in the hottest weather in Death Valley and the Mojave Desert in summer are not localized! If one station is well above average on maximum temperature, then other surrounding areas are also well above average. Maximum temperatures in the region in summer are very predictable, as the upper-level high pressure systems that are responsible are quite homogeneous and smother huge portions of the country. Daily maximum temperatures in summer in Death Valley and the Mojave Desert are in large part a function of the temperature at low-to-mid levels of the troposphere, at altitudes from around 5000 to 15,000 feet. Mixing between the surface and the low-to-mid levels of the troposphere is excellent on sunny summer days in the region, and air temperature decreases with elevation at rates approximating the dry adiabatic lapse rate (about 5.4 degrees F per 1000 feet). When Death Valley is hot in summer, then surrounding areas routinely reflect and support the Death Valley high temperature reports. This was not the case during the first two weeks of July, 1913. (There are occasional exceptions, of course, especially when moisture and clouds and precipitation move into parts of the region and cause cooling. However, the hottest temperatures year-to-year are almost always associated with clear skies, low humidities, and excellent mixing region-wide.)

Perhaps the 134F temperature was a one-day fluke, or perhaps something extraordinary and local occurred. If so, why has it not been documented since? Why have we not observed other “fluky,” yet “authentic,” exceptionally hot weather spikes at Death Valley or other desert stations which might serve to adequately explain the July 1913 record? Consider that there were four other days during that week in July, 1913, with maximum temperatures from 129F to 131F, and three others from 127F to 128F. Did fluky weather conditions result in these ultra-high maximums each day for an entire week in July 1913 in Death Valley? It would be difficult to believe that! Outside of 1913, the Greenland Ranch maximum thermometer never indicated a temperature greater than 127F! Greenland Ranch records spanned 50 years, from 1911 to 1960.

Why was Death Valley reporting such high maximum temperatures compared to normal in July, 1913, while surrounding stations did not? If the lower and mid-levels of the atmosphere are well-mixed, these types of anomalies are physically not possible. If the low-to-mid levels of the troposphere can support maximums that are only 3-to-8 degrees above average for July region-wide, then it is not warm enough to support authentic maximum temperatures that are 12-to-18 degrees above normal, for an entire week, at only one particular station. Given the maximum temperature reports from the closest surrounding desert stations, the temperature of the air inside of the thermometer shelter at Greenland Ranch weather station in Furnace Creek could not have been as high as 130F during July, 1913. The regional reports suggest that Greenland Ranch was likely no warmer than 125F or 126F during July, 1913.

How can the anomalously hot maximum temperature reports from Greenland Ranch in July 1913 be explained? They seem to be about 8-to-10 degrees too high, given the maximum-temperature record at surrounding stations such as Independence, Lone Pine, Goldfield, Tonopah, Oasis Ranch, Las Vegas and Barstow. Either the instruments and/or equipment were not working as intended, or the observer erred (perhaps by inappropriately “fudging” the data), or both. If the reports are authentic, then something that I, and science, cannot adequately explain occurred on a number of afternoons at or around the station. If the reports are not authentic, then it is time to reconsider the all-time record maximum temperature for the United States…and the world.

My research leads me to believe that the suspect maximums in July 1913 were artificially inflated by the observer at the time, Oscar Denton. Denton may have moved the official instrumentation, or may have been relying on other thermometers at the ranch, instead of following the procedures which he should have been following. More details on this supposition of mine are discussed below.

This study is divided into several parts. Part One is concerned with the meteorology of the region in summer, the history of weather stations in Death Valley, previous studies regarding Death Valley climate and its record hot week in July 1913. There are numerous links and reproductions to allow the reader ample opportunities to become very familiar with Death Valley temperatures and climate. Part Two is concerned primarily with the quality of the climate record from Greenland Ranch for its first ten years of operation. Part Three will compare summer maximum temperatures in the Death Valley region. (Near the top of this page are the links to these and other “parts” of the study.) By demonstrating just how anomalously hot the July 1913 reports are, compared to long-term records and surrounding station data, it should be clear that Death Valley’s 134F report and its other extremely hot maximums from July 1913 are not to be trusted.

Another note: I would hope that you, the reader, are curious as to the credentials of this researcher. At the bottom of this page is a blurb about myself and my weather and climate background.

SUMMERTIME HEAT IN DEATH VALLEY AND THE MOJAVE DESERT

The record 130F-plus temperature reports from Death Valley in 1913, as we’ll see, are not supported by the climatology. To better understand the high-temperature climatology of the region, it is imperative to understand the meteorology which causes the hottest days.

The Death Valley and Mojave Desert regions (roughly from the Antelope Valley and Owens Valley on the west to U.S. 6 on the north to U.S. 95 on the east to I-40 on the south) are hottest during the summer, when the sun is highest midday and when daylight hours are longest. Average annual rainfall amounts in the lowest basins are only two to four inches. Ground surfaces and soils are bone dry by early-to-mid summer, and any vegetation is sparse and adapted to transpire at minimal levels. Daytime insolation energy goes almost exclusively towards heating the ground. The heated rocks, alluvium, and desert surfaces in turn warm the air just above the surface and the material below the surface. Unlike non-desert areas, little to no daytime insolation is “wasted” or “spent” on evaporation and transpiration. The dry desert surfaces are slow to cool at night. In summer, Death Valley is akin to a huge urban heat island, as the mostly barren surface radiates effectively back into the lower atmosphere. Only the isolated grassy areas around springs and oases can cool down much on summer nights, if the wind is not strong.

By late spring and into the summer, mid-tropospheric troughs of low pressure into Southern California and vicinity are weaker and weaker and less numerous. Winds at mid and high-levels of the troposphere weaken, and the intense daytime surface heating over the desert areas contributes to warming of the lower and mid-levels of the troposphere. As the troposphere above the desert regions warms, air densities decrease, 500-millibar heights increase, and a large mid-to-upper-level anticyclone develops. Subsidence associated with these upper-level high pressure systems promotes clear skies, and warming and drying at low and mid-levels (this is roughly below the 500mb level, or below about 18,000 feet above sea level). Summertime upper-level high-pressure systems are common above mid-latitude desert regions, as surface conditions help to support the maintenance of the upper-level system, and the upper-level system helps to maintain dry and hot weather conditions at the surface. These mid/upper-level high-pressure areas typically sprawl over great expanses, and, when situated somewhere over the Desert Southwest, generally bring near-to-above-normal maximum temperatures to all or most desert stations below. (The usual caveat applies: if moisture levels are high enough to allow significant convection, cloudiness, and/or rain-cooled air, which is not unusual around the fringes of the upper high, then maximum temperatures may be tempered.)

The relatively weak winds and subsidence associated with upper-level highs above the Death Valley and Mojave Desert regions are ideal for “building” heat waves. Cooler air masses at mid-levels from adjacent regions find it difficult to penetrate these upper highs. At the surface, a “thermal low” low-pressure area develops beneath the upper high. The thermal low can draw cooler air from distant sources towards it, but the region protects itself well from cool intrusions. Cool marine air along the beaches of the California coast occasionally seeps into the western deserts in summer. But, when an upper-level high/anticyclone is over the region, the marine layer is shallow and the top of the inversion is well below pass levels into the deserts. The Coastal Ranges, Sierra Nevada, Tehachapi and Transverse Ranges, among other mountain ranges, effectively block cooler low-level air masses west of the Mojave Desert and Death Valley. Air drawn in from the Great Basin (to the north and northeast) is warm and dry due to the upper high and desert terrain, and warms and dries further as it slips downslope into even lower basins. Air pulled northward or northwestward from the Colorado Desert region of Arizona, southern California and Sonora, Mexico is typically hot and dry. However, the air masses from the south tend to moisten up into mid-and late summer. Muggy low-level air tends to be cooler, more stable, and resists “mixing out” compared to dry low-level air. Humid “gulf surges” from the Sea of Cortez often affect the lower Colorado River Valley, from Yuma to Needles, but these moist low-level air masses are usually not deep enough to progress much farther northwest past Interstate 15 from Victorville to Las Vegas.

The lower and middle levels of the troposphere above the Mojave Desert and Death Valley regions are VERY WELL MIXED in summer! This is key! This is the underlying reason why 134F was impossible on July 10, 1913 in Death Valley, given the surrounding station maximum temperatures. The high sun warms the desert surfaces during the day, and the air that is warmed along the surface mixes upward until it is at an equilibrium with the surrounding air. During the first few hours after sunrise, the ascent might only be ten feet, one hundred feet, one thousand feet. However, by early-to-mid afternoon, deep mixing is in progress, and dry convection stretches from the surface to thousands of feet above the surface. Dry air in the afternoon convection warms and cools at the dry adiabatic lapse rate as it descends and rises. Afternoon temperature soundings at Desert Rock and Las Vegas, NV, on the hottest summer days invariably show steep lapse rates from the surface to the 600-millibar level, approximately. A shallow near-surface layer (above a typically mostly-barren desert surface) with a super-adiabatic lapse rate is common, above which temperature decreases at or very near the dry adiabatic lapse rate of 5.4 degrees F/1000 feet. The troposphere can not support lapse rates steeper than the dry adiabatic lapse rate (above the shallow super-adiabatic layer). Air with a super-adiabatic lapse rate develops within a hundred meters or so of the surface during intense afternoon heating, but the atmosphere is continually hard at work to minimize, or mitigate, or eliminate, these excessively steep lapse rates. The atmosphere will not permit one particular desert locale to become significantly warmer than an adjacent location (at a similar elevation) thanks to persistent and efficient mixing in the lower troposphere.

During the deep and dry afternoon convection above a desert basin, such as Death Valley, the ambient air temperature (as measured in a thermometer shelter or by a sensor in the radiation shield, about five feet above the ground) is “governed” by the temperature aloft. Because the desert atmosphere is well mixed and because environmental lapse rates can not be steeper than the dry adiabatic lapse rate, afternoon high temperatures can only get as warm as the air aloft will allow. Keep in mind that we are assuming areas which are well-ventilated and well-exposed, above typical ground cover — areas in which weather stations should be sited! This allows maximum temperature forecasts on sunny and dry summer days in the Mojave Desert to be very predictable. Temperatures from about the 850-millibar level up to the 650-millibar level govern ambient surface air temperature during the afternoon in the desert basins. In other words, the temperature of the air aloft effectively limits the extent to which the ambient surface air can warm during daytime heating (or during any time of the day, for that matter). A study by Williams for the U.S. Army in 1967 examined the conditions favoring high surface temperatures at Yuma. He determined that the key to high ambient air temperatures at Yuma is “warm air between 5000 and 14,000 feet and a well-developed vertical exchange induced during the afternoon convection.” The study found that “there exists an upper limit to what the combination of radiation and ground surface temperature can do in developing high ambient air temperatures.”

Maximum temperatures correlate very closely to the temperature of the free air aloft (around 700 mb), with elevation as the primary factor explaining temperature difference from place to place, or station to station, beneath the upper high. (Again, an introduction of moisture, deep moist convection, widespread cloudiness, etc., can disrupt the strong correlation…but clouds and moisture are generally absent on the hottest summer days in the region.). Upper-level high pressure systems are associated with very weak temperature gradients between about 10,000 and 15,000 feet above sea level (between about 700 and 600 mb), so climate stations in any particular region in the desert are “working” off of the same airmass, generally speaking, on any particular summer afternoon during such conditions. Thus the difference in maximum temperature on a day-to-day basis between desert stations tends to be quite consistent beneath the upper-level highs in summer.

So, to summarize and reiterate and emphasize!

The ingredients which contribute to hot summer afternoons in the Mojave Desert and Death Valley regions are:

— a very dry and bare-to-sparsely-vegetated desert surface, high midday sun, a transparent atmosphere with clear to mostly clear skies

—excellent mixing both vertically and horizontally at low levels during the afternoon

—excellent mixing between the surface and low-to-mid levels of the troposphere, up to 650 mb or higher

—a relatively warm and homogenous air mass covering the region between about 850 and 600 mb

—distance and orographic protection from the cooling influences of the Pacific Ocean and other moisture sources

—and, of course, plenty of low-elevation areas. The lowest places are hottest because of compression and mixing.

Many published discussions which attempt to explain the very hot summer afternoon temperatures in Death Valley will point to its low elevation and then something to the effect that the “heat” in the basin is trapped somehow due to the adjacent high and steep mountainsides. The heated air in the basin bottom rises along the mountainsides and then comes back down and heats via subsidence (purportedly!). I don’t believe that I have come across any study which adequately explains the “trapped heat” explanation! I would not equivocally state that an explanation of this type has no merit meteorologically, but I do not find that it is a particularly good reason to explain Death Valley summertime heat. There are plenty of other desert basins near and not-so-near Death Valley that are rimmed by tall desert mountains. The meteorology is the same in these basins as it is in Death Valley. The reason why the bottom of Death Valley is hotter and drier than these other basins and valleys — Panamint, Saline, Owens, Eureka, etc. — is because it is at a lower elevation. The air that mixes to the bottom of Death Valley basin warms further (comparably) due to the increase in compression. The additional warming due to lower elevation results in lower relative humidities and an increasingly hostile environment for vegetation.

From a meteorological, geographical and geomorphological perspective, it would seem that Death Valley is just about in the perfect spot in order for it to be the “winner” for high temperature measurement, in North America at least. It is its low elevation and location geographically with respect to moisture sources which set it apart. The high and steep slopes on the sides of Death Valley may, or perhaps I should say “probably,” aid or enhance high temperatures (on the basin bottom) to some degree by promoting mixing to higher levels, i.e., to levels where the potential temperature is higher. The deeper the mixing on a summer afternoon, the higher the ambient surface air temperature will be. Presumably, a deep basin that is adjacent to plenty of high-elevation terrain will have an advantage in high summer temperatures versus a similar-elevation area or basin which is not so deep, and/or which is adjacent to lower-elevation terrain comparably.

A well-mixed atmosphere below 700 mb results in a strong correlation between maximum temperature and elevation in the region on typical sunny days in summer, and the following are also strongly correlated to elevation (for warm-season months) in the region:

—average daily maximum temperature

—average monthly maximum temperatures

—average annual maximum temperature

—all-time record maximum temperature.

See my Masters Thesis for a comparison between temperature and elevation in the region (beginning at page 233).

During a typical, dry, summertime warm period in the Death Valley and the Mojave Desert regions, area weather stations record daily maximum temperatures which are quite comparable to those at nearby stations with regard to departure from the normal daily maximum temperature for the month. If a station is, for example, five degrees warmer than normal for a particular day, then it is highly likely that nearby stations (which might be as much as 50 to 100 miles distant) will also have maximum temperatures that are approximately five degrees warmer than normal (i.e., within a couple of degrees of “five degrees warmer than normal”). On the warmest, dry, summer days, one will NOT find large ranges or spreads in “departures from normal” among stations in a particular region. If one station has a legitimate maximum which is close to an all-time high temperature, then other nearby stations will be relatively close to their all-time highs. If most stations are only a few degrees warmer than normal, then it would be very, very unusual, if not impossible, to have a station in their midst record a legitimate temperature near all-time record levels (and perhaps 10-to-15 degrees above normal).

On typically warm-to-hot and dry summer afternoons, the temperature from about 5000 to 14,000 feet effectively governs, controls, and limits the daily maximum temperatures for the region. If the airmass aloft is supporting maximum temperatures which are, for example, 2-to-6 degrees above normal, then it is not warm enough to support air temperatures some 10, 12, or 14 degrees above normal. If the airmass is warm enough to support near-record maximum temperatures that are 10-to-14 degrees above normal, then all desert stations under the influence of this airmass will have near-record maximums that are about 10-to-14 degrees above normal. You will not find region-wide, near-record maximum temperature reports AND a legitimate near-normal maximum temperature report in their midst. (Again, this is assuming typical, dry, summer conditions; excellent mixing; little-to-no cooling effects due to moisture intrusion; proper weather station exposures, etc.!). Regional maximums tend to change “in lockstep,” so-to-speak, based upon temperature changes aloft.

It is worth repeating, because this is the best argument which demonstrates just how improbable the Death Valley 134F temperature in 1913 was: “Maximum temperatures at desert weather stations during hot and dry summer weather are very predictable.” Freaky, unexplainable temperature patterns do not occur in a well-mixed lower troposphere. The atmosphere obeys the laws of physics and plays by the rules. During the hottest week in July 1913, while the closest neighboring stations had maximums some 3-to-8 degrees (F) above normal, maximums at Greenland Ranch were about 11-to-18 degrees above normal. The maximum temperatures in the region not only suggest, but they all but prove, that the associated airmass during the period could not support the high temperatures that were reported at Greenland Ranch in Death Valley. We will investigate this in more detail in other parts. Now let’s take a look at earlier material regarding the high temperature record.

DEATH VALLEY WEATHER STATIONS AND RESEARCH

This section will review some of the early research and material which is pertinent to the 134F report, and the temperature and climate record of Death Valley.

HARRINGTON

The first official weather station to be established in Death Valley operated for only five months, from May through September in 1891. Mark Harrington, the chief of the new U.S. Weather Bureau, set up a first-order station “at the foot of the Funeral Mountains, about two miles northwest of the mouth of Furnace Creek.” An online copy of Harrington’s report (Bulletin No. 1, “Notes on the Climate and Meteorology of Death Valley, California”) is available at google books and is a must-read for anyone looking to become more familiar with summer weather in Death Valley. Hourly wind, temperature, humidity, pressure, sky condition, precipitation and weather observations were taken for these five summer months in 1891. The observer was John H. Clery. (Where are the original observation sheets and charts?! Let’s scan them and put them online!) The maximum temperature that summer was 122F. The assistant observer, R.H. Williams, “succumbed to the heat soon after his arrival” and required treatment in Keeler. In his conclusion, Harrington states: “The air is not stagnant but in unusually active motion” and “it is not only hot in summer, but consistently hot.” And, finally, “The heat and movement of the air together make this a very dry – an arid place – and this aridity in summer is almost as consistent as the heat.”

GREENLAND RANCH AND DEATH VALLEY COOPERATIVE WEATHER STATIONS

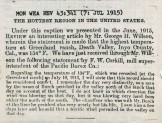

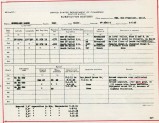

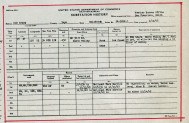

A cooperative weather station was established at Greenland Ranch (later called Furnace Creek Ranch), in Death Valley in June, 1911. This station was open for nearly 50 years, with just a couple of minor moves, at an elevation of about 178 feet below sea level. The observer was the Pacific Coast Borax Company. In the June, 1913, issue of Monthly Weather Review, Alexander McAdie commented on humidity conditions and instrumentation at Greenland Ranch. Two years later, G.H. Willson, a Weather Bureau district forecaster in San Francisco, provided an excellent historical background of the establishment of the station and a review of the first several years of record. Here are scans of these reports in Monthly Weather Review, and a scan of the observer’s official form for Greenland Ranch for July 1913:

The MWR article by Willson is important, as it describes the siting of the Greenland Ranch instrument shelter and discusses the record high maximum temperatures during July 1913. (See Part 6 of this study for a lot more on Greenland Ranch and the weather station history.) Willson notes that Greenland Ranch “embraces about 100 acres of irrigated land” and its thermometer shelter was placed “over an alfalfa sod, the floor about 4 feet above the ground, the shelter door facing north and about 50 feet from the nearest high object. The location is such that the shelter is not exposed to the reflected heat of the desert.” Willson himself emphasized this latter point with italics, and the effect of the siting of the weather station is made clear in his following paragraph: “Evaporation is excessive in this section and liberal irrigation is necessary to maintain plant life; hence, the cooling by evaporation from the surrounding damp ground and live vegetation is probably enough to lower the readings of the instruments several degrees. Undoubtedly the temperature down in the desert bottoms of the valley is much higher than it is at Greenland ranch.”

The Greenland Ranch station closed in April, 1961, and a new Death Valley weather station opened near the new Visitor’s Center, 0.4 miles to the north-northwest. The “Death Valley” thermometer shelter remains in the same spot today, some 120 feet or so north of the visitors center building, at an elevation of -194 feet. The observer is the National Park Service. Here, the ground cover is dry and relatively barren. However, the irrigated lawn of the visitors center and the bulk of the Furnace Creek settlement are south of the station. (2020 Update: the lawn in front of the visitor’s center building was changed back to a more-typical desert surface around 2013.) Winds during the hottest part of the day in summer at Furnace Creek are usually out of the south, and the cooler nature of this environment does have an effect on maximum temperature readings at the current Death Valley weather station site. (2020 Update: the removal of the well-watered lawn means no more cooling and no more cooling effects upon the weather station instrumentation.) During the 1980s, I found that psychrometer spins on sunny summer afternoons showed that locales surrounding Furnace Creek, away from any evaporative cooling effects of irrigation and vegetation (and at a similar elevation), are regularly a degree or so warmer (F) than the area immediately around the Death Valley thermometer shelter. The current Death Valley weather station site is somewhat protected from south winds by the visitors center and the buildings and trees in and around Furnace Creek. It might be that decreased wind movement through the instrument shelter area helps to increase maximum temperatures slightly, given that it is above typical bare ground. Better said: the somewhat wind-protected locale of the thermometer shelter likely mitigates the cooling effects of the vegetation and irrigation upwind. Roof and Callagan noted, in 2002: “As with wind movement, measured evaporation has decreased in recent decades due to growth of trees around Furnace Creek.” (BAMS, “The Climate of Death Valley”) The rising trend in annual maximum temperature at Death Valley in the last 20 to 25 years or so may be due in part to a decrease in wind past the instrument shelter due to heavier vegetation to the south. The parking lot to the east of the shelter may contribute to somewhat higher maximums on occasion. But, the Furnace Creek oasis area in general is cooler than its surroundings on summer afternoons, and it seems likely that Death Valley maximums would average a degree or two warmer if its weather station were moved a mile or so in any direction away from Furnace Creek. The Roof and Callagan article is an important read!

Additional information on the siting and exposure of the Death Valley weather station is here.

Willson (MWR, 1915) shared that the shelter at Greenland Ranch was over alfalfa sod, and that the nearby open-desert-area maximum temperatures would presumably be “much higher.” A photograph of the station appeared in MWR in 1922 (see below—the view is to the west), and the instruments appeared to be above bare ground. The substation history remarks for Greenland Ranch read “Ground exposure over cultivated ground” for the period from 1911 through August 1929. (A photograph of the station in 1926, looking north, appears in Roof and Callagan’s paper on Death Valley climate.) The station was moved 310 feet to the northeast on August 31, 1929, and elevation increased from -178 to -168 feet. The substation history remarks for the period from September 1929 to 1939 state: “Ground exposure, over bare grnd. In 15′ square wire fence enclosure.” In April 1939 the instruments were moved 40 feet to the west because of highway relocation.

The record states that the Greenland Ranch instruments were above cultivated ground, or “alfalfa sod,” from 1911 to 1929, and over bare ground thereafter. Photographs from circa 1920 show the shelter above bare ground with no farmland in the vicinity, but images from about 1916 and 1924 show the shelter above a patch of grass or alfalfa, with a cultivated field just to the west. If the instruments were indeed directly above, or inside of, a cultivated field when Greenland Ranch cooperative weather station was established in 1911, then something changed by about 1920. In Death Valley/Historic Resource Study/A History of Mining (National Park Service, 1981), authors Greene and Latschar state that “During the 1920s the ranch also produced two hundred tons of alfalfa annually that were fed to a herd of high-grade beef cattle that were in turn fed to the men at Ryan.” The alfalfa-growing operations did not stop between 1911 and 1920. What happened to the “cultivated ground” around the shelter? Why is there no evidence of a cultivated field to the west of the shelter in the photograph above? Please see “part 6” of this study for a lot more information and pictures!

The individual charged with reading the weather instruments daily at Greenland Ranch during most of its initial decade of operation was Oscar Denton. The NPS study by Greene and Latschar (referenced above) mentions the early ranch caretakers, including Denton:

“(Ranch watchman and caretaker Jimmy) Dayton served as caretaker and foreman of the ranch for about fifteen years, until his death in 1900. By the early years of the next century one Oscar Denton had taken over his duties, and with the help of local Indians was continuing to raise alfalfa and figs. After the turn of the century, the ranch was the scene of increased activity as dozens of prospectors combed the nearby ranges as part of the new southern Nevada mining boom centering around Tonopah and Rhyolite and their environs. The ranch was the resting place where these “desert rats” could lounge beneath the trees and bathe in the ditches while awaiting supplies ordered to be sent to Denton from Death Valley Junction. This was the place to which everyone went whenever loneliness overcame him and he needed human association and conversation. The old time Death Valley prospectors traveled alone, their burros the only companionship they had. Without Furnace Creek Ranch, Oscar Denton, and the Panamint Indians, Death Valley would have been intolerable.” This quote appears to be from Deep Enough: A Working Stiff in the Western Mine Camps, by Frank A. Crampton. (Note: Dayton’s death was probably in July of 1899.) Also from this book: “It was not often that more than one or two of the old timers, prospectors, or desert rats were at the Furnace Creek Ranch at the same time, but Oscar was a good listener, and he passed the latest stories and the best lies to the next to come for the regular clean-up and supplies.”

In the September 1922 issue of Popular Science Monthly an image of Oscar Denton is provided, with the caption: “Oscar Denton, foreman of the Furnace Creek Ranch for eight years, is the only white man who ever survived a second summer in the blazing heat of the valley.” In the accompanying article “Welcome To The Hottest Spot on Earth!”, we learn a little more about Denton: “Two white foreman met death by daring to spend a second summer at this ranch, and two others, equally courageous, went insane. Only one white man, Oscar Denton, of San Diego, has ever spent more than two summers at Furnace Creek Ranch, and he recently quit — after eight years — to be succeeded by Victoriano Cebellos, a Mexican.”

Denton was the weather observer at Greenland Ranch in July 1913; and, as ranch foreman, was responsible for the alfalfa crop. Perhaps Denton elected to stop cultivating and irrigating the area immediately around the weather station during his tenure. Was alfalfa sod beneath the thermometer shelter in July 1913? I don’t know, but chances are very good that it was, just two years after the station was established. Oscar Denton began signing the Greenland Ranch observation forms in September, 1912. (The forms were signed by Thomas Osborn from June 1911 to June 1912, and by “Wm Meston for Thos. Osborn” in July and August of 1912.) It appears that Denton’s final month as observer at Greenland Ranch was about February, 1921. The summer forms from 1921 through 1927 were signed “Victor Ceballos.”

Let’s get back to the cultivated and irrigated ground cover below and around Greenland Ranch weather station, presumably as late as the summer of 1913. An environment such as this would have had a large impact on temperature inside of the thermometer shelter, just four feet above the surface. The hot and dry environment of Death Valley is responsible for very impressive evaporative cooling effects. When temperatures are as high as 120F and desert dew points are a typically dry 32F (7 percent RH), the wet bulb temperature is only 70F, a full fifty degrees cooler than the dry bulb! If the temperature is 110F and the dew point is a somewhat moist 55F, the wet bulb temperature is 74F, or thirty-six degrees cooler than the ambient temperature. It probably is not a stretch to maintain that the wet bulb depression on nearly all summer afternoons on the floor of Death Valley ranges from about 35 to 55 degrees. On an extremely hot and dry day, with a temperature of 130F and a dew point of 32F (4% RH), the wet bulb temperature is 73F and the wet bulb depression is fifty-seven degrees. Hot and dry winds that move over an irrigated alfalfa field are going to cause quite a bit of evaporation, transpiration, and cooling of the air in contact with moist surfaces. According to the NPS article on the early history of Furnace Creek Ranch:

“The presence of water, shade trees, and grass in the area led to temperatures that usually ranged from eight-to-ten degrees cooler than elsewhere in the valley, and by 1885 the farmstead was rich in alfalfa and hay, while cattle, hogs, and sheep were supplying fresh meat for the tables of the Harmony borax workers.”

The writer’s estimation of “eight to ten degrees cooler” might be overstated a little, but it is not difficult to conceive of parts of the ranch being three-to-six degrees cooler on sunny summer afternoons as compared to its barren surroundings. Some especially shady, moist, grassy areas might be as much as eight-to-ten degrees cooler (at shelter level) during optimal conditions. But how much cooler were the earliest Greenland Ranch weather station maximums compared to the open desert away from the ranch? I suspect that the instrument location above alfalfa sod resulted in summer maximum temperatures some two-to-four degrees cooler than they would have been had the Greenland Ranch thermometer shelter been placed, for instance, a little bit east of the alfalfa fields and above bare, uncultivated ground. It is worth repeating here: Willson (MWR, 1915) suspected that “cooling by evaporation from the surrounding damp ground and live vegetation is probably sufficient to lower the readings of the instruments several degrees.” The original Greenland Ranch shelter location and environment was probably a few degrees cooler on average, perhaps as much as 4 or 5 degrees (F) cooler, than the current (bare ground cover) Death Valley weather station location, just north of the visitor’s center. (2020 Update: I revised the wording a little in the previous sentence to indicate a slightly larger discrepancy in summer maximums between the original GR station and the current DV station. My original wording, from 2013, was “a couple of degrees cooler.” The environment around the current DV shelter has promoted a slight increase in summer maximums in the past decade or two.) The irrigated and cultivated environment around the Greenland Ranch shelter, and associated evaporative cooling, likely had an even greater impact on minimum temperatures. On nights with any lull in the wind, the air cooled around the shelter would be able to linger and cool further, resulting in low temperatures easily five to ten degrees (F) cooler than the surrounding desert, perhaps even quite a bit more than ten degrees cooler. Keep in mind that it is not known exactly just how long the original instrumentation was above the moist sod/alfalfa ground cover and alongside the alfalfa field. The original moist environment promoted very large daily temperature ranges (by Death Valley standards), and the period of very large daily ranges ended during 1913. After 1913, daily ranges were never again as large at GR and DV. The average and extreme daily range data strongly suggest that the instrumentation was above (and/or near) increasingly drier ground cover(s) after 1913.

The relatively “cool” and conservative siting of the Greenland Ranch shelter may be the key factor which led to the record temperature reports by Denton in July 1913. (The full explanation will come later, though!) Why was the station situated in a moist, cultivated area? Back in the first part of the 20th century, it was standard procedure by the U.S. Weather Bureau officials to place cotton-region thermometer shelters above grass (or the typical area ground cover, if it was not bare ground). Even in the Mojave Desert, many, if not most, of the early weather stations were above non-natural, irrigated grassy areas. (Note: my climate professor, Dr. Arnold Court, reported that the thermometer shelter at CAA station Silver Lake Airport, north of Baker, California, was one of the first, if not the first, thermometer shelters to be sited above a bare desert surface. I do not know how he knew this, but Court was active in studying Death Valley weather records and heat events in the 1940s, when nearby Silver Lake AP was in operation. Silver Lake AP had weather observers on hand around the clock for the usual hourly observations and special observations.) The practice of placing shelters above grass at desert stations undoubtedly caused lower maximums and minimums in temperature back in the day!! The “above grass” rule was relaxed into the mid-to-late 20th century. The original thinking back then was that thermometer shelter placement above grass would provide better, more consistent and comparable temperature data and records among all stations. There was likely an eastern United States bias involved here. The country, and the “weather station establishment” began in the east, where moist soils and grassy ground cover were just about everywhere. The cotton-region shelters were good, but not perfect, at providing representative and acceptable ambient temperature data during sunny conditions. The inside of the thermometer shelter tended to heat up a little more than desired when it was placed above bare ground, particularly when beneath bright sunshine during light winds. So, practically all United States weather stations had their thermometer shelters above grass prior to 1940. Again, it was thought that having all shelters above grass would be a good standard and, as Willson put it, would not allow “the reflected heat of the desert” to cause artificially inflated maximum temperatures. There was definitely the notion that having the thermometer shelter above grass was preferred, in order to effectively eliminate the “reflected heat of the desert” buildup around and inside the shelter. But, in very dry regions, the practice was probably ill-advised. The artificial cooling due to irrigated and unnatural surface cover tends to be greater than the slightly inflated hotter maximums when the shelter is above bare ground. The (now) old-style cotton-region shelters were not perfect for high-temperature measurement in desert environments when above bare ground. But, they were not bad, either. Proper exposure and very good ventilation are, or were, very, very important for adequate temperature measurement during bright and sunny afternoons in summer in the desert. If properly sited and above bare ground in the desert, the cotton region shelters might result in maximums that are about 1/2 to 1 1/2 degrees F too warm.

Accurate, reliable, and representative temperature measurement in sunny and very dry environments such as Death Valley has never been easy. Radiation effects can be intense, and the dry air reacts quickly to radiation flux. Standardized thermometer shelters can slowly lose their paint and get warmer. Radiation shields for electronic temperature sensors vary widely in their ability to minimize the affects of direct sunlight. Significant temperature gradients are commonplace from the surface to sensor level both day and night, and sensor height above the ground can be a big factor. Exposure and ventilation are critical for obtaining good data. In desert settings, is it better to site instruments in the open, above typical bare ground? Or is it better to place your thermometer shelter, or radiation shield and sensor, under a shade tree to minimize direct and reflected sunlight? How close is too close to non-native and or irrigated vegetation? How close is too close to nearby buildings? My Masters Thesis closely scrutinized maximum temperature differences at a slew of weather stations in and around the Baker, California, area (in the Eastern Mojave Desert). It was found that summer maximum temperatures are greatly influenced by station exposure and local surface cover. Wind-protected areas above bare ground are routinely several degrees warmer on summer afternoons compared to well-exposed places and stations near springs, grassy and irrigated areas, oases with plenty of shade trees, etc. Temperature differences of this type are much less in areas with higher humidities. At Greenland Ranch, the thermometer shelter was originally placed at a location which was representative of conditions above an irrigated alfalfa field at Furnace Creek Ranch. It was not placed in a spot which was especially representative of its widespread and barren surroundings.

In Willson’s article for the MWR, he reveals that the maximum thermometer at Greenland Ranch was “graduated up to 135F only”, and a note by the observer with the July 1913 report “stated that he doubted if the record was sufficiently high because other ordinary thermometers at the ranch showed a much higher temperature.” Somewhat similarly, from an article by Sean Potter in Weatherwise in July/August 2010:

“Soon after reports of the record temperature began circulating, questions arose as to its validity. Apparently, when Denton sent his monthly weather report to the Weather Bureau, he attached a note saying that he doubted if the record was sufficiently high, since the official Weather Bureau thermometer only went as high as 135°F—one degree above the record—and since other thermometers at the ranch showed a much higher temperature that day.”

Potter’s wording differs a bit from the version by Willson. I am not sure if Potter is putting words in Oscar Denton’s mouth or not, based on Willson’s article. Did Denton write that note to suggest that, because the maximum thermometer only went up to 135F, that an even hotter temperature value would have been realized on July 10, 1913, had the maximum thermometer been graduated up to 140F or 150F? Or did Denton doubt that the record was sufficiently high only based on the other thermometers? Does it matter? If Denton truly believed the reading might have been hotter had the thermometer been graduated higher, then that might say something about Denton’s familiarity, or lack thereof, with the instrumentation. In Court’s “How Hot Is Death Valley” from 1949, the 134F record and Denton’s remarks are closely scrutinized. Court notes: “It is common for thermometers on the walls of buildings, unprotected from the sunshine and ground radiation, to read much higher than instruments properly exposed in shelters. In none of the reports concerning the record temperature is there any indication that the thermometer was subsequently checked or recalibrated.”

Why would Denton write a note such as this and attach it to the monthly report?! This was Denton’s first summer as the weather observer at Greenland Ranch, but some research shows that he likely spent at least parts of a couple of previous summers at the ranch. It seems likely that Denton was accustomed to checking the non-standard and ill-exposed ranch thermometers with the inflated temperatures which Court referenced. Suddenly, as official weather observer now, the 130F or 140F summer afternoon temperatures that he had been accustomed to reading were being undercut substantially by the official Weather Bureau instruments. That’s no fun! That’s not fair! That doesn’t seem right!

Given Oscar Denton’s note, could it be the case that he was not enamored with the low, conservative maximum temperature readings from inside of the thermometer shelter and above the cool alfalfa sod? After all, wouldn’t you prefer to brag to your occasional visitors about surviving a day that got up to 130F versus a day that was “only” 120F? Could it be the case that Denton, unimpressed and annoyed (or displeased or dismayed) with the “low-ish” maximum temperatures from the official instrumentation, strayed from protocol and “cooked the books” in some of his reporting? Does not Denton’s note cast some suspicion upon the record high temperatures in July 1913?! Was the note written in part to somehow justify, at least in Denton’s mind, inappropriately derived maximum temperatures?

Part 6 contains a lot more information on Greenland Ranch and Oscar Denton.

STUDIES BY ARNOLD COURT

Court (in “How Hot Is Death Valley) mentions that “Willson, district forecaster at San Francisco, studied the weather maps without finding any ‘peculiarity that would explain the extremely hot weather in Death Valley in July, 1913.'” Continuing, from Willson (1915): “The weather type was that which always causes high temperatures over the south Pacific coast district, it was not unusually pronounced, and did not give record temperatures in any other portion of California. The wind along the eastern slopes of the Sierra was very light and from the north, causing a slow southward movement of the air from the high plateau and mountain regions of northern Nevada.”

Willson postulated that “the condition was probably local as is often the case in mountainous regions, and the exceptionally high temperatures were confined to Death Valley.” It is doubtful that Willson would agree with his 98-year old assessment if he were alive today. Why has Death Valley failed to reach 130F again, much less 134F? (2020 Update: Death Valley finally hit an authentic 130F maximum on August 16, 2020!) Did this “local condition” only occur in July 1913? Desert heat waves are associated with excellent mixing covering large regions. Authentic local, abnormally very hot temperatures, unsupported by all surrounding stations (and/or unsupported by the temperature of the lower-to-mid levels of the troposphere) simply do not occur. A sound scientific explanation for the 134F maximum on July 10, 1913, has yet to be offered.

Court (“How Hot Is Death Valley,” 1949) showed that a reading of 134F was statistically likely to be reached only once in 650 years, based on the first 37 years of records at Greenland Ranch. He concluded with “it seem(ed) probable that no future official observation will exceed the present high temperature record for North America now held by Death Valley.” Court was on the right track regarding the unusual, unlikely and anomalous nature of the July 1913 maximums. Court said that “since no unusual temperatures were reported elsewhere, the occurrence of very high temperatures in Death Valley in this (minimal) sunspot period must be classed as fortuitous.”

Court speculated that the high readings might be due to a “short-lived bubble in the maximum thermometer or to a blackening of the instrument shelter through exposure.” Later, Court hypothesized that super-heated sand or dust might have come into contact with the thermometer after being swept up from the hot surface by strong winds (see WW, July 2010).

Though there is no evidence for the bubble, blackening, and superheated-sand theories, Court was looking for something which might have resulted in artificially high maximum temperature readings. “There is no indication that the readings as reported are not correct,” wrote Court. But, he was questioning the validity of the data. “The maximum reading of 134F is accepted by the Weather Bureau, even though it is seven degrees higher than the hottest temperature in any of the other 36 years of record.” (Court, How Hot Is Death Valley, 1949)

In Court’s article “Duration of Very Hot Temperatures” (BAMS, 1952)

it was determined that temperature tended to remain close to the afternoon high temperature for several hours. “Maximum temperatures on extremely hot days were found to be of unexpectedly long duration, rather than occurring as a sharp peak or for a relatively short time.” Using thermograph charts from Cow Creek weather station (four miles north of Greenland Ranch, elevation – 152 feet) in July, 1948, Court found that the temperature tends to remain within two degrees of the day’s maximum temperature for about four hours on very hot days, and on normally hot days, also! (This finding is supported by the automatic station data now available online at both Furnace Creek and Stovepipe Wells, though today’s electronic sensors are much more sensitive to temperature changes and show quite a bit more intra-hourly variation than the old-style thermograph records.) On the hottest summer days, the maximum temperature is typically reached around 3 to 4 p.m. PST, and the temperature remains within about two degrees of the maximum from about 1:30 p.m. to 5:30 p.m. PST. See Harrington’s “Bulletin #1, page 50, for the average hourly temperatures in July, 1891 (times given are EST, 75th Meridian Time).

In Court’s “Temperature Extremes in the United States” (The Geographical Review, 1953), the statistical theory of extreme values is incorporated to estimate “the most probable extreme value likely in any given period of time, on the basis of all of the extremes that have been observed.” For Greenland Ranch, Court notes: “Although 134F was recorded there in 1913, detailed study has shown this observation to be questionable; 127F is the highest reliable temperature recorded since observations began in 1911.” According to the statistical theory of extreme values, Court determined that the highest temperature that can be expected at Greenland Ranch during a 100-year period is 130F. That determination has turned out to be spot-on!

OTHER ARTICLES

An article by Andrew Palmer (Monthly Weather Review, 1922), contains a nice image of the Greenland Ranch thermometer shelter (above bare ground), but contains no new information or details regarding the hot maximums during July 1913. The same can be said for Ernest Eklund’s article in MWR/1933, “Some Additional Facts About the Climate of Death Valley, California.” Eklund said that the 134F report “was recognized as the highest authentic natural air temperature that, to that time, had ever been recorded anywhere under approved conditions of equipment and exposure. Higher temperatures had been reported but were never accepted as trustworthy.”

Robinson and Hunt (“Hydrologic Basin Death Valley California,” Geological Survey Professional Paper 494-B, 1966) found that average maximum temperature at Badwater was 2 to 3 degrees (F) warmer in July of 1959 and 1960 compared to Greenland Ranch.

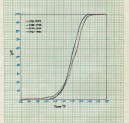

In C.A. Scott’s study “Defining Extreme Desert Environments With Microclimatological Measurements” (1962), hourly observations from Badwater for July days in 1959 to 1961 are graphed:

For more on July temperatures at the Badwater station from 1959 to 1961, see my Master’s Thesis (Reid, 1987), beginning page 210. The Julys of 1959, 1960 and 1961 are among the hottest Julys on record in Death Valley, yet Badwater reached “only” 129F. A temporary Badwater station in 1934 reached 131F, but that report is less than solid, also. (See page 8 here, Stachelski/NWS)

A brief article by David Ludlum in Weatherwise (1963) points out that the “authenticity is doubtful” of both the 136F report from Libya in 1922 and the 136F from Mexico in 1933. And, the 134F at Greenland Ranch “has not escaped questioning as to its reality.” Ludlum does not go into much detail however, with regard to Death Valley’s 134F report.

In Geological Survey Professional Paper 494-B (1966), Hunt, Robinson, Bowles and Washburn provide an excellent overview of Death Valley climate (pages B1 to B11). The record temperature of 134F is not scrutinized, however. I advise reading the climate part anyway!

Lawrence Hein (1980), in an unpublished paper for a college climatology course taught by Dr. Arnold Court at California State University Northridge, focused on the statistical likelihood of Death Valley’s 134F temperature. Hein concluded that the 134F record “should be considered incorrect” in part because it is so much higher than all of the other annual maximums and it is statistically likely to occur only “once in 1396 years.” Hein did not, however, compare conditions at surrounding stations during July 1913 to the reports from Greenland Ranch.

Finally, John W. James, the official State Climatologist for Nevada, writes in the June 1994 issue of Climatological Data for Nevada, with regard to the new record maximum temperature for the state of Nevada (125F at Laughlin) late that month: “At Death Valley N.P., the mercury reached 128F…It was also 128F there in July 1972. The all-time U.S. high of 134F, recorded at Death Valley in July, 1913, is suspect as there has not been a reading above 128F since then. However, the record is still accepted, for lack of knowledge about atmospheric conditions, instruments, and observer techniques 80 years ago.”

Greenland Ranch and Death Valley cooperative weather station documents:

100-YEAR ANNIVERSARY OF 134F REPORT

On July 10, 2013, the National Park Service hosted a “celebration” conference at the Death Valley Visitor’s Center in Furnace Creek. Several presenters spoke about the heat in Death Valley, and some background was provided regarding the record measurement in 1913. This event was held 11 days after Death Valley had a maximum temperature of 129F. A handful of links to articles regarding the 129F record for June and the Death Valley celebration are on my web site. The official NOAA web page announcement for the event is no longer available, but some details are available here.

One of the speakers was Chris Stachelski, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Las Vegas. Stachelski discussed the 134F record and circumstances, and provided a write-up for the Park Service web site.

Stachelski is the author and lead researcher of the Death Valley Climate Book. This is required reading, especially the History of Weather Observations section! During the 1950s there were problems with the reports from Greenland Ranch, as the observer had poor eyesight and switched to a different time of observation without notifying the U.S. Weather Bureau. Later in the decade, the observer gave up taking the observations altogether! There are several excellent photographs of Furnace Creek weather stations past and present, including the Greenland Ranch station in March, 1924. It appears that the thermometer shelter and rain gage are above typical, barren, desert ground cover. But, the station is immediately adjacent to cultivated land. Assuming that the shelter opens towards the north, the vegetated field is on the west side of the weather station. Any wind with a westerly component here would likely be cooled somewhat due to the irrigated vegetation. One image shows two “unidentified individuals” standing by the thermometer shelter. I suspect that the station observer at the time, Victor Ceballos, is the one on the left.

In the “Temperature Record” section of the Death Valley Climate Book, Stachelski notes numerous instances of suspect data in the Greenland Ranch temperature record. These were due to faulty instrumentation and “poor observing practices on the part of observers at the time.” Most of the problem data were with the minimum temperatures, which were sometimes obviously too high and resulted in unrealistically small daily temperature ranges. Stachelski, with the help of the National Climatic Data Center staff, removed some of the suspect data for the Death Valley Climate Book. Some additional questionable data were still being scrutinized. In some instances, temperature data from nearby cooperative weather stations were checked to help fish out the suspect temperature reports at Greenland Ranch.

Towards the end of the book, the 134F record is discussed in a section called “Twelve Significant Weather Events.” The 134F record is the second event listed, and is titled “Hottest Temperature Ever — July 10, 1913.” Stachelski begins by noting that the July 1913 event was “not noted for being a large scale regional heat spell.” Given the problematic data for Greenland Ranch through its period of record, and given that other surrounding stations did not have especially hot weather during the record run at Greenland Ranch, one might think that the next step would be to note that the maximum temperatures during the record hot week at Greenland Ranch in July, 1913, are questionable, and that some climatologists have doubts about the 134F report. Stachelski notes that the minimum on July 10, 1913, was 85F, giving an “incredibly large” daily temperature spread of 49 degrees. (“Incredible means “implausible”, “highly unlikely,” and “doubtful” —- but there is no indication here by Stachelski that the day’s max of 134F and min of 85F are untrustworthy.)

Next comes the important part —- why and how did it get so hot at Greenland Ranch on July 10, 1913? Stachelski says that the lack of upper air data and the sparse weather station network make it “difficult to determine”. A letter from superintendent Corkhill, dated July 6, 1915, is produced, which mentions that the wind was blowing “very hard” on this day. Stachelski contemplates Court’s “superheated wind-blown sand” theory, but does not appear to be convinced. There has been no documentation that blowing sand could cause a spike in temperature on the maximum thermometer in a standard shelter. It is noted that the equipment appeared to be in good working order at the time, and no other explanations are offered. The observer’s note with the July 1913 report (referred by Willson, MWR, 1915) is cited, which questions whether the 134F is even high ENOUGH as the maximum thermometer only went up to 135F and other thermometers around the ranch read much higher. The legitimacy of the 134F temperature record in Death Valley is based on the word and character of the weather observer at Greenland Ranch.

Let’s look again at Fred Corkhill’s letter of July 6, 1915 (on page 6 of the “Twelve Significant Weather Events” section of the Death Valley Climate Book). Corkhill notes that the wind was “blowing hard” on July 10, 1913, and a man died in the valley that day due to the heat, presumably. He spoke with the man’s chauffeur a few days later, and the chauffeur said that there had been a “terrific wind” in the valley that day. The hottest summer afternoons in Death Valley are typically characterized by weaker-than-normal winds. Weak winds allow hot air to build up and linger near the surface and at shelter level. Strong winds are not conducive to local heat build-up and not conducive to strong super-adiabatic lapse rates above the ground. In addition, strong winds are usually not associated with large daily ranges in summer in the desert. (Of course, the wind could have been calm around sunrise on July 10, 1913, which could have allowed a strong inversion right above the moist, cultivated alfalfa field around the shelter and a correspondingly cool-ish minimum. )

A strong afternoon wind through Death Valley on July 10, 1913, implies that mixing in the region was excellent. There must have been a good afternoon dry convection between the surface and much higher levels, likely up to the 700 or even 600 mb levels as is the norm in midsummer. If so, then why weren’t any of the surrounding stations (Independence, Barstow, Jean, Needles, Tonopah, Las Vegas) experiencing exceptionally hot and all-time record-setting maximum temperatures? Maximums were 128F to 131F on six additional days around July 10, 1913, all higher than the second-highest annual maximum of 127F at Greenland Ranch from 1911 to 1960. Why were surrounding stations not showing record or near-record maximums on these other days? Was it windy in Death Valley on these other days? How can one station, Greenland Ranch, have a record week with maximums of 127, 128, 129, 134, 129, 130, 131, and 127F while surrounding stations are not near record levels…yet only reach 127F in the following 47 summers?

In Corkhill’s letter, he states that he “remembers the day very distinctly” (due to the man dying, perhaps), but he does not say that he was at the ranch on July 10, 1913. Apparently Corkhill was not at the ranch on the 10th, as he says in the letter that he “was out to Greenland Ranch on the 11th of July and the temperature then was 129F.” He “does not doubt for a minute that it was 134F the previous day.” There is no indication that Corkhill actually looked at the thermometers inside of the standard weather shelter. The bulk of the letter refers to the Greenland Ranch hygrograph, which is not calibrated correctly, apparently. Corkhill states that he himself is unable to get out to the (borax) mill very often to check the hygrograph for accuracy. He has “tried to show Mr. Denton how to check the machine with a sling psychrometer but it is a little out of his line, and after taking the wet and dry bulb readings he can not figure from the tables the correct readings, and consequently we cannot keep the machine recording as accurately as it should be; in other words, it is not checked often enough.”

Keep in mind that this was written two years after the 134F was reported. Based on Corkhill’s letter, it might be assumed that the Greenland Ranch observer during this period, Oscar Denton, was not scientifically inclined.

WRAP-UP OF PART ONE and SOME CONCLUSIONS AND CONJECTURE

The first part of this study has looked closely at the background and details surrounding the early weather stations and the record 134F temperature in Death Valley. Also discussed was some meteorology, in order to understand how summer weather and temperatures behave in desert areas in and around Death Valley. All of this is prep work for the subsequent parts, which gets into the meat of the data. If you have read all of this up to this point, and if you have read all or most of the links provided, AND read my Masters Thesis, then you should have at least SOME DOUBT as to the credibility of the 130F temperature reports from Greenland Ranch in July 1913.

The amazing week of maximum temperatures at Greenland Ranch in the first half of July, 1913, is amazing only because, I strongly suspect, the weather observer manipulated the maximum temperature reports. The maximum temperature reports are bogus. The air inside of the Greenland Ranch thermometer shelter never came close to 130F, and likely did not exceed 125F or 126F during July 1913. If the temperature had legitimately reached 130 to 134F on three separate days, then at least one surrounding station would have supported the readings. NO STATIONS support the excessive Greenland Ranch maximums of July 1913. There was nothing “unusually pronounced” with regard to the weather pattern during Greenland Ranch’s hot week (according to Willson). It was a typical early July hot spell, with most desert stations running about 3 to 8 degrees (F) above normal. Greenland Ranch maximums were running about 11 to 18 degrees above normal for 8 consecutive days! The air mass which covered Death Valley and the desert areas of California and Nevada was not hot enough to support maximums of 127F to 134F in the Greenland Ranch shelter from July 7th to 14th, 1913.

So, again, what happened? We don’t know — we can only speculate! The only scientifically logical explanation is that the observer, Oscar Denton, did something outside of standard operating procedure which resulted in unusually high maximum temperature entries on the official observer’s form. I suspect that he was not happy with how low the afternoon temperature readings were in the shelter, above the cool alfalfa field, compared to the other (non-standardized and poorly exposed) thermometers in and around the ranch. We do not know very much about Denton, but we do know that he spent summers in near solitude in the relentless blast-furnace-like heat of Death Valley, without air conditioning. There are indications in the literature and in Corkhill’s letter that Denton was not an academic type, and that he might tend to play “fast and loose” with the truth when shooting the breeze with visitors to the ranch. There wasn’t much to do on a typical scorching Death Valley summer afternoon except to watch the thermometer on the wall and to try to keep cool. When it came time to check the high for the day in the shelter, and the maximum thermometer read more than ten degrees lower than what the other ranch thermometers were showing…did Denton fudge the official maximum temperature report upwards some 7-10 degrees? I think so. Another possibility is that Denton moved the official maximum thermometer to a location outside of the standard thermometer shelter for some maximum temperature measurements.

Parts Two and Three will show that Denton was not a good observer, and the maximum temperature record for Greenland Ranch during July, 1913, is not to be trusted.

——-

About the author — me — William Taylor Reid

This is probably a good place to provide a little background on myself. I would hope that you, the reader, are wondering what kind of credentials I carry to the table! I studied Climatology in the Geography Department at California State University, Northridge. I earned a B.A. degree in 1981 and a M.A. degree in 1987. Both of the degrees were degrees in Geography.

The Geography Department at CSUN featured a well-respected climatology curriculum, headed by Dr. Arnold Court. While at CSUN I was a weather observer briefly for the school weather station. Court and the department loaned me a standard weather instrument shelter, hygrothermograph, recording/weighing rain gage, and official NWS max/min thermometers in 1980, which I set up in my backyard in Woodland Hills, CA. The station operated for 18 years, and I was the NWS cooperative observer for Woodland Hills from 1983 to 1997. The shelter and thermometers were basically the same as those used at the stations in Death Valley and all other official United States weather stations for most of the 20th Century. In 1981 I began work on my Masters Degree at CSUN, and I decided to write a Masters Thesis on temperature patterns in the Eastern Mojave Desert. I spent time visiting most of the weather stations in the study area, including Death Valley, and I lived for a couple of weeks at Zzyzx/Desert Studies Center, (south of Baker, CA) where Court and the school had established a standard weather station. For my thesis work, I “reduced” four years of thermograph data from the Zzyzx station.

After receiving my Masters Degree, I worked as hydrologic technician with the Corps of Engineers in Los Angeles, and I worked as a forecaster and climatologist for a private weather company in Los Angeles. Later I worked as a certified weather observer at Los Angeles International AP, Van Nuys AP, Point Mugu Naval Air Station, and San Nicolas Island AP. I have installed automatic (Davis Vantage Pro) weather stations at Chatsworth, Moorpark and Westlake Village here in Southern California, and data from these stations are uploaded to the Internet and the National Weather Service.

I have been taking daily weather observations of some sort from home since 1977, and for much of the 1980s and 1990s I took hourly readings when I could (of temperature, humidity, wind, sky, visibility, rain) in Woodland Hills. I am very familiar with weather stations, old style and new, and with the ASOS stations at airports.

I have been a member of the local and national chapters of the American Meteorological Society for more than 30 years, and I have made several presentations to the local chapter. For more than ten years I was the primary writer for the newsletter of the California Weather Association. I am also a storm chaser and storm photographer. My work at the private weather company and as a storm chaser has helped me become familiar with forecasting and meteorology.

I am basically a weather and climatology numbers junkie —- I own a complete set of California Climatological Data, and I am probably as much of an expert as anyone on the weather and climate of Southern California, the Los Angeles area, and the San Fernando Valley.

So, why have I spent so much time and effort looking into and documenting the early weather records from Death Valley and the 134F report from 1913? I don’t know if I have a really good answer to that. In my Masters Thesis, completed in 1987, I concluded that the 134F report and the other high maximums from July 1913 are about 8 or 9 degrees too high, and very likely resulted from observer error. I was basically just saying the same thing that Court and Hein had stated in their research. This was no great revelation, as far as I was concerned. The Greenland Ranch record temperature of 134F seemed to be WAY too high. My thesis work was the first attempt, as far as I know, to closely compare the July 1913 maximums at Greenland Ranch to the maximums at the closest surrounding stations and to show how anomalous it was. Like everyone else at the time, I had no idea how or why the very high readings came about. Other climatologists thought that the 134F was suspect, but no one was doing anything about it!

In the 10-20 years following the completion of my Masters Thesis, I visited the libraries at CSUN on occasion and pulled out as much of the old Greenland Ranch and Death Valley weather records as I could find, and I copied a lot of the old Climatological Data publications for California and Nevada. I became a lot more familiar with the climatology of hot summer temperatures in the Mojave Desert and Death Valley regions. I compared all-time maximum temperatures and average daily maximums for July at all of the stations in these two regions. I created charts and graphs and did a lot of comparisons of temperature versus elevation. I think that the main point of all of this was to just demonstrate how “OUT THERE” the 134F record was. It was not supported by the GR and DV record, and it was not supported by the data from the other stations that were operating in July, 1913. Someday I could write a professional article on this, and show just how BAD this temperature was!